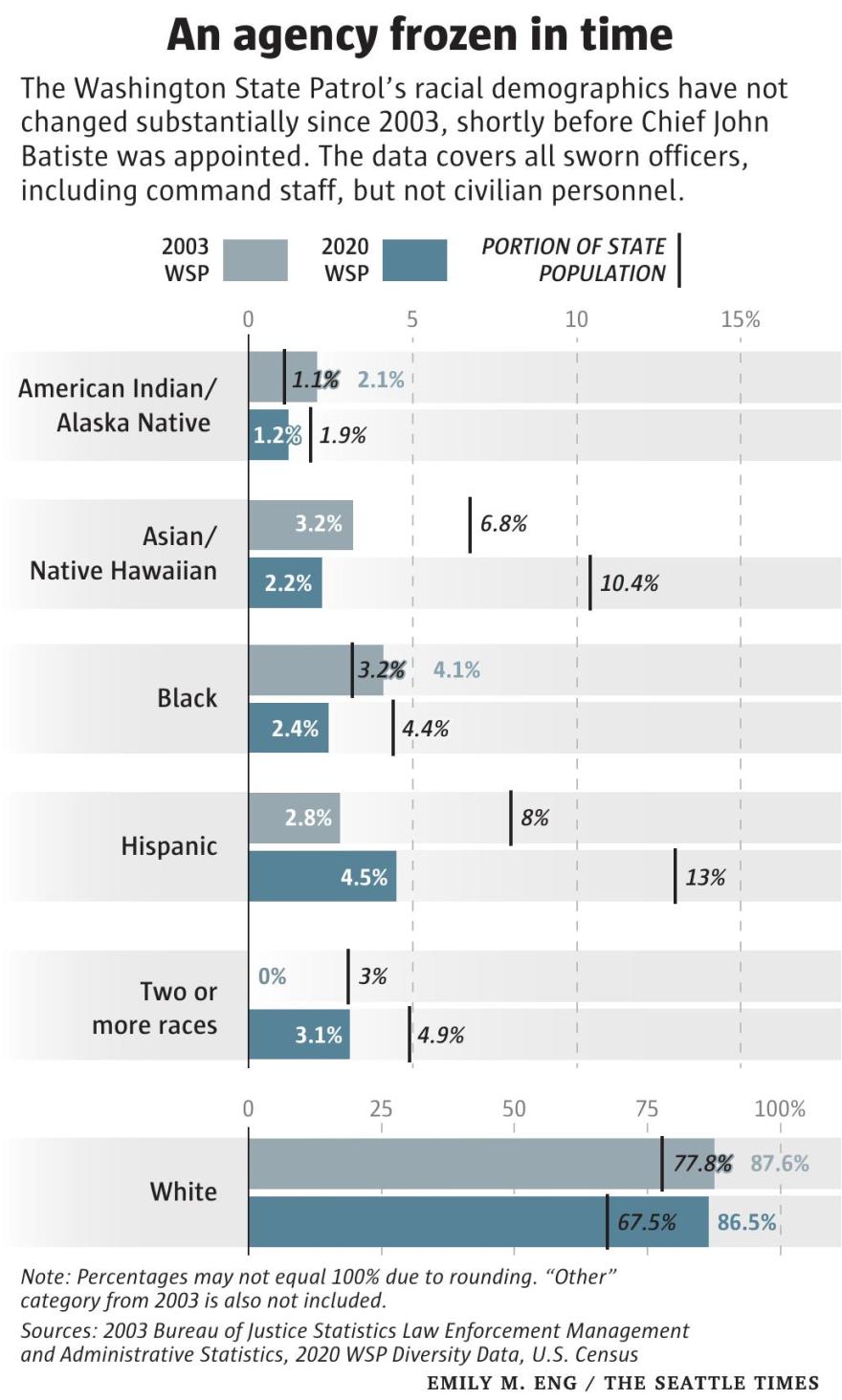

The Washington State Patrol is as vastly white today as it was nearly 20 years ago, before the agency’s first Black chief took charge.

Throughout that time, the WSP has struggled not just to diversify its ranks, but to recruit and hire enough “warm bodies” — in the words of the chief — to fill its open trooper positions.

A stage late in the hiring process has been repeatedly targeted as a problem: the psychological evaluation. People inside and outside the agency have warned that the department’s longtime psychologist, Daniel Clark, screens out too many candidates. Some are lost to other police departments.

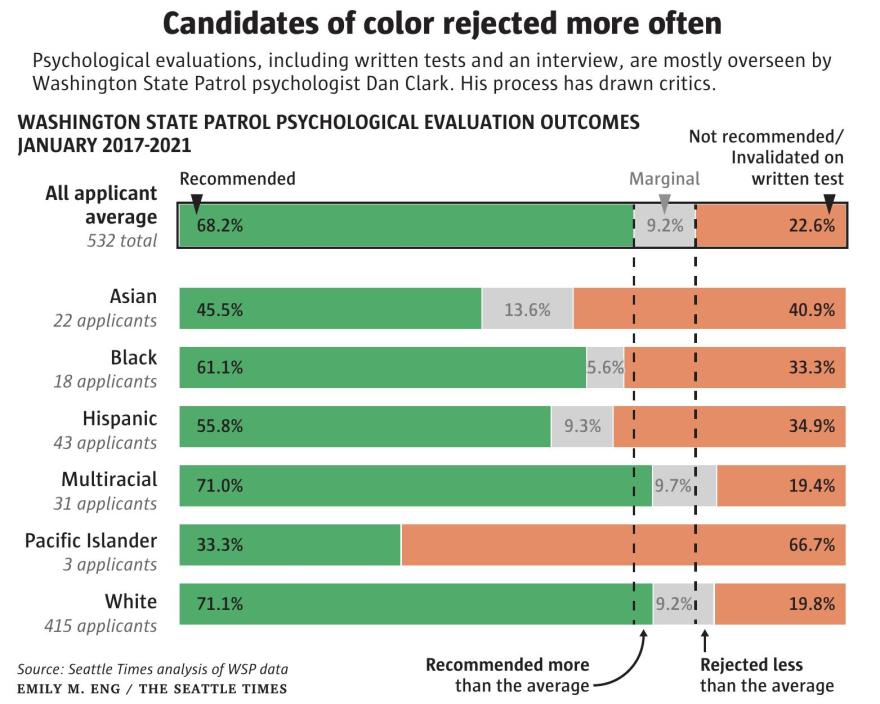

But it wasn’t until earlier this year, when yet another consulting firm weighed in, that the WSP took notice of a concerning side effect: the psychological evaluation appears to disproportionately reject candidates of color.

Consultants from Deloitte, a multinational firm, found that minorities in a recent group of applicants failed at significantly higher rates than their white counterparts.

“With that being brought to our attention, we want to make sure we get to the bottom of that,” Chief John Batiste said in an interview Thursday. “The last thing that I want to have is adverse impacts to any candidates.”

The disparity, in fact, has existed since at least 2017. Internal data reviewed by The Seattle Times and public radio Northwest News Network shows the psychological screening rejected 20% of white candidates over the four years ending in January. In contrast, 33% of Black candidates, 35% of Hispanic candidates and 41% of Asian candidates were not recommended for a job, according to the data.

The WSP, the second-largest force in Washington after the Seattle Police Department, has also faced criticism for disproportionately policing people of color. A new Washington State University study obtained by The Times and Northwest News Network found that between 2015 and 2019, Hispanic, Native American and Black drivers are more likely to be searched than white motorists — for Native Americans, nearly three times as much.

The WSP notes the study didn’t find bias in initial traffic stops, and some racial gaps had narrowed since past studies. The agency has also stepped up recruitment in communities of color — more than 30% of applicants in each of the past three classes were from underrepresented race and ethnic groups, according to Deloitte. Recently, the WSP hired its first diversity, equity and inclusion officer. Batiste said the latest recruit class represented a “record high” in diversity.

But the chief, who identified diversity as a personal priority soon after being appointed, still has a long way to go to win over critics.

Before he took over in 2005, 88% of the troopers were white, according to a U.S. Department of Justice survey. The numbers have barely budged since — as of last year 87% of troopers were white, WSP data shows — while the ranks of women troopers rose slightly, to 10% of the force. The percentage of white Washingtonians over the same period went from 78% to 68%, according to the U.S. census.

“I’m just embarrassed for where the State Patrol is, particularly with a Black chief who’s been there for 17 years now,” said state Rep. John Lovick, who for three decades was one of the few Black WSP troopers, and then was Snohomish County sheriff. “It’s disgraceful.”

Batiste pushes back on this sort of criticism and bluntly asks of his detractors: “What are you doing to help me diversify the agency?”

One thing the Deloitte consultants recommended is to “diversify the perspectives” of evaluators by hiring a new psychologist. But Batiste says he is sticking with Clark, who has conducted more than 3,500 pre-employment psychological exams in 27 years at the agency and others.

“That’s a recommendation, and I reject that recommendation,” Batiste said. “I have a full-time psychologist.”

In an interview, Clark defended his process and blamed any racial imbalance on the national written tests he administers.

“I treat everybody as an individual and make my recommendations based on an individual assessment,” Clark said. “Psychologically, I don’t believe that there is bias.”

He also isn’t the final arbiter, Clark said, noting the WSP’s human resources captain is the official hiring authority, and an assistant chief can mediate disputes between him and the human resources captain.

But in practice, current and former WSP human resource officials said, when Clark rejects a candidate, the chances of hiring them are slim to none.

“Out of place”

Kathleena Ly, a first-generation Cambodian American, wanted to help transform the Washington State Patrol into one that reflected the diversifying state.

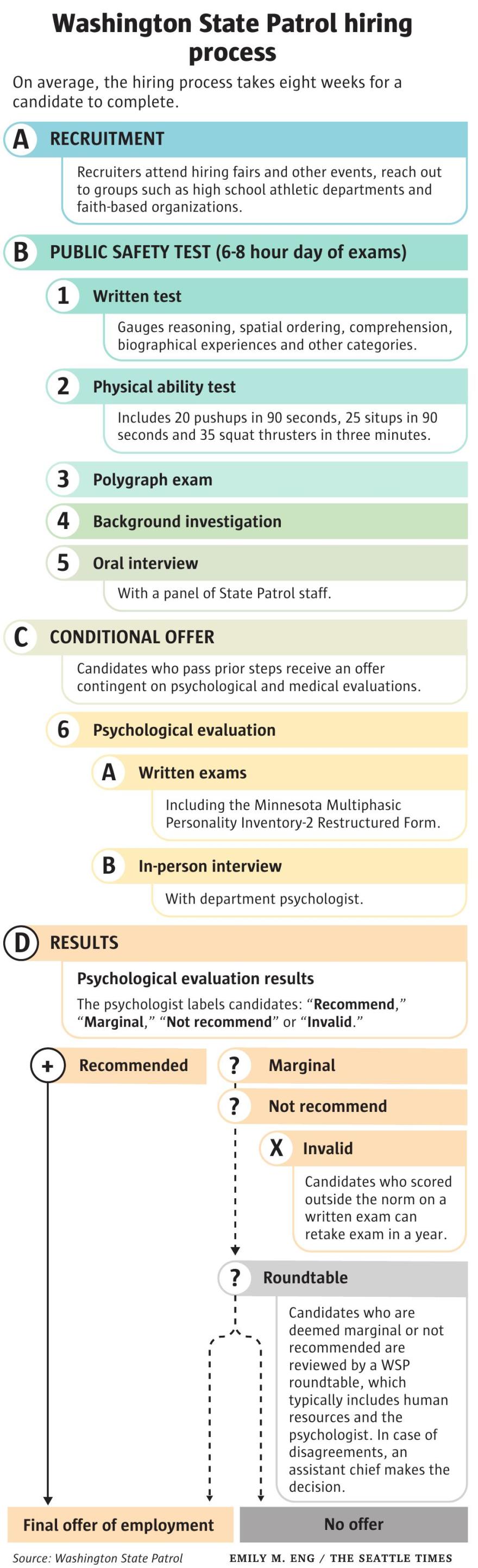

She was encouraged to apply by two high-ranking Black members of the WSP brass in 2019. With a degree in public health, Ly advanced through a rigorous six-step application process, including a background check and polygraph, and received a conditional offer — well on her way to becoming a trooper.

The next step was the psychological evaluation by Clark, who is white. For her, and many other candidates, that was the end of the line. She cried during the interview, recounting a childhood trauma. Ly felt Clark didn’t give her the chance to explain how it did not define her as an adult. (Clark said he couldn’t talk about specific candidates, but emphasized it’s up to an applicant to demonstrate resilience from trauma.)

Ly may never know why Clark rejected her; WSP denied her request to see Clark’s report. But she recalled a cultural disconnect with some phrasing on written tests as she churned through questions.

Kathleena Ly was encouraged to apply for a Washington State Patrol trooper job in 2019, but was denied after the agency’s psychology evaluation. She said the process left her feeling culturally “out of place.” (Bettina Hansen / The Seattle Times)Friday August 27, 2021 in Kent. CREDIT: Bettina Hansen/The Seattle Times

“Especially growing up as an Asian American and hanging around with mostly people of color my whole life, there was just that lack of jargon that I didn’t grow up hearing,” said Ly, who now qualifies people for benefits at another state agency. “I definitely felt out of place.”

When candidates get to the psychological evaluation, Clark administers written assessments meant to gauge personality and detect mental disorders. Candidates can be deemed “invalid” if they skip many questions. Clark also may invalidate candidates if their results show they are portraying themselves in an overly positive light, although other police psychologists say this is a misapplication of the test.

After scoring the tests, Clark sits down with candidates for a 30- to 60-minute interview. He then issues one of three ratings: recommend, marginal or not recommend (which include “invalid” candidates).

Recommended candidates typically get a final job offer (they could later be dropped at the academy and other pre-trooper stages). The rest of the candidates are considered by a roundtable that includes Clark and staff from the Human Resources Division. Marginal candidates sometimes move forward, and those labeled as not recommend “very rarely” advance, said Capt. Jason Ashley, the current head of human resources.

Earlier this year, the WSP received a detailed road map from Deloitte, listing ways to bridge its diversity gaps. Among the report’s findings: Clark’s process is a problem.

“Every focus group and multiple key executives reported concerns of bias in the psychological evaluation process and recommended a review of the process,” the consultants wrote. “Without diversification of evaluators, there is not a system in place for appeals or second opinions. This could be a contributing factor to the high rates of failure for all applicants, and especially applicants of color.”

Clark and Batiste took issue with the Deloitte findings, saying they were overstated or unspecific. Nonetheless, Clark said the assertion of “adverse impact” on minorities struck them as an important critique, “and so I believe that we are taking that seriously. And we’re looking at potential solutions.”

In response to the Deloitte report, WSP said it plans to contract with an outside auditor to review the entire psychological evaluation, including “how to reduce/eliminate all forms of bias, if any, in the process.”

Meanwhile, out on the highways that the WSP polices, troopers ticketed or arrested Hispanic and Asian and Pacific Islander motorists at disproportionate rates, according to the WSU analysis, which controlled for other factors like the seriousness of violations.

Troopers, the report says, found less contraband on Black and Hispanic drivers than on white drivers, “which may indicate that probable cause standards are lower for searches of these groups.”

“The gatekeeper”

The WSP turned 100 this year, but Clark is just its third psychologist.

Clark, 63, received his master’s degree in 1986 and Ph.D. in 1991 from the Rosemead School of Psychology at Biola University, an evangelical Christian college in Southern California. The program blends Christian theology with clinical psychology.

Clark served as an Army psychologist deployed overseas and as a clinical psychologist at Madigan Army Medical Center near Tacoma before joining the WSP in 1994. Clark first worked together closely with Batiste when Batiste was a captain in the Tacoma field office, and Clark helped a trooper who was seriously injured in a collision. Clark made $126,700 in 2020, according to the state’s salary database.

Daniel Clark, psychologist for the Washington State Patrol. CREDIT: Washington State Patrol

He has established himself as an expert on officer suicides and helping agencies recover from traumatic events like natural disasters and terrorist attacks. He served five years on the executive board of the International Association of Police Chiefs’ police psychology section. Unlike many of his peers nationwide, Clark is not board-certified in the specialized field of police psychology.

Rick Ward passed Clark’s screening process when he was hired as a trooper in the 1990s and served 25 years, including as an instructor at the WSP academy. When Ward’s son, who is white, decided he wanted to follow in his father’s footsteps, he — like Ly — made it all the way to the psychological evaluation. But in his case, Clark rejected Ward’s son based on the written tests alone.

The Seattle Times agreed to keep Ward’s son unnamed because he now works as a police officer in another state and doesn’t want his dispute with the WSP to harm his career.

Alleging that Clark’s process was “neither fair nor equitable” because he failed to interview him in person, as a state statute appeared to require, Ward’s son filed a complaint with the state Examining Board of Psychology in 2013.

Chief John Batiste has led the Washington State Patrol since 2005. He joined the agency as a trooper in 1976. CREDIT: Austin Jenkins

The board ultimately didn’t find evidence of unprofessional conduct. But Clark, while the investigation was underway, changed his methods to always interview applicants who take the written tests — even if their scores are deemed “invalid.”

That doesn’t change the fundamental problem, Ward said. “One guy is the gatekeeper, and that is Clark,” he said. Good applicants will come through and “then you have Dr. Clark take a look at them, and it’s a gamble.”

Behind the scenes, Batiste defended Clark to the Department of Health investigator: “I have great respect for Dan,” he wrote, recounting Clark’s work helping two troopers’ families after they were killed.

Years of red flags

But the DOH investigation was just the first in a string of red flags about Clark’s methods.

In 2015, Capt. Travis Matheson saw a stream of “invalidated” results cross his desk in the WSP’s human resources department, which he oversaw at the time. Trying to figure out what was going on, his team spoke with national experts and psychologists across the state who screened candidates at more than 65 police agencies.

Matheson, then a 23-year veteran trooper, began questioning Clark’s approach. He was concerned enough that he drafted a four-page summary of problems, which he provided recently to The Times and Northwest News Network. Matheson says he sent it to his boss, an assistant chief. The WSP says it can find no record of it.

Clark, Matheson wrote, rebuffed a suggestion to compare his psychological reports to candidates’ later job performance — a process industry experts say is best practice.

At the time, Clark was using a version of a written psychological exam that was more than a quarter-century old, and he had not adopted the latest version and its scoring system, which is intended to minimize cultural bias.

Matheson also noted comments Clark made about candidates during roundtable meetings: one identified as white, “but he looked Asian to me.” Another candidate had a “creepy smile.” Clark also said a woman candidate scored too high on the masculine scale, Matheson wrote.

Asked recently about the comments, Clark said he no longer identifies applicants by ethnicity in roundtable discussions. The agency’s current spokeperson said the “alarming statements” in the summary “are not consistent with the caliber or work ethic we have experienced with Dr. Clark over his lengthy tenure.”

Emails show Matheson pressed Clark on his process, and the criticism wasn’t well received. “Please trust me to know how to do my job,” Clark wrote Matheson.

Things got so tense between the men that they ended up in the chief’s office. Instead of discussing Matheson’s concerns, Batiste said the meeting focused on the need for the two to “be professional within the workplace.”

“Batiste told me to stay in my lane,” said Matheson, who has since retired. (Batiste remembers it differently.)

The spotlight on Clark persisted. A 2016 legislative report examined the WSP psychological evaluation, as part of a larger review when resignations and retirements within WSP were climbing. The report determined that the psychological stage was failing WSP candidates at a rate above peer agencies.

“This difference is significant,” the state’s consultants from the PFM Group wrote, “and results in the disqualification of a number of otherwise-qualified candidates.” Some of the rejected recruits were later hired by local police departments or sheriffs, they noted.

The same month the report came out, Clark began using the newer version of the main written psychological exam, as the consultants recommended. The WSP also created an appeals process in response, allowing an assistant chief to overrule those not recommended — a process that has never been used in the five years since.

But one recommendation the agency brass turned down: Outsource some or all of the psychological screenings. Except for emergencies, the evaluations remained in Clark’s hands.

State Sen. Kevin Van De Wege, D-Sequim, asked Batiste at a hearing in 2017 about progress on the psychological evaluation. Batiste said he had sent Clark to training in Chicago, and the department had “greatly reduced the number of folks who were failing.” Van De Wege, who is a firefighter, asked for specifics, and the chief said his staff could send them.

Internal emails obtained by The Times and Northwest News Network show a scramble to answer the lawmaker’s question. Clark’s passage rate, according to his own data, had actually dropped since the PFM Group report recommended changes, although it had been on an overall upward trajectory since 2012.

Van De Wege said recently he has no record of the WSP sending him the data he sought, and remains concerned about Clark’s role.

“I think it should be the goal of the State Patrol to have a force that looks very much like the people they serve,” said Van De Wege. “And I think in that regard, the State Patrol is currently failing, mainly because of the subjective hiring process.”

Outside the norm

When screening police candidates, psychologists need to check for abnormal personality traits. Clark, like many police psychologists across the U.S., uses the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2-Restructured Form (MMPI-2-RF).

But the way Clark interprets the written test results may lead to unnecessary rejections, according to three leading experts.

A 2014 study published in the journal “Psychological Assessment” has shown that job applicants, especially for police roles, tend to underreport their problems on the test.

Because of this tendency, the MMPI test’s interpretive manual says a psychologist should not reject or “invalidate” a candidate based on certain scores alone, but should weigh other factors — like the background check and the in-person interview — to determine if a candidate is psychologically sound.

The majority of police-screening psychologists don’t reject candidates based on their written tests alone, said Michael Roberts, a pioneer in the field of police psychology who runs a screening company in California.

“This finding does not or should not result in an automatic rejection,” he said.

But Clark has continued to rule out candidates based on the written tests, according to agency records. This is a stage of the psychological evaluation where candidates of color are disqualified at a disproportionate rate, according to agency data.

Clark said in an email he needs data produced by the MMPI-2-RF to rule out candidates with psychological problems, and can’t recommend applicants “in my professional opinion” without it.

Slow to reform

By the time Kathleena Ly took the evaluation in 2019, not much had changed.

Despite calls for reform, the Deloitte report published this year found that WSP “ultimately did not make substantive changes despite relatively low-cost solutions available.”

The most recent class of WSP candidates Deloitte examined earlier this year had a failure rate of 38%, the same rate as 2016. In the most recent national survey of police psychologists, the average failure rate was 16%.

Ly hopes the WSP will overhaul the psychological evaluation process: “Just having another psychologist — even a female psychologist — would make a huge difference.”

Personally, she has written off a career in law enforcement.

Reprinted with permission of The Seattle Times.