These NYC Kids Have Written The History Of An Overlooked Black Female Composer

Listen

Read

By Anastasia Tsioulcas

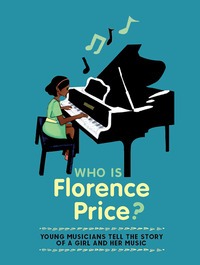

For decades, it was almost impossible to hear a piece of music written by Florence Price. Price was a Black, female composer who died in 1953. But a group of New York City middle school students had the opportunity to quite literally write Florence Price’s history. Their book, titled Who Is Florence Price?, is now out and available in stores.

Who Is Florence Price?, by students of the Special Music School at Kaufman Music Center, NYC. CREDIT: Schirmer Trade Books

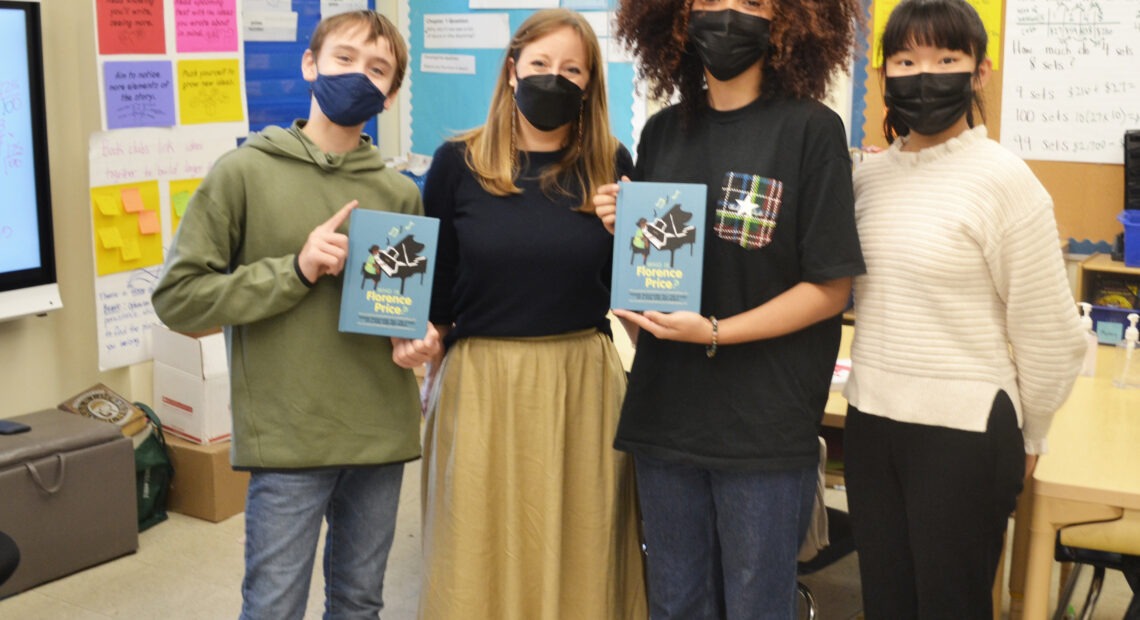

The kids attend Special Music School, a K-12 public school in Manhattan that teaches high-level music instruction alongside academics. Shannon Potts is an English teacher there.

“Our children are musicians, so whether or not we intentionally draw it together, they bring music into the classroom every day in the most delightful ways,” Potts says. “So if you’re talking about themes and poetry, immediately a child will qualify it with the way that a theme repeats in music.”

Potts assigned her sixth, seventh and eighth grade students to study Florence Price — a composer born in Little Rock, Arkansas in 1887. She was the first Black woman to have her music played by a major American orchestra: the Chicago Symphony Orchestra performed her Symphony No. 1 in 1933 and her Piano Concerto in One Movement the next year. In 1939, at her famed Lincoln Memorial concert, the contralto Marian Anderson included Price’s arrangement of the spiritual “My Soul Is Anchored in the Lord.”

Despite Price’s talent and drive, most classical music performers and gatekeepers put her aside, and her work failed to gain traction with the large, almost exclusively white institutions that could have catapulted her to mainstream renown. As she herself wrote in a letter to famed conductor Serge Koussevitzky, “I have two handicaps — those of sex and race.” She was not wrong.

“In 2009, a couple bought an old house outside of Chicago. in the attic, they found boxes filled with yellowed sheets of music. Every piece was written by the same woman, Florence Price. ‘Who is Florence Price?’ they wondered… Florence’s mind was filled with music, but she had a big question. She was a girl and her skin was a different color than so many of the composers she knew about. Could she grow up to be a famous composer, too? When Florence was only 11, her first piece was published. Was it possible that Florence’s music could change things?”

Special Music School is a partnership between the New York City Board of Education and a performing arts center called the Kaufman Music Center, whose executive director is Kate Sheeran. Sheeran was extremely enthusiastic about the students’ work.

“This beautiful book emerged that they wrote together, 45 of them together,” Sheeran recalls. “I found out about it when they brought it down to my office, and I was just floored.”

Sheeran was so impressed that she ordered a small, self-published print run of their work. She sent it around to various people in the classical music community — including Robert Thompson, the president of G. Schirmer, the company that publishes Florence Price’s music.

“I think it’s one of the few moments in my job where I had to cancel the next meeting and I was just kind of filled with tears,” Thompson recalls. “It was just an incredibly beautiful moment.” Thompson agreed to publish the book; all royalties will go to Kaufman Music Center, which is a non-profit organization.

Rebecca Beato is a 14-year-old violinist from Queens. She was also one of the lead illustrators of Who Is Florence Price? and she says that Price has been a personal inspiration. “Her music has been out there, performed by major orchestras,” Beato says, “and she’s a woman of color, which even now — it’s like difficult to get your music shown to the world.”

Writing the book was a process of discovery, says Cobie Buckmire, a 13-year-old pianist from Brooklyn. “I didn’t even know who she was before I started this,” he notes. “All the other famous composers are white men like Mozart, Beethoven, Bach.”

Hazel Peebles, a 13-year-old violist from Harlem, says that you can hear Price’s personal history in her music. “It really is beautiful,” Peebles observes. “She worked in some of her history, some of her Black background into the music. I really just love that and appreciate that.”

What the students learned in creating this book goes far beyond music, Kate Sheeran says. “They’re also seeing that they can have a voice in shaping who writes history and who tells stories,” she says, “and that we don’t have to just accept the way music is presented to us or the way music history is presented to us — that they too can shape that. And that, to me, is the most exciting thing.”

“We talk about representation in literature all the time,” Potts observes. “For kids to be able to become authors and activists in a way, to disrupt the story of the way that classical music is being told. They no longer, as a diverse population, become victims of a largely white society. They control the narrative. They can rewrite it. And this project, in the way it’s been received, really shows them that when they speak up, the world is ready to hear them.”

Potts says that the very last lines of her students’ book have already come true, thanks to their hard work and creativity. “Today, Florence’s music can be heard all around the world just like she dreamed of when she was young,” Potts reads. “If someone asks, ‘Who is Florence Price?’, you can tell them.”

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit npr.org.9(MDAyOTk4OTc0MDEyNzcxNDIzMTZjM2E3Zg004))