Here’s Something Depressing For The Holidays: States Set New Record For Total Annual Deaths In 2021

Read

The year 2021 isn’t even over, yet Oregon and Washington have already smashed their previous records for total annual deaths. Those records were just set last year. The coronavirus pandemic is only one piece of the explanation.

In 2020, the Washington State Department of Health tallied a record high of 63,180 resident deaths from all causes. The Grim Reaper has already claimed more than that this year – 65,100 deaths as of December 22, according to an agency spokeswoman. When the tally for 2021 is checked and finalized months into next year, the bottom line will probably land between 67,000 to 68,000.

Oregon recorded 40,226 resident deaths in 2020 and is on track to bid a final farewell to 44,000 to 45,000 residents in 2021, according to preliminary Oregon Health Authority data.

While those are depressing numbers, the fatal COVID cases only account for about half of the excess deaths for the year, according to the Oregon Health Authority’s data dashboard. Washington’s percentage is closer to two-thirds.

DOH tallied 3,736 COVID deaths in Washington in 2020. When 2021 ends in a few days, Washington will probably record about 6,215 annual COVID deaths. OHA determined 1,436 Oregonians died of COVID in 2020. That figure is on track to more than double this year to an estimated 4,230 annual COVID deaths, even though vaccines have been widely available for adults since the spring.

So, what is causing the thousands of other deaths above what epidemiologists would typically expect in the Pacific Northwest?

Some of the factors behind the non-COVID surge in mortality have relatively clear cause-and-effect – last summer’s record heat wave, for example, or the rise in drug overdoses. Other explanations have plausibility, but are more difficult for researchers to pin down, such as a possible undercount of COVID deaths or the consequences of delayed health care coming home to roost.

Local and national public health experts have suspected for more than a year that a potentially significant number of COVID-related deaths are not being attributed as such on death certificates.

“Some reasons that reported deaths may be underestimates include that persons who die from COVID-19 might not seek medical care, or might seek care when the virus is no longer detectable, or those who do seek care might not be tested for (coronavirus) infection,” wrote a group of researchers affiliated with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in a paper published this past summer in the medical journal The Lancet.

Fatal drug overdoses started rising before the pandemic and kept going up during 2021. University of Washington addiction expert Caleb Banta-Green described the deadly consequences of the synthetic opioid fentanyl displacing heroin as “stunning,” in a news release. The head of the Northwest region of the Drug Enforcement Administration also did not mince words in laying blame on fentanyl.

“The availability and seizure of fentanyl-laced counterfeit pills has exploded in the region,” DEA Special Agent in Charge Frank Tarentino III said in a statement earlier this month. “Criminal drug networks in Mexico are mass-producing fentanyl which is driving the increase in overdose deaths.”

Death rates have ticked up over the past year and a half for cancer, heart disease and an assortment of other conditions, which could be an indirect impact of the pandemic. It could be collateral damage caused by such things as patients being fearful of visiting their doctor lest they be exposed to the coronavirus or overburdened hospitals postponing procedures.

“The whole issue of the impact of delayed care from the pandemic is an incredibly important one, but also a very difficult one to quantify,” said Dr. Tao Kwan-Gett, chief science officer for the Washington Department of Health. “We’ll need to look at the data long and hard to really assess.”

Health officials this week urged people made cautious by the arrival of the fast-spreading omicron variant to call their doctor’s office or explore virtual care options.

“Anytime you have a variant or some other news that comes out, people start to ask the question, ‘Do I want to go into the health system right now,’” Washington State Secretary of Health Dr. Umair Shah acknowledged during a televised briefing Tuesday.

“If you’re not sure if it’s urgent, or emergent, or an emergency, ask. At least make contact,” counseled Shah. “We do not want people to delay care.”

One statistic from the Washington State Health Care Authority, which oversees coverage provided to low-income residents through the Medicaid program, is revealing. Providers billed Medicaid for 6% less in services in the first quarter of 2021 compared to the mostly pre-pandemic first quarter of 2020. Given that the Medicaid population stayed stable around 1.7 million people, even a single-digit percentage usage drop represents a large amount of health care not received.

A rise in homicides contributed to a small degree to the overall surge in death regionally and nationally this year. In October, Portland broke its previous record for homicides in a year, a record that had stood since 1987. The homicide tally has since grown after a couple more shootings to 73, according to the Portland Police Bureau. For King County, Washington (which includes Seattle), homicides as of early December were running a bit behind 2020, but significantly elevated over prior years.

It’s not all bad news when looking over causes of mortality in the past year. A Washington State Department of Health spokeswoman pointed out that while the book is not closed yet on 2021, deaths from the flu are way down. Last winter’s flu season was remarkably mild, perhaps an ancillary benefit of COVID precautions such as masking and frequent hand washing.

Washington health departments and the Oregon Health Authority also closely monitor trends in suicides. Neither has detected an overall increase in suicide during the pandemic.

As 2022 begins, medical professionals are getting more tools to prevent deaths from COVID. In recent days, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration granted emergency use approval to two antiviral drugs that have the ability to head off severe COVID if taken soon after a patient is diagnosed. Pfizer’s drug Paxlovid showed promise to keep patients out of hospitals. Early studies on a competing drug from Merck named Molnupiravir were not quite as promising. But given the high demand for an at-home treatment and limited initial supplies of the pills, the FDA chose to approve both.

Related Stories:

COVID-19, 5 years later: Reflections on the scars we carry, and resilience in unprecedented times

NWPB caught up with local residents and doctors to talk about how they’ve moved forward following the COVID-19 pandemic. They spoke about how the experience changed them and wisdom they’ve gleaned along the way. These are their reflections.

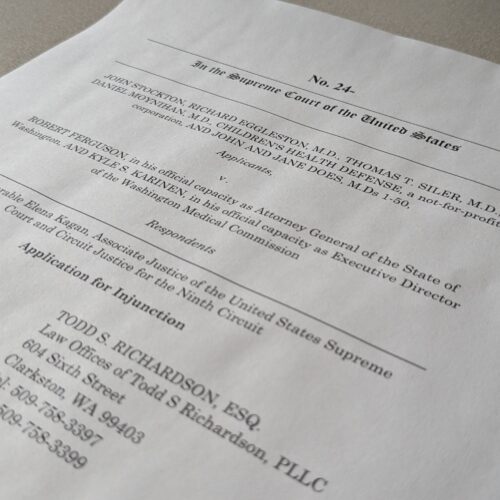

US Supreme Court will consider petition for stay in COVID-19 free speech case

The U.S. Supreme Court will review an application for a stay in a federal lawsuit involving local retired eye doctor Richard Eggleston.

Group representing retired Clarkston ophthalmologist asks US Supreme Court for injunctive relief

A retired Clarkston eye doctor is part of a group asking the U-S Supreme Court to grant an injunction in a lawsuit against Washington state officials.