Reeder’s Movie Reviews: Men

Sometimes a filmmaker tells a story so dense, so deliberately ambiguous, so deeply rooted in symbolic imagery that you realize you’re either intrigued by and invested in the narrative or you’re utterly defeated by the process. The memory of Men, a hallucinatory study in toxic masculinity, will linger long after the closing credits.

If you’re familiar with either or both of Alex Garland’s previous movies as a director, Ex Machina and Annihilation, then you’ll have a head start on deciphering his latest. Again, he introduces themes of creation and rebirth. The visuals have a painterly precision, and the emotions have a remarkable rawness. He concedes the possibility of baffling or alienating his audience in this case, but he wanted to take a creative risk–a “big swing,” as he puts it.

Irish actress Jessie Buckley (an Academy Award nominee for last year’s The Lost Daughter) plays Harper, a marketing professional grieving the loss of her estranged husband. She decides to escape her familiar surroundings in London for a month’s stay at a country house. Rory Kinnear (Bill Tanner in several James Bond films) portrays the toothy owner, Geoffrey, whose mumbled remarks and leering glances don’t bode well. Neither do the awkward pauses in the conversation. When he tells Harper that she should not have eaten an apple (the “forbidden fruit”) from a tree on the property, you can anticipate the allegories to come.

The plot itself is not really complicated, but the psychology of it is notably so. Harper finds herself trapped–perhaps stalked–in this seemingly idyllic setting. She experiences waves of grief, fear, anger, guilt, regret and defiance. The flashback scenes of her relationship with her husband (Paapa Essiedu) compete with her encounters with various male characters in the present. All the while, Garland offers external manifestations of her inner discomfort.

Much of the tension derives from the men Harper encounters on the grounds of the house and in the nearby village. The landlord and the libidinous vicar seem like classic British parodies, at least on the surface. Add to them a police officer, a less-than-hospitable bartender, a foul-mouthed child and a naked, speechless stranger in the woods (not unlike Adam in the Garden of Eden). To complete this male universe, a leaf-covered Teutonic “Green Man,” whose general appearance harkens back to architectural and pagan/religious imagery of ancient times. The fact that Harper does not overtly recognize the similarity among these characters only adds to the mystery.

Garland’s first draft for Men goes back fifteen years, before he added director to his achievements as a novelist and screenwriter. In his narrative and visual approach to this subject, he brings to mind many established traditions and notable films.

You can see echoes of the pastoral tradition in British horror films, as exemplified by Village of the Damned, Eden Lake and The Wicker Man. More recently, arthouse pictures such as Mother! and Suspiria layered melodramatic elements onto the eco-apocalyptic and Italian “giallo” genres, respectively. However, Men perhaps most strongly suggests the Portuguese film The Ornithologist (2016), a classic essay in cinematic storytelling through a wealth of religious, historical and sexual imagery and symbolism. Like that movie, Men allows its protagonist to realize a form of closure by confronting the truly menacing physical manifestations of her psychological turmoil.

As with his earlier pictures, Garland betrays a keen eye here. Men often glows with beautiful, burnished shades of red and orange, alternating with earth tones and vibrant green. The chant-like music heightens the atmosphere of dread, and at one point seems to track a certain two-word, expletive-deleted phrase in the dialogue.

The actors are excellent. Their line reading is precise and suitably enigmatic. Jessie Buckley conveys the full range of Harper’s emotional state. Rory Kinnear, one of Britain’s finest stage actors, gives an effectively nuanced–and brave–performance.

Men is not a casual entertainment. It demands the viewer’s attention to detail and, even then, doesn’t reveal all of its secrets, or all of its writer-director’s intentions. In Garland’s words, “I wanted to write a horror movie about a sense of horror.” No matter how you feel about his storytelling method here, the bravura climax will not leave you indifferent. Men will never look quite the same.

More Movie Reviews:

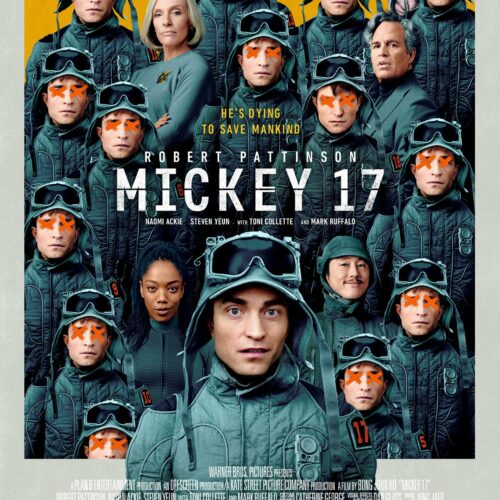

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: Mickey 17

Movie poster of Mickey 17 courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures. Read “You don’t look like you’re printed out. You’re just a person.” In writer-director Bong Joon Ho’s new science fiction

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: A Complete Unknown

In director James Mangold’s new film, Timothée Chalamet portrays the young Bob Dylan (the professional name he adopted at age 21) from 1961-1965. He gives a remarkably nuanced, accomplished performance in a movie that occasionally gets bogged down in truncated or unnecessary scenes, but not too often. The supporting cast shines as well.

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: Nosferatu

A classic tale laced with horrific, religious, folkloric and erotic themes. Robert Eggers seemed destined to make a movie about it. Finally, after a decade of preparation, he has.