Reeder’s Movie Reviews: Elvis

Baz Luhrmann has always had a flair for the operatic, sometimes literally so. The Australian writer-director-designer loves to tell stories on a grand scale. The bigger the emotions, the flashier the production values. Romeo and Juliet, Toulouse-Lautrec and the Great Gatsby have all made appearances in his films. Now his spotlight turns to the King of Rock ‘n’ Roll, Elvis Presley. Well, partially, anyway.

This latest manifestation of Luhrmann-style extravagance (his sixth feature as director) does not lack for entertainment value. Even given all of its weaknesses and excesses, it provides a bounty of visual and aural stimulation. Its sheer virtuosity sustains it.

In telling Elvis’ story over three decades, from teenage heartthrob to Vegas lounge act, Luhrmann has it narrated by his subject’s infamous manager, “Colonel” Tom Parker (Tom Hanks). That creates a fundamental imbalance in the picture for most of its 2 hour, 40 minute running time, given Hanks’ wealth of lines and stature as an actor in relation to Austin Butler (Elvis), who exudes charisma but lacks enough meaningful dialogue or emotional depth.

In fact, the movie shares a very specific quality with many operas. Much of the plot development happens in the dynamically staged musical numbers and densely edited visual montages–yes, this story’s definitely “all shook up”–rather than in dialogue-driven scenes.

Luhrmann’s devotion to research does add many grace notes to the picture, not just to the carefully reconstructed Graceland estate. We meet the young Elvis in the early 1950s in Memphis, where the sounds of spirituals, gospel music and R-and-B–the music of Black America–shaped his appreciation for the art form. The physicality of the performers, both in the churches and in the clubs on Beale Street, also left an indelible mark on his own, ultimately revolutionary, style. When he first came to the studios of the legendary Sun Records in 1954, he had to be cautioned not to move so much while recording. Please, Elvis, respect the microphone and the engineers.

Enter the “Colonel,” an illegal Dutch immigrant with a dubious past as a carnival barker and a gift for marketing. Played with a most curious (and not at all authentic) accent by Hanks, Tom Parker elevates Elvis to a bigger label and international success, even as his star client flouts the social and racial barriers of his time.

During the first two segments of the film, when Elvis bursts onto the scene and subsequently becomes a prolific television and movie presence, Luhrmann faithfully stages many iconic moments in Presley’s career. When he exercises dramatic license, it often serves the greater arc of the story, as in interactions with B.B. King and Little Richard. However, in the movie’s final act, Luhrmann elects to use far more archival footage, which, ironically, harkens back to the generally excellent and better-focused 1981 biopic-documentary, This Is Elvis. The closing shots of the two pictures look uncommonly similar.

In recent years, musical biopics have resonated with strong central performances. Rami Malek earned an Academy Award as Freddie Mercury in Bohemian Rhapsody (2018), and Taron Egerton claimed a Golden Globe as Elton John in Rocketman (2019). Importantly, their characters leapt off the screen. They starred in their subjects’ passionate, messy, iconic lives, seizing the narrative.

Austin Butler’s career has taken him from Disney and Nickelodeon shows on TV to notorious murderer Tex Watson in Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in…Hollywood (2019). Here he immerses himself in the title role, singing, playing the guitar and gyrating in that classic Elvis-like way. He also makes the effort to calibrate Elvis’ changing accent and speech patterns at different stages of his life. In fact, the way he physically moves within the frame in many scenes brings to mind Marcello Mastroianni’s memorable turn in Fellini’s masterpiece, 8 ½ (1963). Butler inhabits the space reserved for Elvis in the story, but he has too few meaningful exchanges of dialogue with other characters and delivers too many of those lines with an arch, studied quality. There are notable exceptions, however, as when the aging, drug-diminished star wearily tells his estranged wife, Priscilla, that he’s “out of dreams.” The picture really could use many more moments like that.

A prosthetically-altered Tom Hanks, as “Colonel” Parker (an honorary militia title conferred upon him by the governor of Louisiana), ultimately comes across as the villain of the piece, yet his narration defines the way the story progresses. He, not Elvis, offers most of the perspective, much of it clearly unreliable. In addition, he gets the most substantial monologue of the movie, a cynical discourse on the art and craft of the “snowjob.”

Priscilla Presley, the singer’s former wife and co-founder of Elvis Presley Enterprises, has praised the film, although her character as portrayed by Australian actress Olivia DeJonge barely registers. Two other Aussies, Helen Thomson and Luhrmann regular Richard Roxburgh, play Elvis’ parents, Gladys and Vernon. Their performances are solid, if perfunctory.

In the end, Baz Luhrmann knows how to engage an audience. Elvis looks terrific and proceeds dynamically, with a generous use of cinematic grammar (swooping camera shots, an eye-popping color palette, shifting frame rates and aspect ratios, dense and fluid editing, and an array of Elvis’ hit songs on the soundtrack). The startling crack of gunshots on the soundtrack at the moments of the assassinations of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert Kennedy, Jr. (not otherwise staged) convey the turbulence of the times. And Elvis’ brave, poignant, historic rendering of “Unchained Melody” in Rapid City, South Dakota, on June 21, 1977 (less than two months before his death at age 42) has been meticulously recreated.

Elvis Presley’s career both reflected and challenged the musical, cultural and racial norms of his time. He was more than just an icon. He was a player in a spacious, complicated narrative. Alas, in Baz Luhrmann’s latest exercise in orgiastic (if brilliant) filmmaking, the King’s life ultimately comes across as relatively passive and constrained, even manipulated, by both the manager and the filmmaker.

More Movie Reviews:

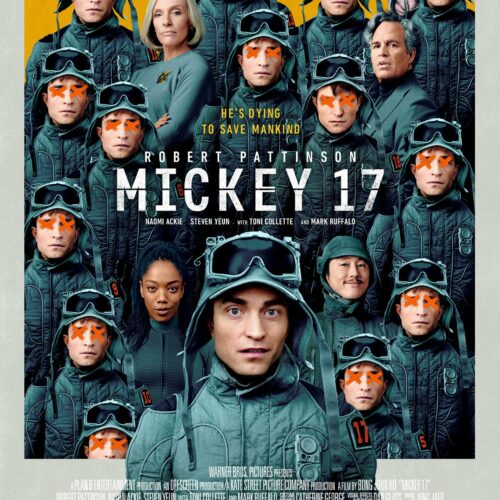

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: Mickey 17

Movie poster of Mickey 17 courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures. Read “You don’t look like you’re printed out. You’re just a person.” In writer-director Bong Joon Ho’s new science fiction

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: A Complete Unknown

In director James Mangold’s new film, Timothée Chalamet portrays the young Bob Dylan (the professional name he adopted at age 21) from 1961-1965. He gives a remarkably nuanced, accomplished performance in a movie that occasionally gets bogged down in truncated or unnecessary scenes, but not too often. The supporting cast shines as well.

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: Nosferatu

A classic tale laced with horrific, religious, folkloric and erotic themes. Robert Eggers seemed destined to make a movie about it. Finally, after a decade of preparation, he has.