Reeder’s Movie Reviews: West Side Story

Steven Spielberg’s latest picture arrives in theatres with not only the weight of history and expectation, but also the bittersweet memories of his father and the work’s lyricist. Arnold Spielberg, the film’s dedicatee, died in August, 2020, and Stephen Sondheim passed away last month.

By his own admission, Spielberg the son has wanted to make a movie musical ever since the start of his illustrious career. Now that he has, it invites the inevitable comparison to the first big-screen version of this story, released sixty years ago this fall. That West Side Story, with direction by Robert Wise and choreography by Jerome Robbins, claimed ten Academy Awards, including Best Picture. A tough act to follow.

Spielberg and his collaborators, including the Pulitzer- and Tony Award-winning playwright and screenwriter Tony Kushner, hew more closely to the original 1957 Broadway stage production. In doing so, they’ve put the songs and dance numbers into a more consistently relevant sequence. (An exception: “Cool” has been moved.) They now make even more musical and emotional sense, and they advance the narrative more forcefully, with more motivation associated with the principal characters.

The movie immediately establishes the “slum clearance” project leading to the creation of Lincoln Center, home to multiple arts venues, as its historical and cultural backdrop. Indeed, Kushner’s approach to rewriting the book of West Side Story focuses on an updated, more thoughtful engagement with issues such as racism, assimilation, gender identity, poverty and gentrification. In his screenplay, characters sometimes speak Spanish, proudly and without subtitles.

Importantly, this cast includes far more Latinx performers than the 1961 film. Rachel Ziegler (María) is of Colombian ancestry on her mother’s side. Ariana DeBose’s (Anita) father is Afro-Puerto Rican. David Alvarez’ (Bernardo) parents are Cuban. Josh Andrés Rivera (Chino) is Puertorriqueño. Like all of the other principals, they do their own singing and dancing, another notable departure from the earlier production.

In watching this West Side Story, you’re always aware that it takes place on sets–elaborate, realistic sets constructed in New Jersey. Yet that never diminishes the impact of this tragic story of young love and ethnic gangs in New York City. Spielberg and his regular cinematographer Janusz Kaminski (Schindler’s List, Saving Private Ryan) keep the film visually imaginative and engaging from start to finish, making particularly effective use of drone, panning and tracking shots. The wide-angle overhead views of the gang members arriving for their warehouse rumble, with their shadows advancing across the salt-strewn flooring, register like an homage to the world of film noir.

Then there’s the music. Leonard Bernstein’s brilliant score and Sondheim’s memorable lyrics are iconic for a reason. For this project, Gustavo Dudamel conducted both the New York and Los Angeles Philharmonics, and the cast recorded most of their numbers in the studio for playback on set. However, Ansel Elgort, who plays Tony, insisted that he perform the beginning of “María” on site. When you see Spielberg’s staging of that scene, you’ll understand why.

Elgort (Baby Driver) can often come across as inexpressive on screen, but at least his training and experience as a singer and dancer serve him well here. Ziegler, who prevailed over 30,000 other young women in an open audition for the coveted role of María, had previously sung the role in a local stage production in New Jersey. Her performance is fresh and unaffected, and her singing is technically sound and suitably expressive. DeBose, who has ensemble credits in both the stage and film versions of Hamilton, excels as Anita (arguably a more interesting character than María, as written). “A Boy Like That/I Have a Love,” the duet sung by Anita and María in the aftermath of Bernardo’s death, is wrenchingly beautiful. As the latter, David Alvarez (one of the youngest performers ever to win a Tony for Best Actor in a Leading Role, for Billy Elliot) gets to showcase both his singing skills and his classical dance training.

Aside from Mike Faist as Riff, the Sharks seem more vividly portrayed than the Jets, but that never undermines this production. What does work exceedingly well is Spielberg’s approach to the dance numbers, which have new choreography by Justin Peck. They have style, contrast (no more so than in “Mambo”) and fullness, framed and edited such that viewers can appreciate both the talent and the physical spaces.

One of the picture’s executive producers deserves special credit. Rita Moreno, now 89, earned an Oscar for Best Supporting Actress for her portrayal of Anita in the 1961 film adaptation of West Side Story. She returns here in a gender-altered role. The character of Doc, the drugstore owner who gives shelter to Tony after his time in prison, has become Valentina, his tough-minded widow. A native of Puerto Rico, Moreno brings welcome continuity and authenticity to this version. And, in an inspired choice by Spielberg and Kushner, she sings “Somewhere.”

Steven Spielberg loves to recall how he listened intently to his parents’ original cast recording of West Side Story while growing up in Phoenix in the late 1950s. Reimagining the story on film has required many decades of patience on his part. Now, with this fusion of casting, writing, directing, singing, dancing and acting, Spielberg and his team have created a new classic of its kind, true to the source material but cognizant of our own time. To quote Tony: “Something’s coming, something good…it is gonna be great.” Yes, it is.

More Movie Reviews:

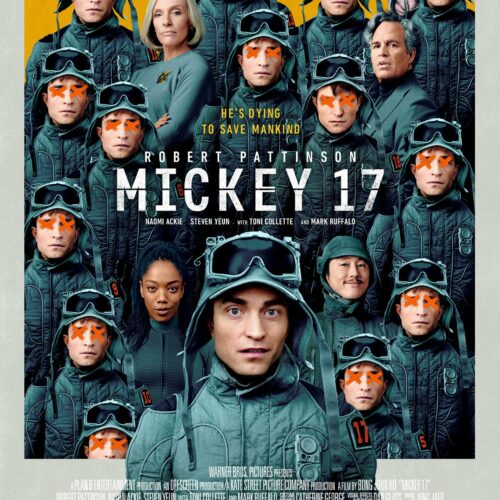

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: Mickey 17

Movie poster of Mickey 17 courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures. Read “You don’t look like you’re printed out. You’re just a person.” In writer-director Bong Joon Ho’s new science fiction

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: A Complete Unknown

In director James Mangold’s new film, Timothée Chalamet portrays the young Bob Dylan (the professional name he adopted at age 21) from 1961-1965. He gives a remarkably nuanced, accomplished performance in a movie that occasionally gets bogged down in truncated or unnecessary scenes, but not too often. The supporting cast shines as well.

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: Nosferatu

A classic tale laced with horrific, religious, folkloric and erotic themes. Robert Eggers seemed destined to make a movie about it. Finally, after a decade of preparation, he has.