Past As Prologue: The Complicated Relationship Between Indian Scouts And The U.S. Government

Listen

NOTE: The following essay and its audio component are part of an ongoing series produced in conjunction with the Washington State University history department. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the author.

BY RYAN BOOTH

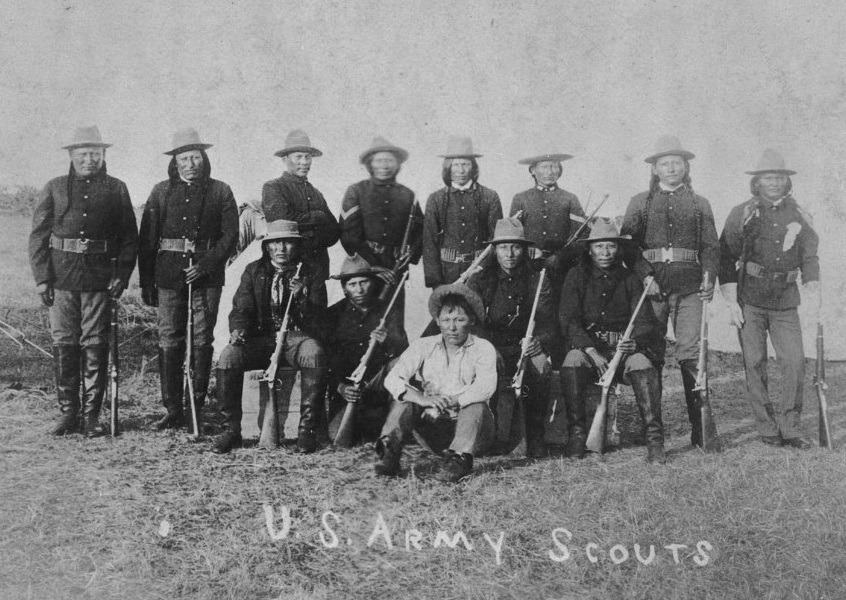

When we think of the U.S. West, we think of the typical relationship between European settlers and indigenous groups is as adversaries. In popular fiction the stereotype of “cowboys and Indians” persists even today. However, Indian Scouts who served in the U.S. Army from 1866 to 1947 demonstrate that this relationship was far more complicated.

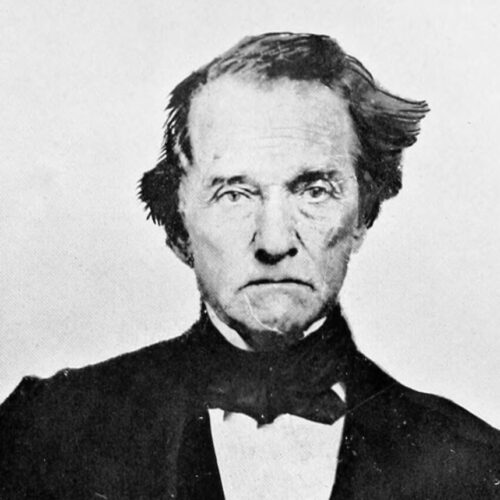

Ryan W. Booth, ABD, is a PhD candidate in the history of the American West at Washington State University’s Vancouver campus. Courtesy of Ryan Booth

For example: James Tangled Yellow Hair. When he was 23, Tangled Yellow Hair enlisted in a band of Northern Cheyenne scouts based at Fort Keogh in Montana. As an old man, Tangled Yellow Hair remembered hearing tribal elders praise Bear Shirt—one of the nicknames for General Nelson Miles—who had encouraged the Cheyenne to become scouts. Yellow Hair wanted the same glory. Private Tangled Yellow Hair ended up joining the U.S. Indian Scouts in time to participate in the 1890 Wounded Knee Massacre. As they dug graves for the unarmed Lakota men, women and children, he remarked that this was “not at all brave on the part of the soldiers.” Yet he continued to wear the Army blue uniform in an effort to stave off hunger, poverty, and the lingering possibility of being labelled “hostile” to the U.S. government.

Private Tangled Yellow Hair ended up joining the U.S. Indian Scouts in time to participate in the 1890 Wounded Knee Massacre. Photo Public Domain

Tangled Yellow Hair was far from alone. Wooden Leg, Lone Wolf, Alchesay, Yuma William “Bill” Rowdy, Sinew Riley, and for a time even Crazy Horse were also Scouts. Yes, that Crazy Horse, the one who fought Colonel George Custer at the Battle of Little Bighorn in 1876, but later served as a U.S. Indian Scout in 1877.

These Indian Scouts provided crucial intelligence about their foes, the so-called “hostile” Indians across the U.S. West. They performed many tasks for the Army from acting as interpreters to guarding the transcontinental railroad crews to chasing deserters to keeping order on reservations. They became indispensable soldiers in the Army’s role as “constables on the frontier.” Army officers such as General George Crook to author-artists such as Frederic Remington noted the important role that U.S. Indian Scouts played in the U.S.-Indian Wars, but over time those roles were lost and buried. When they were mentioned, they became generic soldiers mentioned only as “the scouts” did this or the “Indian Scouts” moved over there. Understanding them as individuals helps to restore their humanity.

Scouts like James Tangled Yellow Hair also paved a way for future generations of Native people who served in uniform, who, like him, had a variety of motives and experiences. Like others in the past and today, people join the military because they see others doing it. They are willing to fight to the death because of the person next to them, not necessarily for high ideals. For at least some Indian Scouts, service was just that simple. They saw service as a way out of some incredibly bad options in the late 1800s and early 1900s. For sixteen scouts, their actions in battle led to the Medal of Honor, the highest and most prestigious U.S. military decoration.

Richard Wooden Leg holding Custer rifle. Wooden Leg has braided hair and wearing a handkerchief around his neck. Horse and hills in background. CREDIT: Public Domain

When we think about the U.S. West, we need to remember this complexity, and that Native Americans —then as now — are a diverse group of individuals who have a variety of experiences, motives and goals. It’s past time to see them as simply stereotypical caricatures, and as complex human beings.

Related Stories:

Past As Prologue: Gendered Epithets In Pacific Northwest Politics And Beyond

Past as Prologue essay about gendered epithets in Pacific Northwest politics and beyond.

Past As Prologue: The Non-Coastal Inland Northwest’s Big Ties To The Ocean Shipping Industry

In this Past as Prologue essay, WSU Professor Karen Phoenix explains the history of the shipping container and its Spokane ties.

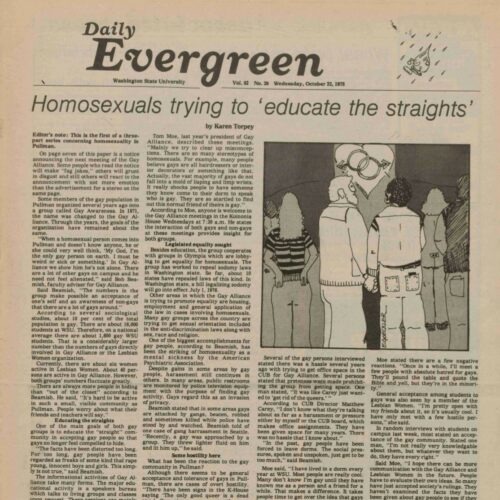

Past As Prologue: Rural Places Are Queer Places And The History Of WSU’s LGBTQ Awareness

What the struggle over recognition for WSU’s Gay Awareness student group shows is some of the similarities between rural and urban LGBTQ rights. Rural areas — especially college towns like Pullman or Moscow — are also queer places. People in cities who were against gay rights used the same tactic as those in Pullman—the public-referendum—to deny housing or employment equality to LGBTQ people.