It’s a race against winter to load heavy pallets of squash on the 1,500-acre Inaba farm.

Four generations of his family has farmed this land, but now Lon Inaba and his family are selling it – not to just anyone. They’re selling it back to the Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation.

“The tribal people have been really good to my family and the Japanese community for the last 75 to 80 years when they started coming,” Inaba says. “And this is a way for us to return the favor.”

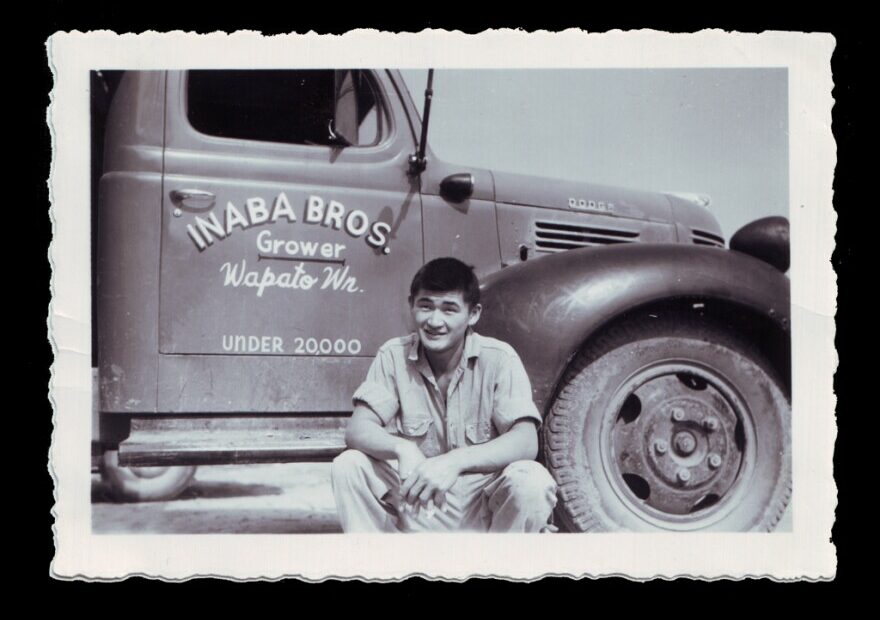

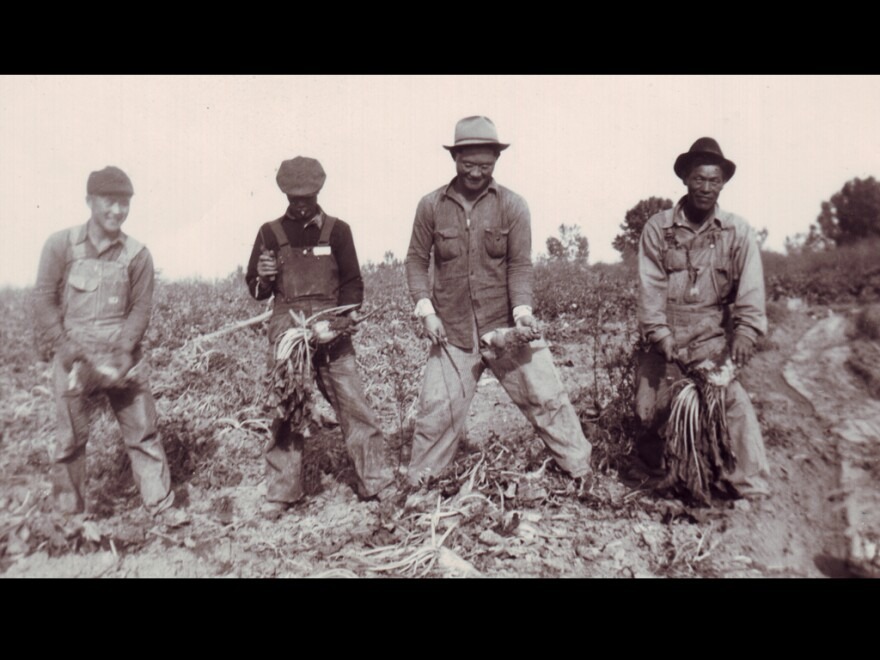

Lon Inaba’s father Ken, his brother Kay, Sheane, and Lon Inaba’s grandfather Shukichi topping sugar beets in south-eastern Idaho after they were recruited to leave the internment camps and work on neighboring farms to bring the harvest in. CREDIT: The Inaba Family

Undesirable alien

Inaba’s grandfather, Shukichi Inaba, got a degree in agriculture in Japan, then came to the U.S. in 1907. But as a person of Asian descent – considered an undesirable alien by the U.S. government – he couldn’t become a citizen or own land. The way he got around this was to lease land on the Yakama Reservation.

“They were able to subsist,” grandson Lon Inaba explains.

Shukichi Inaba and his brother, Tomoji, used teams of horses and manual labor to clear 120 acres of leased tribal land, transforming it from sagebrush to cropland, and helping to construct the irrigation delivery systems, a Yakama Nation press release says. Today, Inaba Produce Farms grows more than 20 different produce crops – many farmed organically – within the Yakama Reservation.

But after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, the U.S. government forcibly removed west coast Japanese people and people of Japanese descent from their land and businesses and interned them in camps.

After a brief stay at livestock exhibition yard in Portland, Oregon, the Inabas were sent to Heart Mountain, Wyoming.

The family grew food there too with many other imprisoned families.

“They did so well, they started shipping the food to the other relocation centers as well,” Inaba says. “And they did so well, that the people in the communities complained that the Japanese people were eating better than they were.”

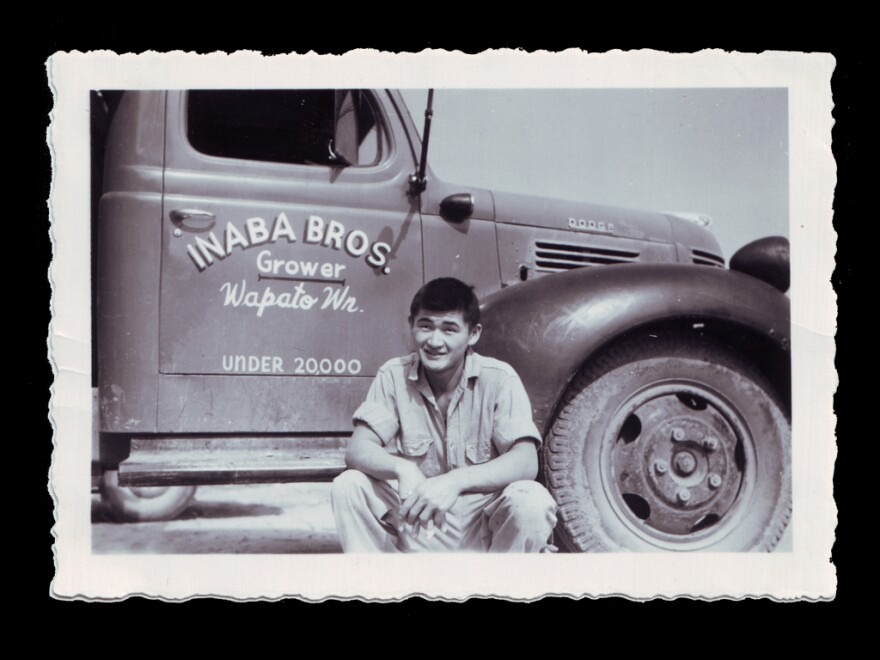

Lon Inaba in his family farm’s greenhouse full of cabbage seedlings. CREDIT: The Inaba Family

Return to Wapato

After the war, the Inabas returned to the land they’d been farming. The laws changed and in 1954, the Inabas bought property within the Yakama Nation that came with water rights.

Now, Lon Inaba is getting ready to retire and the Yakama Nation is starting to take over.

Virgil Lewis is the vice-chairman of the Yakama Nation Tribal Council. He remembers when his grandmother would put food away.

“As a kid, I used to watch my grandmother do that,” Lewis says. “She would can all kinds of fruits, all kinds of vegetables. And she would have a big huge cellar to where all this food was stored.”

Lewis says farming the Inaba’s land would help restore the self-sufficiency the tribes used to have in the era before Safeway and McDonalds.

“With the crops that are being grown here, our people could put that food away,” he says. “To supplement whatever food they’ve put away from the mountains, the deer, the elk, the berries. …Get our younger people to understand that if you get your foods, put them away and store it and save it for the hard times in life.”

Virgil Lewis and Lon Inaba on the Inaba Family Farm this winter. CREDIT: Anna King

‘Part of that bounty’

For Lewis, and for the Yakama Nation’s Phil Rigdon – who will help oversee the new farming venture – this farm means food sovereignty.

Across the nation, Native American communities are prioritizing ‘food sovereignty’ initiatives to support food security for their members, and to promote healthy eating, economic and employment opportunities, and the preservation of cultural and natural resources, a Yakama Nation press release says.

“Our grandparents and great grandparents they could never make it farming,” Rigdon says.

When Rigdon was a boy, he moved the irrigation hand-lines on his family’s two, 80-acre farming allotments.

He says tribal people were only able to grow lower-profit crops like alfalfa and corn silage.

“And you see these apples, cherries, hops all these high economic crops surrounding us,” Rigdon says. “And our goal, is how do we create it so that we create an economy that we could have a part of that bounty, that we can gain the benefit. And I think this is the first step.”

The tribes’ big vision is to trade its produce to help other tribes get food sovereignty too.

And they’ve asked Lon Inaba to stay and teach the next generation how to run the farm.

“My family’s proud, and I know my dad would be proud, so I don’t want to walk away,” Inaba says.

The Yakama Nation sees Inaba as an adopted part of their family – and Inaba sees them as family too.

“We owe a lot to the tribal people,” Inaba says, choking up a bit. “And this is a way to return it.”