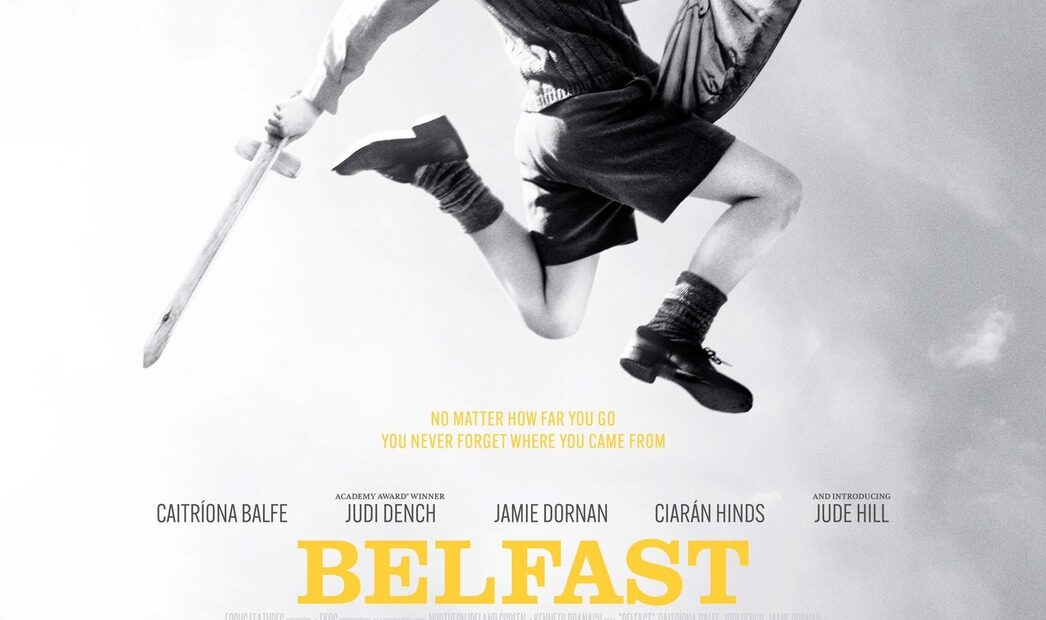

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: Belfast

“The Irish are built to leave,” as one character ruefully observes in Sir Kenneth Branagh’s new film, his twenty-second behind the camera. Indeed, many have departed the home soil, but their abiding attachment to it has prompted a wealth of insight and inspiration. You can add Belfast to the mix.

Branagh, adding to a highly varied résumé as writer and director, has crafted a strikingly beautiful and utterly humane period piece, with his nine-year-old self (played by Jude Hill) at the center of an autobiographical story. Buddy lives with his parents (Jamie Dornan and Caitriona Balfe), older brother (Lewis McAskie) and paternal grandparents (Ciarán Hinds and Judi Dench) in a close-knit, working class neighborhood in the title city in Northern Ireland. Their street is populated by Protestants and Catholics alike, and the year is 1969. The violent “Troubles” are just beginning, and the clouds have gathered over this erstwhile peaceful community. The first approaching mob sounds like a swarm of bees, one of many highlights in the sound design. This terrifies Buddy, of course, but he does his best to remember his devoted Pa’s oft-stated instruction, “If you can’t be good, be careful.” Meanwhile, his father keeps leaving for work in England, as a means of dodging the tax collector and lifting his family into the middle class.

Belfast unfolds as a series of memorable set pieces, with wide overhead shots–the sky almost becomes a personality here–as brief interludes. Branagh and cinematographer Haris Zambarloukos (who previously worked with the director on Sleuth, Thor, Cinderella and Murder on the Orient Express) bring a clear, precise vision to the narrative with the mostly black-and-white visuals and the physical intimacy with the characters. Van Morrison’s songs add the perfect accent on the soundtrack, whether it be a nostalgic or ironic note. In fact, many of his lyrics linger through the scene transitions, making them resonate all the more.

The sound–the musicality–of the language itself also plays an important part in the storytelling. Dornan and Hinds, like Branagh, are Belfast natives. They authentically inhabit this place and time, along with the rest of the superb cast, who function really well together as an ensemble. Caitriona Balfe shines as Ma, a woman compassionate enough to keep a firm grip on her family and brave enough to confront the partisan gangs threatening to tear their beloved city apart in the name of religion. (Branagh has cited his immediate family’s “nominal allegiance” to their Protestant faith.) Ciarán Hinds contributes sage advice, wit and warmth as Pop, a “deep thinker” who appreciates personal integrity, his own mortality and the value of outdoor plumbing. Jude Hill, Branagh’s alter ego as the wide-eyed Buddy, gives a revelatory performance, one of the best recently by a child actor.

If you’ve seen Alfonso Cuarón’s brilliant, Academy Award-winning Roma (2018), then you can readily appreciate the look and sensibility of Belfast. Both employ black-and-white cinematography to help express the dramatized recollections of directors about their childhoods and early artistic influences in Mexico City and Northern Ireland, respectively. You can expect Belfast to bask in Oscar’s glow, too, in the near future.

Kenneth Branagh recently turned 60. Perhaps the time had arrived for serious reflection on his part. Not only do we witness the conflicts of his childhood, with Buddy trying to master his math lessons, pursue a crush on the smartest girl in his class–a Catholic–and make sense of the bombing and looting, we also get to appreciate his youthful fascination with television and film. Look for snippets of Star Trek, High Noon, Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, Lost Horizon, One Million Years B.C. and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, all in their colorful hues. An uneven mix of cinema, but the kinds of stories which would have mesmerized a boy in Ulster in 1969. The family marvels at the moon landing on the small screen at home, as well as the seemingly realistic special effects on the big screen at a local theatre. If you pay close attention, you’ll get a glimpse of the director in an Alfred Hitchcock-like cameo.

Branagh frames his movie with expansive, drone-captured shots of contemporary Belfast, shot in color. The ending features several captions, by way of dedication: “For the ones who stayed. For the ones who left. And for all the ones who were lost.” Belfast is an artfully made, deeply personal film, rich with period detail, common wisdom, music, pathos and humor. (A box of “biological” detergent easily qualifies as an absurd, laugh-out-loud moment.) It evokes genuine emotions from its audience, without pandering to it. And it fully justifies Granny’s observation that “We all have a story to tell…what makes each one different is not how this story ends, but rather the place where it begins.” Amen.

Related Stories:

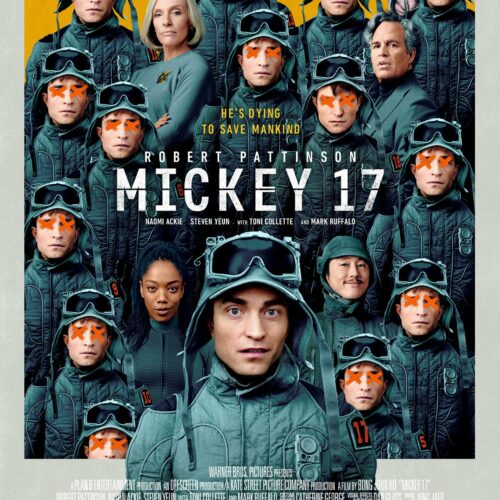

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: Mickey 17

Movie poster of Mickey 17 courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures. Read “You don’t look like you’re printed out. You’re just a person.” In writer-director Bong Joon Ho’s new science fiction

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: A Complete Unknown

In director James Mangold’s new film, Timothée Chalamet portrays the young Bob Dylan (the professional name he adopted at age 21) from 1961-1965. He gives a remarkably nuanced, accomplished performance in a movie that occasionally gets bogged down in truncated or unnecessary scenes, but not too often. The supporting cast shines as well.

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: Nosferatu

A classic tale laced with horrific, religious, folkloric and erotic themes. Robert Eggers seemed destined to make a movie about it. Finally, after a decade of preparation, he has.