Reeder’ Movie Reviews: Dune: Part One

The risk of the project was destined to match the scale of journalist-turned-author Frank Herbert’s Dune. Denis Villeneuve’s conception has arrived in theatres (and HBO Max), and its sequel has already been greenlighted by Warner Bros. After two viewings, his intentions have become more clear and convincing.

So much distinguishes Herbert’s ambitious, philosophical science fiction novel, written here in the Northwest. Its 1965 publication captivated readers and challenged other writers. Not surprisingly, filmmakers found it irresistible, but the material defied the contrasting approaches of Alejandro Jodorowsky and David Lynch on the big screen and John Harrison (if only because of financial and technical limitations) on the small one.

Villeneuve, the Canadian writer-director, has built a substantial reputation in the past dozen years for a series of imaginative, compelling dramas: Incendies, Prisoners, Sicario, Arrival and Blade Runner 2049. With Dune, a book he discovered in his early teens in Québec, he wanted to more fully respect Herbert’s subject matter than his predecessors. He succeeds, almost to a fault.

To his credit, he captures the immense, unforgiving landscapes of the planet Arrakis with his wide angles and experimental exposures. Wisely forgoing the use of green screen, he shot on location in Jordan and the United Arab Emirates. (The Oregon Dunes had inspired Herbert, a native of Tacoma.) To see the human characters in Dune against this backdrop is to appreciate the grandeur of the natural world, however stark, while putting all of their machinations in their proper perspective. At the same time, he largely dispenses with the novel’s wealth of inner monologues and family/palace intrigues in order to focus more closely on the emotional content of the source material.

Interestingly, his overall approach to the storytelling here almost defies style. He maintains such rigor and discipline in the way he frames the physical world of Dune, with its basically monochromic color palette, that the human part almost seems “objective” and insufficiently vivid, despite the quality of the acting.

For all of his admirable diligence, Villeneuve and his co-screenwriters have also substantially muted the overtly Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) themes and language in Herbert’s meticulously-crafted tale. The concepts of “messiah” and “holy war” persist. So does the presence of “indigenous people,” but “jihad” and “Zensunni” have disappeared. Of course, the spice, the most precious resource in the galaxy, remains. As if to emphasize the earthly and contemporary resonance of this futuristic, otherworldly tale, a wounded Baron Vladimir Harkonnen (Stellan Skarsgård, memorably depicted both visually and vocally) luxuriates in a pool of bubbling petroleum.

Academy Award-winner Hans Zimmer’s music strikes an insistent note. However, its Middle Eastern undertones bring it (and the movie) awkwardly close to Lawrence of Arabia at times. It just becomes too literal, especially with its female voices chanting a “made-up language,” to quote the composer. Ironically, Zimmer passed on scoring Tenet, the most recent film made by his frequent collaborator Christopher Nolan, because of his keen interest in Dune the book.

Villeneuve elicits solid performances here. Timothée Chalamet captures all of the defining qualities of Paul Atreides, the physically unimposing young man destined to inherit the responsibility of governing Arrakis (the Dune of the title). He exhibits stubbornness, naïvete, courage (if inexperience), loyalty and sensitivity. The melancholy, too, with which the teenaged Villeneuve identified. His facial expressions during the trial of pain administered by the Reverend Mother Mohiam (an austere Charlotte Rampling) offer one of the movie’s standout moments. He has several more in the scenes with his mother, Lady Jessica (Rebecca Ferguson, as expressive as ever). Indeed, they share the iconic litany, “I must not fear. Fear is the mind-killer…the little death that brings total obliteration.” Their private signals highlight a recurring visual theme in the film, as the camera frequently calls our attention to hands.

Kudos to Jason Momoa as well. His portrayal of the brash, devoted Duncan Idaho lends energy to the picture. Along with Josh Brolin as Gurney Halleck, the non-singing troubadour-fighter, he provides the occasional dash of sly humor absent from Villeneuve’s other sci-fi spectacles. Oscar Isaac lends a noble presence as Duke Leto, Paul’s father and the head of the House of Atreides, who understands “desert power.”

Despite all of the Middle Eastern/North African elements in Herbert’s writing, the cast lacks any MENA actors. (Blade Runner 2049, on the other hand, features the renowned Palestinian actress Hiam Abbass as a replicant resistance leader.) We do begin meeting the Fremen, the resident people of Arrakis, including Javier Bardem as the leader Stilgar, Sharon Duncan-Brewster as the (now female) planetologist Doctor Liet Kynes, and Zendaya as the resourceful warrior Chani, the subject of Paul’s visions of the future. She has only seven minutes of screen time in this movie, but you can expect her to assume a leading role in the next installment, especially given Villeneuve’s stated desire to bring forward the female characters in this sprawling saga.

With Part Two now in the works, you can likewise anticipate much more attention to be lavished on the prominent ecological and evolutionary themes in Herbert’s novel. As for the customs, language (largely derived from Arabic), special skills and civilization of the Fremen, the voiceover at the very beginning of Part One establishes that intention, but its fulfillment awaits as well.

Now, if your idea of wish fulfillment involves gigantic sandworms, you will not be disappointed. They are spectacular here, and their first appearance (combined with a daring rescue mission) is nothing short of brilliant. Even the formidable Christopher Nolan has congratulated his fellow director for raising the CGI bar with this picture.

Taken as a whole, Dune: Part One deserves high marks for its respectful vision, impressive production design and attention to detail. It thoroughly parts ways with David Lynch’s substantially condensed, stylistically eccentric and roundly (though excessively) criticized 1984 adaptation. Granted, with Denis Villeneuve and his team, you have to wait two more years for another two hours-plus of storytelling. Dune, like the mystery of life itself, is “a reality to experience.” If you have a choice, see it on the biggest screen possible.

More Movie Reviews:

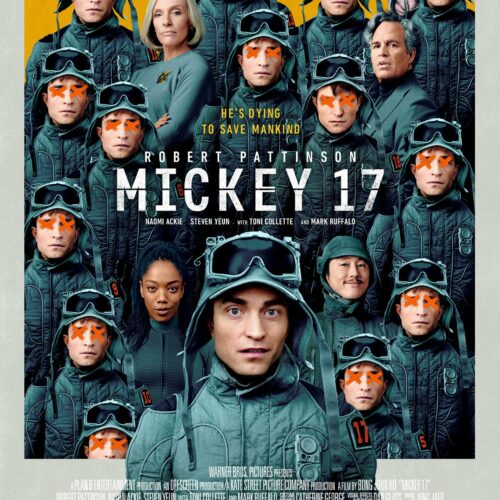

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: Mickey 17

Movie poster of Mickey 17 courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures. Read “You don’t look like you’re printed out. You’re just a person.” In writer-director Bong Joon Ho’s new science fiction

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: A Complete Unknown

In director James Mangold’s new film, Timothée Chalamet portrays the young Bob Dylan (the professional name he adopted at age 21) from 1961-1965. He gives a remarkably nuanced, accomplished performance in a movie that occasionally gets bogged down in truncated or unnecessary scenes, but not too often. The supporting cast shines as well.

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: Nosferatu

A classic tale laced with horrific, religious, folkloric and erotic themes. Robert Eggers seemed destined to make a movie about it. Finally, after a decade of preparation, he has.