Geological Survey Explores Idaho’s Salmon Region For Cobalt

BY RACHEL SUN

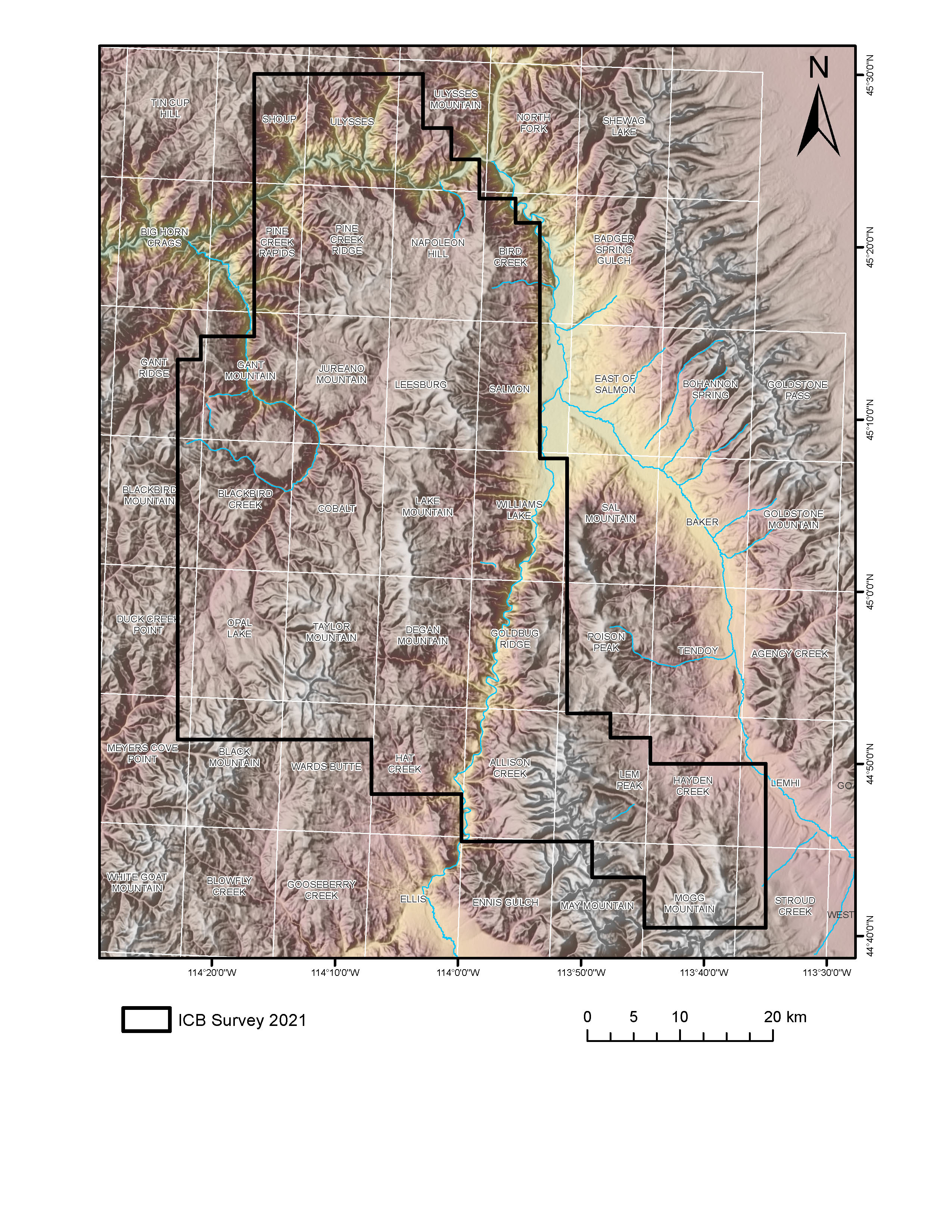

Work to provide information on cobalt deposits in Idaho’s Salmon region is set to be completed this month as part of a public-private partnership. But there are environmental and tribal concerns about mining near the Salmon river.

The roughly $600,000 project is being paid for by a combination of federal funds and monies from the Idaho Cobalt Company, New Jersey Mining Company and Idaho’s Revival Gold Incorporated, said Claudio Berti, director of the Idaho Geological Survey.

Cobalt is considered a critical mineral for national security, and has numerous applications in electronics and clean energy, he said, including batteries used to power electric vehicles and store solar energy.

Though no mining has begun, the information gleaned from the survey could pave the way for future operations.

To conduct the survey in the rugged terrain of Idaho’s cobalt belt, IGS is using helicopters with attached devices that measure the magnetic and radiometric signature of the region.

The helicopters fly roughly 100 meters above the surface, and will eventually allow geologists to produce maps and understand what minerals are at the surface and subsurface. That work is preceded by several years of field mapping in the region by IGS.

Helicopter with installed instrument to collect magnetic and radiometric data in the search of cobalt near the Salmon River. Courtesty: USGS

The goal for the study is to ultimately move the U.S. toward independence from foreign sources of cobalt according to Berti. “There are minerals and elements that the U.S. uses, and any modern economy really, uses. And there [are] short supplies, and the supplies are mostly under a specific monopoly — almost a monopoly — and so, the idea is starting to lose dependence from other nations and from external sources in gathering those. Cobalt is one of them.”

Bonnie Gestring, a northwest representative with the nonprofit conservation group Earthworks, said it’s important for the public to understand the ecological and public health impacts of mining. “Mining is the leading source of toxic releases in the United States. So, it releases more hazardous materials to the air, water and land than any other industry by far. So hardrock mines often result in long term water pollution and other types of environmental impacts, and cobalt mining is really no exception to that.”

Gestring pointed to the Blackbird Mine, a now-inactive cobalt mine 25 miles west of Salmon and current superfund site — that is, a highly polluted area that requires a continuous response to clean up hazardous material.

One concern for cobalt mines, in particular, is what’s called acid mine drainage which has negative implications for aquatic life and public health. Acid mine drainage occurs when sulphide minerals are exposed to air and water during the mining process. Sulphides are also commonly found in association with cobalt.

Gestring recognizes the need for renewable energy resources, but believes more can be done to reduce the demand for new cobalt, such as recycling batteries. Current mining laws in the U.S. have remained largely unchanged since the inception of the General Mining Law in 1872.

One of the updates Gestring wants is to increase the fees hardrock mines pay to the public for the minerals. She would like those fees to be more comparable to oil, gas and coal. As it stands, mining is prioritized over all other land use, and fees are generally minimal.

According to the U.S. Government Accountability Office, as of 2018 there were 748 hardrock mining operations on federal land, most of which did not pay royalties — though it’s not clear how productive those mines are, as agencies don’t usually collect data on mines if they’re not required to pay royalties.

Although mining companies are fined if they violate the Clean Water Act, it’s not always a big enough incentive for a company to change its practices according to Gestring. “What we often see are violations that continue for, really, for years, because the penalties aren’t high enough to really force the company to address the problem.”

Hardrock mining has historically faced pushback from Native American tribes – who are often disproportionately affected by their environmental impacts. Though the federal government is required to consult tribes that could be affected by mining operations, the quality and depth of those consultations vary.

In a 2021 testimony, Samuel Penney, Chairman of the Nez Perce Tribal Executive Committee to the House Natural Resources Subcommittee on Energy and Mineral Resources, said the 1872 General Mining Act needs reforming. “Mining exploration and mines should not be allowed to displace other recreation, resource, and spiritual values and legal rights on federal public land,” he said. “The urgent need for both statutory and regulatory form on this issue is exemplified through current and historical mining activities on the ceded and reservation lands of the Nez Perce people, or in our language the Nimiipuu.”

Despite those ongoing calls for reform of current mining laws, much of the cobalt used is mined in other countries with even looser regulations. Decreasing dependence on international sources for the mineral could theoretically lead to more oversight of the mining operations for the cobalt Americans use according to Claudio Bert. Berti: “The reason why it’s easier and cheaper [in other countries] is because the regulations are much less [strict]. My theory is it is the responsibility of a civilized nation to make sure that you don’t just forget the downstream part of what you’re using. And so we definitely have the capacity and the legislation and the technical skills to do mining in a responsible way. That doesn’t mean that it is accident-free, or problem-free. But we definitely have the ability to do it in the most responsible way.”

Related Stories:

New mural in children’s section of Lewiston City Library tells Nez Perce creation story

Nez Perce tribal members Renee Holt and Crescentia Hills see the mural of the Nez Perce creation story for the first time at a library event on Feb. 6, 2025.

More than $30 million in restoration projects taking place in North-Central Idaho

This photo from August 2020 features Rocky Ridge Lake, a popular hiking and camping site in the Nez Perce-Clearwater National Forests. (Credit: Lauren Paterson / NWPB) Watch Listen (Runtime 1:03)

Centralia, Wash.’s coal plant has to close next year. Can Pa. communities learn from Centralia’s transition?

By: Rachel McDevitt, StateImpact Pennsylvania at WITF This story was produced as part of Climate Solutions, a collaboration focused on community engagement and solutions-based reporting to help Central Pennsylvania move toward