Reeder’s Movie Reviews: C’mon C’mon

The writer, director and graphic artist Mike Mills loves to explore family. His own family, to be precise. In Beginners (2010), for which the late Christopher Plummer won an Academy Award, Mills dramatizes his elderly father’s gay relationship with a much younger man. In 20th Century Women (2016), for which Mills himself earned an Oscar nomination for Original Screenplay, he focuses on his mother, portrayed by Annette Bening, and her unconventional lifestyle as a single mom in late 1970s California. Of course, the characters of Oliver and Jamie in those films serve as Mills’ alter egos. His latest project, C’mon C’mon, is the most existential and least coherent in his trilogy (to date), despite its many strengths.

Joaquin Phoenix portrays Johnny, a single and childless public radio journalist who travels around the country with his producing partner interviewing children (not child actors) about their outlook on life. Meanwhile, he volunteers to look after Jesse, a hyperactive nine-year-old whose mother, Johnny’s sister Viv, finds herself trying to cope with her husband’s latest mental health crisis. As further background, their mother suffered from dementia before her passing.

Johnny, for all of his keen professional interest in the lives of kids in Los Angeles, Detroit, New York and New Orleans, clearly has trouble expressing his own emotions and frustrations. Spending so much time with his nephew begins to transform him, if only in fits and starts. The willful Jesse demands attention. He loudly repeats Johnny’s words, and he questions the latest news about his father, whom he fears losing. He challenges his uncle to demonstrate affection, if not love. He provokes him by wandering away on busy streets while Johnny talks on the phone. No wonder Johnny tells the boy, “Maybe we can just take this process slowly and see how it feels.”

Mills interposes the children’s interviews and the uncle-nephew scenes with the brother-sister conversations. Gaby Hoffmann, whose career began in childhood with Field of Dreams and Sleepless in Seattle, gives an impressive performance as Viv, a woman passionately–even desperately–trying to stitch together her relationships with her husband, brother and son. Her scenes with the shaggy, laconic Phoenix, in which they sort out their emotional baggage, quicken the pulse of a movie that generally moves at a measured pace.

Phoenix, in his first feature since his flamboyant, Oscar-winning turn in Joker, registers well here as a soft-spoken and sympathetic, if emotionally stunted, character. As Jesse, the English actor Woody Norman, who just turned twelve years old, developed such strong rapport with Phoenix that Mills allowed them a significant amount of latitude for improvising. And, yes, Norman manages a very plausible American accent.

C’mon C’mon is the latest entry in a bumper crop of crisp, black-and-white films this year (The French Dispatch, Belfast, Passing and the forthcoming The Tragedy of Macbeth). For various reasons, all of their directors have made an aesthetic choice to use a “retro” look to tell historical, nostalgic or deeply personal stories. Then again, the South Korean director Bong Joon-Ho made a black-and-white cut of his Best Picture winner Parasite, coyly suggesting that perhaps that version would become a “classic” like so many pictures of Hollywood’s Golden Age.

Cinematography aside, Mills has created a sensitive story with multiple elements which, unfortunately, never quite cohere. As Johnny the journalist/documentarian conducts his at-home and other on-site interviews with a variety of children, whose concerns range from school to jobs to climate change, his evolving relationship with Jesse seems like a parallel, rather than integrated, part of the narrative. They’re interesting enough, but not connected. Johnny’s transformation, on the other hand, seems believable, and his hand-holding with Jesse and soul-searching with Viv are truly poignant.

Mills populates the soundtrack with a rich array of urban sounds. In fact, Jesse really begins to bond with his uncle when Johnny gives him the shotgun mic and headphones. The movie also features several atmospheric pieces of classical music, including pages from Mozart’s Requiem and Debussy’s Clair de lune.

In making C’mon C’mon, Mike Mills wanted to reflect on his own experience as a father to his son Hopper. As he puts it, “a human being is huge…a film about human beings, if you’re lucky, you’re going to get, like, a sliver.” In this case, the movie is not huge, but it certainly addresses the hugely important aspects of family relationships.

More Movie Reviews:

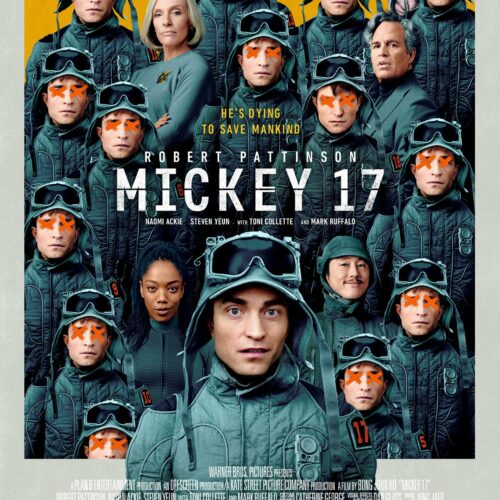

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: Mickey 17

Movie poster of Mickey 17 courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures. Read “You don’t look like you’re printed out. You’re just a person.” In writer-director Bong Joon Ho’s new science fiction

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: A Complete Unknown

In director James Mangold’s new film, Timothée Chalamet portrays the young Bob Dylan (the professional name he adopted at age 21) from 1961-1965. He gives a remarkably nuanced, accomplished performance in a movie that occasionally gets bogged down in truncated or unnecessary scenes, but not too often. The supporting cast shines as well.

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: Nosferatu

A classic tale laced with horrific, religious, folkloric and erotic themes. Robert Eggers seemed destined to make a movie about it. Finally, after a decade of preparation, he has.