Reeder’s Movie Reviews: The Northman

Robert Eggers has only made three feature-length films so far. Even as a modest body of work, they reveal a wealth of obsession and talent.

He burst onto the scene in 2015 with The Witch, a disturbing story about a family in seventeenth-century Puritan New England confronted by sorcery and the black arts. It made Anya Taylor-Joy a star.

He followed that with a harrowing, claustrophobic and altogether virtuosic two-man character study, The Lighthouse (2019). It elicited mesmerizing performances from Willem Dafoe and Robert Pattinson, who speak the language of late nineteenth-century Yankee sailors in all of its ebb-and-flow musicality.

Eggers has now returned with another bluntly-titled movie, The Northman. If the two previous films suggested chamber music, then this latest narrative plays out like grand opera.

A seriously bulked-up Alexander Skarsgård, the Swedish-American actor whose résumé includes stellar work in True Blood and Big Little Lies, heads a formidable cast in a story of bloody revenge set in the Viking world of the tenth-century. As a boy, Prince Amleth saw his father, King Aurvandil (Ethan Hawke) murdered by his uncle, who lusts after power and his fickle sister-in-law, Queen Gudrun (Nicole Kidman). Taylor-Joy appears as Olga of the Birch Forest, a young Slavic woman whose village has been plundered by the Viking hordes. She and the adult Amleth, who has matured into a “beast cloaked in manflesh,” make love and make common cause against the royal usurper and personification of evil, Fjoelnir the Brotherless (Claes Bang). Along the way, they get encouragement from the blind Seeress portrayed by Björk, the legendary singer-songwriter who won the Best Actress award at the Cannes Festival in 2001 for her performance in Dancer in the Dark.

With ingredients like those, The Northman could easily have foundered in lurid mediocrity in the way of the mostly regrettable Kirk Douglas and Tony Curtis epic, The VIkings (1958). But Eggers has larger ambitions and the discipline to realize them. He and his team spent a full year in pre-production, working with historians and experimental archaeologists to bring as much authenticity as possible to the project. The swords, the longboats, the clothing, the huts, the interior spaces. All reinforce this visceral period piece.

You have to admire the detailed approach to language, too. Just like his earlier films, The Northman demonstrates Eggers’ fascination with the sound of the spoken word. Even though the characters here speak English most of the time, it’s inflected in the way of ancient Norse epics, which the director adapted in collaboration with the acclaimed Icelandic poet and novelist Sjón.

As a result, The Northman is brimming with cultural, historical and artistic references. You can start with Richard Wagner’s operatic Ring cycle, whose story derives from Nordic and Celtic legends. Think William Shakespeare’s Hamlet as well. (Prince Amleth, get it.) No doubt about it: something is definitely rotten in this state of Denmark.

As befits this brooding epic, most of its action takes place in darkness or demi-light. Shot mostly on location in Northern Ireland, its vivid imagery includes a floating tree hung with bodies, a Valhalla-like vortex of light, naked warriors with their frightening weaponry enacting a no-holds-barred duel to the death amidst flaming lava, and a group of well-trained ravens straight from the pages of Edgar Allan Poe pecking the protagonist free of the ropes that bind him. Given the dearth of daylight in this film, the sight of sunflowers in one scene may seem positively dazzling.

The battle scenes have their own distinctive character here, too. Eggers, much in the way of Sam Mendes in his epic war film 1917, forgoes the often chaotic look of multi-camera shots for extended, single-camera sequences. They clarify the perspective and intensify the action, with characters entering and departing the frame.

As you might expect of a filmmaker so committed to “historical recreation” (his phrase), the music does much more than just fill the gaps in the sound design. Composers Robin Carolan and Sebastian Gainsborough, who often create material for the British club scene, consulted ethnomusicologists and produced a score which includes historical instruments such as the lyre-like tagelharpa and the zither-like langspil. With the addition of string and percussion ensembles and a choir, you have a cinematic tale “smothered in music,” as Carolan puts it.

When you watch The Northman, you see a movie brimming with mud, blood and gore. The work of a meticulous filmmaker, who averages 15 takes per scene. A picture that harkens back to the French New Wave’s 60-year-old idea of “auteur.” After a decade as a production designer and just three full-length features, Robert Eggers has now established himself as a singular talent of remarkable clarity and vision. Let’s hope that ever-larger budgets don’t blunt his creativity.

More Movie Reviews:

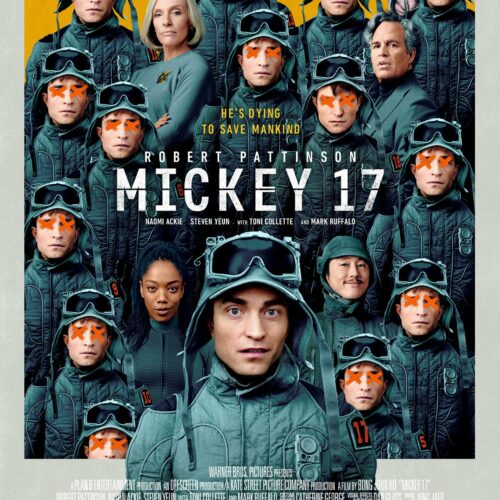

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: Mickey 17

Movie poster of Mickey 17 courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures. Read “You don’t look like you’re printed out. You’re just a person.” In writer-director Bong Joon Ho’s new science fiction

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: A Complete Unknown

In director James Mangold’s new film, Timothée Chalamet portrays the young Bob Dylan (the professional name he adopted at age 21) from 1961-1965. He gives a remarkably nuanced, accomplished performance in a movie that occasionally gets bogged down in truncated or unnecessary scenes, but not too often. The supporting cast shines as well.

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: Nosferatu

A classic tale laced with horrific, religious, folkloric and erotic themes. Robert Eggers seemed destined to make a movie about it. Finally, after a decade of preparation, he has.