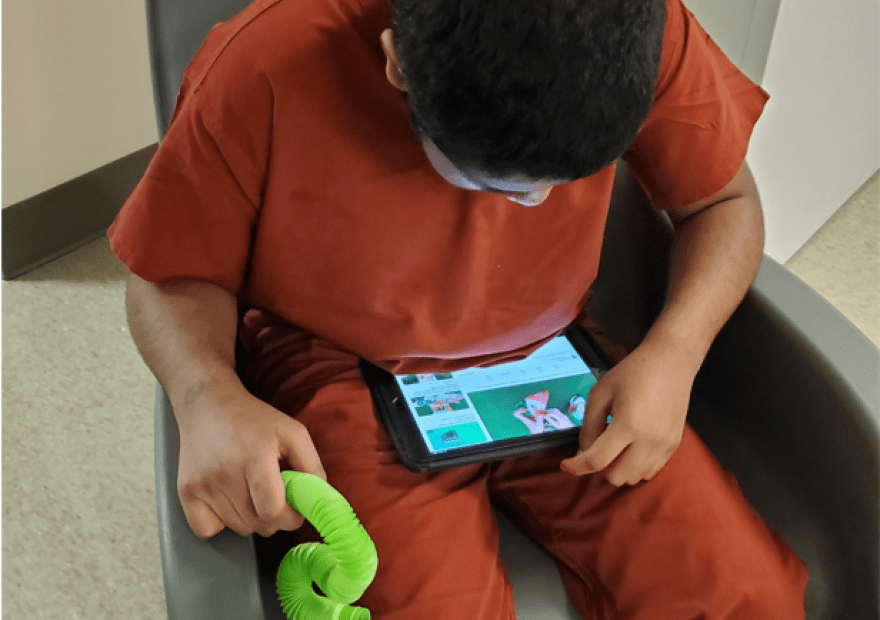

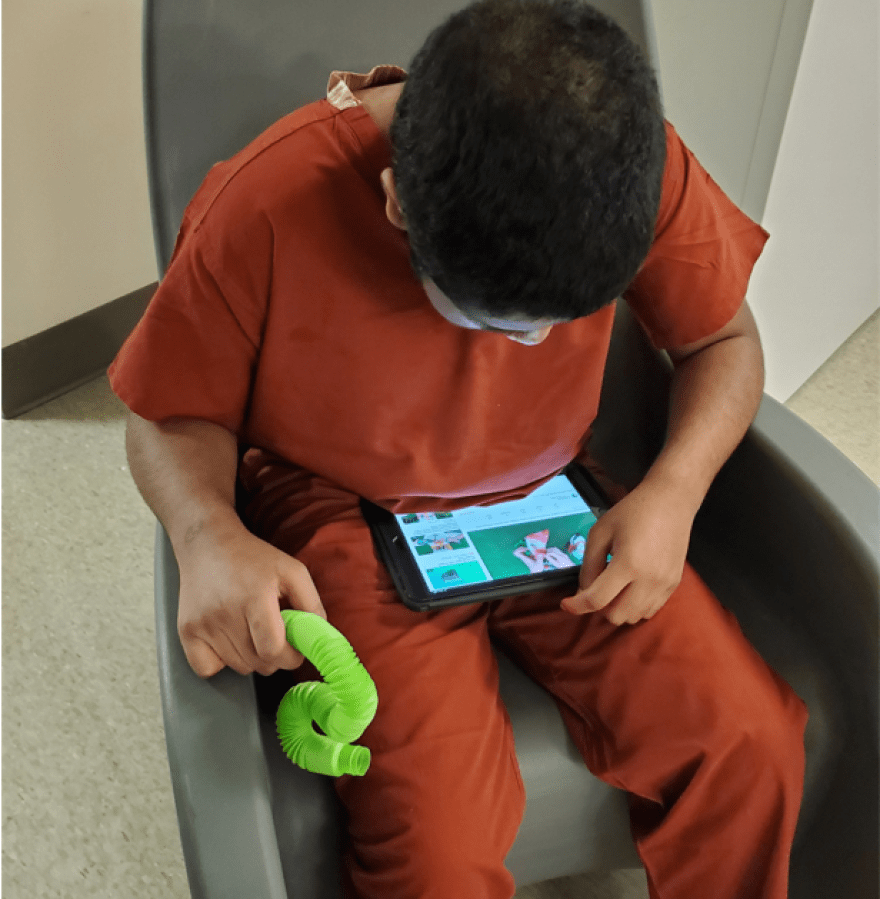

For more than five months, Matthew, a nonverbal teenager with autism, lived in a hospital room at Providence Regional Medical Center in Everett.

He spent Thanksgiving and Christmas there. He celebrated his 14th birthday there. He also gained over 60 pounds there, according to his mother, raising concerns about his blood pressure and cholesterol.

Matthew didn’t have a medical reason for being in the hospital. Instead, he ended up at Providence Everett after he attacked staff at his group home. His mother, who said Matthew acts out when he gets frustrated, felt she couldn’t safely care for him at home. And the group home wouldn’t take him back. With no other options, Matthew remained stuck in the hospital — until earlier this month.

That’s when he was flown aboard a medical transport plane to South Carolina. His mother and younger brother followed on a commercial flight.

Their destination was Springbrook Behavioral Health, a residential treatment facility that specializes in treating complex behaviors that are associated with autism.

The family’s journey across the country represented both a victory and a defeat for Matthew’s mother.

On the one hand, Matthew was finally out of the hospital where he’d been cooped up for more than 150 days.

On the other hand, he was now going to be living on the opposite side of the country without the support of his family and with no one to visit him.

“It’s absolutely devastating,” his mother said recently after returning to Washington from South Carolina.

The public radio Northwest News Network agreed to not identify his mother and use only Matthew’s first name because of his age and to protect the family’s request for privacy.

Disability advocates say Matthew’s story is an increasingly common one and highlights a lack of support services in Washington for youth with autism who display destructive or dangerous behaviors. Many of these cases follow a familiar pattern. Parents reach a breaking point where they decide they can no longer safely care for their child at home. Or a group home decides it can’t manage a particular child’s behaviors. With nowhere else to go, the youth winds up in the hospital. From there, the options are limited: return home, find another out-of-home placement or petition the local school system to pay for an out-of-state boarding school that specializes in serving autistic youth.

In Matthew’s case, there was talk of moving him to a new therapeutic group home in Spokane. But that fell through. His advocates also explored having the school district pay for an out-of-state boarding school that specializes in serving youth with autism. But that too was a no-go. Eventually the team working on Matthew’s case agreed he needed specialty behavioral health treatment. That’s when Medicaid agreed to pay for his placement at Springbrook.

“Matthew’s story just really puts it right up into the forefront that there’s not a safety net for these kids,” said Rachel Nemhauser, with The Arc of King County who worked with Matthew and his family.

That’s a refrain echoed by a constellation of advocates, families and hospitals — including Providence Everett where Matthew was housed.

“While we cannot comment on specific patients, across our state there are increasing numbers of pediatric patients with behavioral health and/or developmental disabilities with behavioral challenges who need care and treatment in specialized centers that can meet their complex needs,” a Providence spokesperson wrote in a statement.

The statement went on to say that hospitals and emergency rooms have become the default backstop because there aren’t adequate placement options.

The governor’s office and legislators say they’re working to address the crisis. In response to a request from the Northwest News Network, Gov. Jay Inslee’s office and the Senate Democratic Caucus separately provided lists of nearly two dozen examples of new spending and programs to address the needs of Washington children in crisis, including youth like Matthew.

They include more than doubling the number of community-based long-term psychiatric inpatient beds for youth by 2024, expanding access to intensive outpatient treatment services and providing greater access to in-home supports. The state also notes it’s increasing the rates paid to service providers and working to beef up case management.

“Our hearts continue to go out to these families,” Inslee’s office said in a statement. “We believe the Legislature’s investment in therapeutic beds and related programs will make a big impact.”

State Sen. Christine Rolfes, a Bainbridge Island Democrat who chairs the Senate budget committee, offered a similar assessment.

“We’re making progress. This is on the Legislature’s radar. But there’s still a lot to do,” Rolfes said.

Ideally, Rolfes said, families would get the help they need before their children end up in crisis and are hospitalized.

Some advocates, though, are more wary. Stacy Dym is executive director of The Arc of Washington State, which advocates for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. In an email, she called Matthew’s long wait in the hospital “unconscionable” and said Washington needs a more robust crisis stabilization system along with long-term enhanced behavioral residential support for children and adults with developmental disabilities.

“We made some small steps forward during the legislative session,” Dym said. “But still no strong commitment to design programs and responses that provide a full continuum of care for children and youth with developmental disabilities in crisis and who may need long-term behavioral care.”

The current gap in services — and the plight of youth stuck in the hospital — recently prompted Disability Rights Washington to file a lawsuit against the state of Washington on behalf of an 18-year-old who’s been ready to discharge from Seattle Children’s Hospital since last August.

The lawsuit against the Health Care Authority (HCA) and one of its Medicaid managed care insurance providers alleges the young man “has been denied a safe discharge plan and has been warehoused on a locked unit at Seattle Children’s Hospital for the last seven months.”

Susan Kas, an attorney with Disability Rights Washington who filed the lawsuit, said that she has found several examples of young people not getting the in-home and community-based services they need to safely leave the hospital and return home.

“This is indeed a devastating situation for the youth and their families, but could be avoided if the state provided intensive behavior supports,” Kas said in an email.

HCA said it couldn’t speak to the specifics of the case because of the active litigation. But in a statement the agency said, “HCA and our partners are committed to providing the services and supports Washington families need, using the significant investments made by the Legislature over the past few years.”

Even as the state ramps up efforts to build a more robust community-based system of care, there are ongoing hurdles. For instance, in-home services were largely curtailed during the height of the pandemic and now, as with many sectors of the economy, behavioral health providers are contending with workforce shortages.

That has families looking for solutions they might not have previously considered — like out-of-state placements. In Matthew’s case, his mother agreed to send him to Springbrook when it emerged as the only option to get him out of the hospital.

Now, she’s adjusting to being 2,700 hundred miles away from her son. She said families who live closer to Springbrook can visit up to twice a week.

“I so wish I could do that,” she said. “What I’m doing is a Zoom call every Friday and Matthew only lasts about five minutes on a Zoom call.”

She’s been told Matthew will likely remain at Springbrook for the next three to eight months. What happens after that is unclear.

“Are they just going to dump him off here? I can’t have that happen,” she said.

She’s adamant that bringing Matthew home is not a viable option given his past behaviors, which she said included attacking joggers, causing a car accident by running into the street and giving her and his younger brother concussions.

“What I want is a situation where it’s kind of settled [and] he’s got a place to live,” she said.