Trickle-Down Effects From Overcrowded Hospitals: Ambulances Scarce And A House Burns

Listen

The overcrowded hospitals we’ve been telling you about for weeks are having ripple effects out into the community — some you could predict and some which are a little more startling. Take for example a fire that gutted a house in Ocean Shores, expensive airlifts from Leavenworth, Washington, and slow response times for ambulance transports in Portland.

There is no private ambulance service in coastal Grays Harbor County. So, when someone in Ocean Shores calls 911 with cardiac symptoms, a bad leg break or head injury, the fire department takes them to the hospital. Firefighter/EMT Kara McDermott said typically, the closest available hospital is about 30 minutes away in Aberdeen.

“From the time we get dispatched to the time we roll our apparatus back into the bay, it’d be about two hours,” McDermott said. “That means the time to respond, the time on scene, the time it takes to transport them to the hospital.”

But starting early this summer, the close-by hospitals in the county would routinely be “on divert.” That means the emergency room staff tells incoming ambulances to find someplace else to go because they cannot accommodate any more patients aside from last-gasp traumas.

“If we have to travel farther afield — we have to go to Elma, we have to go to Olympia — the transport times balloon significantly, which means we have a crew and an apparatus out of the city for three, four, five, even six hours,” McDermott explained with obvious frustration in her voice.

One evening in June, all the firefighters on duty in Ocean Shores were stuck on ambulance trips out of town. Then a fire broke out in a two-story house.

“That is just our worst nightmare,” McDermott said. “There was a sort of a cobbled-together response, but not the quick, efficient professional response that we train and take so much pride in.”

In a follow-up interview, Ocean Shores Fire Chief Mike Thuirer described how he was left to cover the city alone when the alarm sounded. Thuirer enlisted a retired chief to drive one fire truck with him to the scene, where they found a “fully involved” house fire. Several off-duty Ocean Shores firefighters rushed back to the station to bring a second fire truck about ten minutes later. When further help eventually came from a neighboring rural fire district, the responders were able to contain the blaze to the house in which it started.

Thuirer said the homeowners were away at the time, but their two dogs perished from smoke inhalation, one at the scene and one at a pet hospital later.

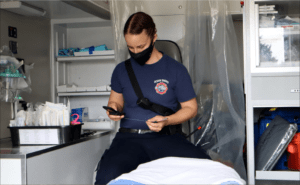

A new accessory in Ocean Shores ambulances is a telephone tree of distant hospital emergency rooms for McDermott to dial if her rig is turned away in nearby Aberdeen, Washington. SOURCE: Tom Banse

This predicament is not limited to the Washington coast. Ambulance crews across the Pacific Northwest are being stretched by longer trips and diversions. The reasons given are similar everywhere: it’s trickle-down from hospitals being full or short on nurses and coping with too many COVID-19 patients.

In July, Thurston County, Washington, notified residents to be prepared for potentially lengthy waits for non-critical ambulance transports. Medic units were being held up at the emergency departments for long durations awaiting a bed to become available. The resulting backlog of patient offloads prevented ambulances from returning to service promptly for new 911 calls.

“We’re not out of the woods yet,” Thurston County Medic One ALS Program Manager Ben Miller-Todd said in an interview Tuesday, after noting recent improvement in the availability of ambulances. He said the county’s primary hospital had streamlined some processes to speed up throughput in the emergency room, which helped. In addition, more staff on the ambulance side were hired.

The same ambulance turnaround delays are now cropping up in the Portland region. In a statement, private ambulance company AMR said its crews are often being kept waiting with their patients at emergency room doors. AMR Operations Manager for Multnomah County Rob McDonald said this is happening multiple times per day because of “an unprecedented number of patients” hospitals are receiving.

In Leavenworth, Washington, the scarcity of ambulances has had costly consequences for families and their insurers when patients needed to be transferred to Seattle for higher level care.

“Twice in (early September) we’ve actually had to transport patients by air,” reported Cascade Medical Center CEO Diane Blake. “Typically, air transport is reserved for those really most urgent, dire cases. These weren’t that, but we didn’t have ground transport.”

Blake added that such helicopter airlifts are “of course, really expensive” and not what the service is meant for. She attributed the shortage in ground transport to ambulances driving long distances to transfer patients, say from Leavenworth to Spokane instead of to the much closer Wenatchee hospital, which is full.

“As we’re doing a great job of finding beds across the state for patients, it’s putting more of a strain on the transport resources. There are times when they are not as available,” Blake said.

People searching for solutions are focusing at the beginning of the trickle-down chain. So said Dr. Steve Mitchell, who monitors hospital capacity statewide at the Washington Medical Coordination Center in Seattle.

“Our opinion has been the best way to get those ambulances back in the streets is to try to offload all of the hospitals which are severely impacted,” Mitchell said Monday.

Mitchell said one way his coordination center is trying to reduce the overload is by helping overburdened hospitals more quickly move patients who are suitable to receive further treatment in the community at places such as long-term care facilities. Separately, labor unions for nurses said hospital management should consider retention bonuses and better pay for long hours to ensure adequate caregiver staffing.

Mitchell also echoed the familiar guidance that everyone can do their part to help by continuing to wear their mask and get vaccinated, if not already.

Gov. Jay Inslee sent a letter to the federal government last week requesting 1,200 Defense Department clinical and hospital support personnel be sent to Washington state to temporarily shore up staffing in overwhelmed medical centers. The governor’s spokesman said Monday the state had not yet received a response.

During a briefing hosted by the Washington State Hospital Association on Monday, Mitchell said he thought the stress on the medical system was easing slightly after observing a modest dip in new hospitalizations, but that conditions still posed a significant problem especially along the border with Idaho.

The Oregon House Health Care Committee has scheduled a meeting on Thursday to discuss the health care “workforce crisis” with testimony to be provided by the Oregon Nurses Association and Oregon Association of Hospitals and Health Systems.

Related Stories:

In one Idaho town, nurse-midwives stepping up as hospital struggles to recruit obstetricians

Rural communities are struggling to bring in obstetricians. Nurse-midwives are helping to fill the gap, but more is still needed to ensure long-term health care access

COVID-19, 5 years later: Reflections on the scars we carry, and resilience in unprecedented times

NWPB caught up with local residents and doctors to talk about how they’ve moved forward following the COVID-19 pandemic. They spoke about how the experience changed them and wisdom they’ve gleaned along the way. These are their reflections.

Proposed Medicaid cuts threaten rural healthcare in Washington, experts warn

CVCH East Wenatchee behavioral medicine building, right, approaches completion with mostly interior work to be finished Tuesday, Oct. 29, in East Wenatchee. (Credit: Jacob Ford / Wenatchee World) Listen (Runtime