Reeder’s Movie Reviews: The Many Saints of Newark

When Richard (“Dickie”) Moltisanti suggests that “pain comes from wanting things,” you can rest assured that others will share his pain, and that of his extended family. Welcome back to the mean streets and moral ambiguity of Newark.

Creator, co-producer and co-writer David Chase revisits familiar territory with this operatic prequel to The Sopranos (1999-2007). If you’re familiar with that legendary television series, you’ll readily identify the basic elements on the big screen. The location sets. The dark humor, often laced with profanity. The pangs of conscience. The family loyalty and betrayal. The swift, brutal violence. The film doesn’t really elevate the original material, but it successfully recreates it.

The story begins in 1967, during a summer of organized crime rivalries and racial disturbances. The Moltisantis and the Sopranos have associates in the black community, most notably the ambitious Harold McBrayer, played by Leslie Odom, Jr. However, while the city’s African-American population experiences the worst kind of police brutality in the Central Ward, the Italian-American families only see a threat to their illicit empire.

This is the formative period for the young Tony Soprano, played as an adolescent by William Ludwig. With his father serving a decade-long prison sentence, he’s already begun pursuing the family business, running a betting operation on the grounds of his middle school. Its guidance counselor identifies him as a “leader,” but an underachieving student. Uncle Dickie becomes his mentor, as well as the facilitator for his love of music. (A veritable Who’s Who of talent from the time appears on the soundtrack.) Tony’s loving but exasperated mom, Livia (Vera Farmiga), has her hands full.

If Chase and his collaborators have prominently integrated themes of racism and police brutality into their narrative, almost as if to provide historical context to today’s Black Lives Matter movement, they have pointedly overlooked the #MeToo era. The casual misogyny remains intact. The women may voice their opinions–and they pointedly do–but they have clearly defined roles to play (wife, mother, mistress). Chase has defended this aspect of the script, saying it rings true to the period and the source material. You’ll find no analyst here. Lorraine Bracco need not apply.

As Dickie, Alessandro Nivola gives a charismatic, commanding performance. He looks and acts like a movie star. He values family and loyalty, but you don’t want to cross him. No one escapes his wrath, if they violate his shifting moral code. No surprise where the young Tony ultimately looks for guidance.

Michael Gandolfini, the son of the late James Gandolfini, plays Tony Soprano as a young adult. He watched the TV show to acquaint himself with the character, and it shows. He perfectly replicates his famous, award-winning dad’s shifty eyes and shambling walk. Admittedly, he lacks the acting chops at this point in his career to fully capture the shyness and sensitivity in the character, but his physical presence suffices here. After all, this is ultimately Dickie’s film. Tony is a witness to his own transformation.

Most of the rest of the supporting cast performs admirably. In addition to Farmiga and Odom, special credit to Corey Stoll as “Junior,” Jon Bernthal as “Johnny Boy” (Tony’s father), Ray Liotta as a deadpan “Hollywood Dick,” Billy Magnussen as “Paulie,” Joey Diaz as “Buddha,” and Michela De Rossi (in her English-language debut) as Giuseppina, Dickie’s “goomah.”

Oscar-nominated Production Designer Bob Shaw (The Irishman) captures the everyday, mundane locales, with a wealth of period detail. Cinematographer Kramer Morgenthau (Boardwalk Empire, Game of Thrones) contributes moments of real poetry, including the billowing red smoke arising from a downtown Newark convulsed in fire and street violence. Alan Taylor, a veteran of the original TV show, contributes crisp, effective direction.

If you’re wondering about that future mentor-protégé relationship, Tony Soprano only meets his cousin Christopher Moltisanti as an infant in this story. However, Michael Imperioli, who played the adult Christopher so brilliantly on the small screen, provides sly, voiceover narration. In the end, The Many Saints of Newark paints a vivid portrait of a specific time, place and extended family. It will leave you wanting more, but it will not be painful. Honest.

Related Stories:

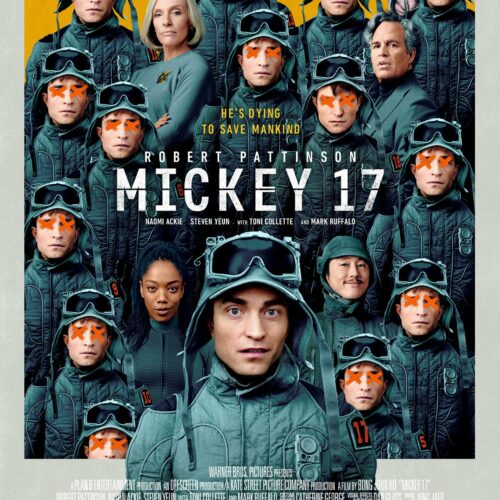

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: Mickey 17

Movie poster of Mickey 17 courtesy of Warner Bros. Pictures. Read “You don’t look like you’re printed out. You’re just a person.” In writer-director Bong Joon Ho’s new science fiction

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: A Complete Unknown

In director James Mangold’s new film, Timothée Chalamet portrays the young Bob Dylan (the professional name he adopted at age 21) from 1961-1965. He gives a remarkably nuanced, accomplished performance in a movie that occasionally gets bogged down in truncated or unnecessary scenes, but not too often. The supporting cast shines as well.

Reeder’s Movie Reviews: Nosferatu

A classic tale laced with horrific, religious, folkloric and erotic themes. Robert Eggers seemed destined to make a movie about it. Finally, after a decade of preparation, he has.