A Wolf In Northeastern Washington Was Killed Illegally. Here’s Why It’s A Big Deal

BY HANNAH WEINBERGER / CROSSCUT

When wolf biologist Trent Roussin first saw the gray wolf on May 26 in the Sheep Creek area of Washington’s Stevens County, it wasn’t immediately apparent that she had been shot. The wolf was lying on the ground miles behind a locked gate; it was quiet, Roussin says, and not particularly messy or bloody. When he and his colleagues realized she had been poached, he wasn’t surprised. But he was disappointed.

“It’s really a bummer, is the first thing you think,” says Roussin, who works at the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. State-endangered gray wolves, once extirpated from the area, started recovering in Washington in 2008. Apex predators like wolves help keep forest populations of deer and small predators like coyotes in check. But with increasing overlaps between ranching and wolf territory, many people in Eastern Washington see the wolves as headaches at best and threats to life and business at worst.

“We can definitely live with wolves, but we think right now we have an oversaturation of them,” says Scott Nielsen, president of the Stevens County Cattlemen’s Association. “They’re not dispersing as fast as we would like.”

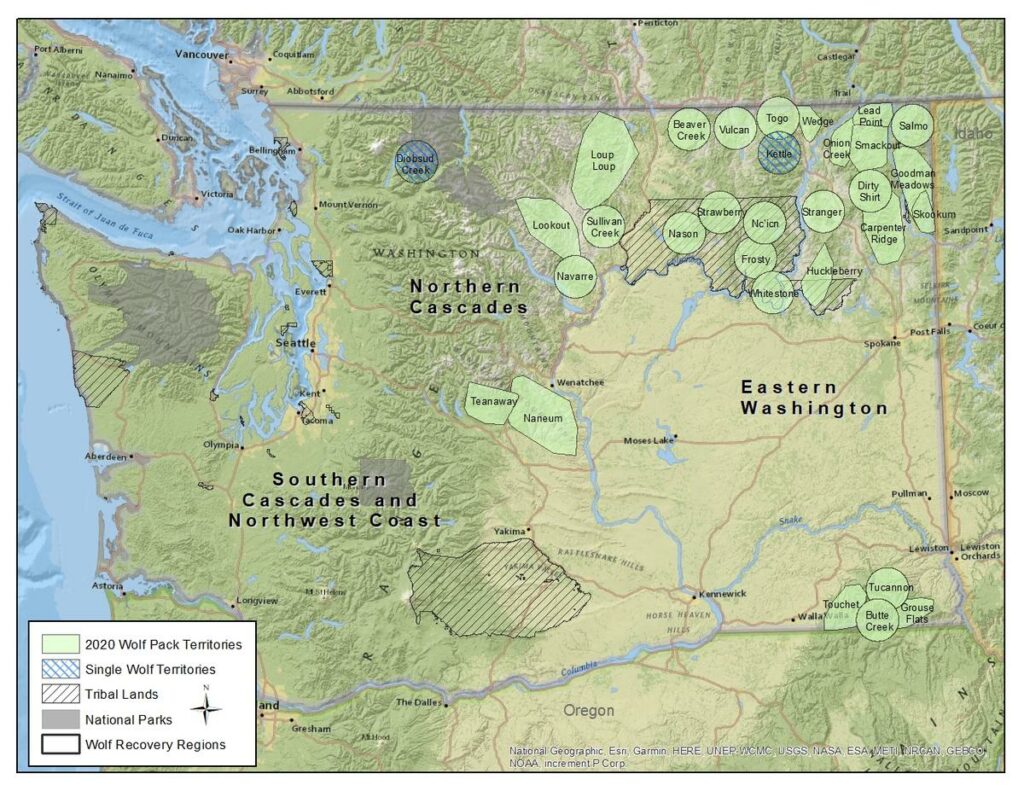

At least seven wolf packs attacked livestock in 2020. Washington saw at least 12 wolf poachings between 2010 and 2018, with the latest known incident in May 2019 in Stevens County. As of April, the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife estimates that there are at least 178 wolves spread across 29 packs in the state, the majority of which are in Eastern Washington; that’s up from an estimated 145 wolves across 26 packs in 2019.

A sign on the side of trailer in Stevens County, Washington, near Chewelah off U.S. Highway 395 prompts people to report “dangerous predators” like cougars and wolves. CREDIT: Scott Leadingham/NWPB

Wolf poachers go mostly undiscovered — but that hasn’t stopped nonprofit organizations from putting up significant cash rewards for information about these incidents. While rewards generally don’t lead to convictions, Defenders of Wildlife’s Gwen Dobbs says reward offers in cases of wildlife poaching can help raise public awareness, “hopefully serving as a deterrent against potential future incidents, even if a reward does not directly lead to a conviction.”

Department of Fish and Wildlife wolf coordinator Julia Smith says the public is key to helping understand when and why these killings happen. “Even if we don’t ever find the person who did it, at least we were able to document and understand what happened here in this particular area,” she says.

The increasing size of the award — $15,000 for information related to the gray wolf Roussin found — doesn’t necessarily indicate anything about what the loss of one wolf means to the pack, to wolf conservation or to ecosystems. The true value of one wolf, those closest to the issue say, depends upon the context in which the loss happens and the scope in which you consider it.

Pack impacts

On a pack level, losing one wolf can seriously threaten the pack’s future. The wolf poached in May wasn’t just any wolf. She was a breeding female in the Wedge Pack, a small pack still establishing itself. After a series of livestock predations in 2012, Washington state killed most, if not all, of the pack, says Paula Swedeen, policy director of Conservation Northwest. New wolves colonized the area within a year or two, and things were quiet until last year, when members of the pack were lethally removed after again killing cattle. According to the 2020 annual population survey, the pack had a minimum count of two wolves.

Given the time of year, it’s likely that the wolf had had pups within the past few months, and it’s also likely they won’t survive. “Wolf pups have a high level of mortality anyway,” Smith says. The pups have roughly 50% chance of surviving their first year, even with their mothers present. The pack won’t be able to produce new pups until next spring at the earliest.

When the Smackout Pack lost a female breeder in 2015, her partner stepped in to care for the pups, Swedeen says. When the state culled a breeding female in the Huckleberry Pack during a lethal removal in August 2014, it was late enough in the season that pups were likely old enough to make it on their own.

For small packs, losing breeding females can mean the pack not only loses pups, but dissolves entirely.

In a recent research paper exploring breeder loss to packs in Denali National Park, co-written by University of Washington researchers, breeder loss preceded pack dissolution in 77% of cases.

“Breeding females tend to be the glue of the pack,” Roussin says. “On a local scale, if we lose just one breeding female in a certain recovery region, that can be a huge deal.” He points to the south Cascades, where there currently aren’t any breeding pairs.

Members of dissolved packs may stay in the area and wait for another breeding female to join them, or seek out existing members of the pack to start breeding the next season. They may also disperse in search of other packs, or to find new territory and start their own.

Starting new packs can be problematic in Eastern Washington, which is already saturated with wolves. Any direction they venture, the wolves are liable to run into other packs — and wolves are territorial so they could also get killed by other wolves, Roussin said.

Population impacts

Zooming out to the population level, though, the impacts of losing one wolf aren’t as substantial to recovery. “The research we’ve done shows wolf populations are pretty resilient to harvests and not as fragile as a lot of the conservation community believes them to be,” says Dr. Laura Prugh, a professor of wildlife ecology at the University of Washington.

Prugh, who helped lead the research in Denali National Park in Alaska, has found that where wolves are plentiful, there’s no population-level impact when you remove a wolf.

Denali hasn’t experienced extirpation, Prugh says, “so it’s possible that the removal of [the poached breeding female] wolf could slow down the recovery a bit.”

However, when the Department of Fish and Wildlife removed wolves from the Wedge Pack last summer, within about two months Roussin started hearing reports of wolves recolonizing the area. “It just goes to show that if a pack blinks out for any reason at the stage of recovery that we’re in, at least in the northeast part of the state, those territories usually fill back in fairly quickly,” he says.

While the wolf population is resilient to losing one wolf, packs disbanded in their wake can affect the way statewide recovery unfolds in space and time.

The state is already behind on its recovery goal of having packs and breeding pairs established in all three recovery zones, initially projected to be met in 2021. Researchers say dispersing wolves may not explore new territories and where there are fewer pups, there are fewer opportunities to establish new packs.

“Folks who want to see wolves removed from the state endangered species list should be vehemently opposing poaching, which is just going to prolong reaching their statewide recovery objectives,” says Zoe Hanley, Defenders of Wildlife’s Northwest representative, who works with communities on the ground to further human-wildlife coexistence and conservation goals.

Nielsen of the Stevens County Cattlemen’s Association agrees. The ranching community, he says, was content to leave alone the wolf poached in May. As far as the community knows, the wolf wasn’t predating on livestock. He acknowledged that breeding females are essential to increasing the population, and young wolves leave home to find new territory. “One of our goals is to get them to numbers [and distribution] where they can be delisted,” he says.

UW’s Prugh says researchers are still exploring how many wolves are needed to maintain the ecosystem benefits they bring to landscapes.

“Having wolves present is one thing, but having them perform their ecological function is another, and [how many wolves you need] is a real open question right now,” she says.

Because wolves target primarily the most vulnerable animals as prey, Defender of Wildlife’s Hanley says, they can help those prey populations remain healthier and more vigorous. Wolf predation also regulates prey distribution and group size, which can impact the diversity of that entire ecosystem over time. “It’s just so important to maintain wolves and other apex predators, so that we can ensure ecosystem health during this crazy time of climate change,” Hanley says.

Human impacts

Washingtonians may feel the loss of one wolf more deeply than the wolf population itself, conservationists say.

“The wolves will recover. But it’s just unfortunate from a human perspective that folks are out there doing this,” Roussin says. Wolves die all the time: The way that this wolf died is what’s making it an issue for people.

Wolf advocates were already primed to take the May poaching hard. The state-led use of lethal removal of wolves in the Wedge Pack last summer is a sticking point for those who think any form of killing is wrong, and the pack had only just started reestablishing at the time of this poaching. A federal-level decision to delist gray wolves from the federal endangered species list in January exacerbated hard feelings.

“There’s a significant segment of the population, I think, that cares about wolves as individual animals. And it’s so heartbreaking to think about the fact that someone so dislikes those animals that they would go out of their way to kill one, especially when the population is still recovering and especially when it’s a protected species,” Conservation Northwest’s Swedeen says. “And anytime that vulnerable young animals die, that’s also very upsetting.”

Prugh says she’s amazed by the impact one poaching can have on the human political ecosystem. “They just evoke such a strong emotional response, I think, that’s really disproportionate to their actual threat or their actual benefit,” Prugh says. “I feel like in the human realm they’ve almost become just another thing to fight over, and I’ve definitely heard people say things like, ‘Well, wolves are Democrats.’ They’ve become very symbolic of the larger polarization in our society.”

Omens of serious recovery setbacks

Experts within both conservation groups and the Department of Fish and Wildlife say human-wolf relations have been trending positively since recovery started, despite a few incidences of poaching and discontent within ranching communities. Breeding pairs have increased each year since Washington started counting them. “There’s a lot of folks who might want to paint [conservation] like it’s doom and gloom, but to me from a purely biological perspective we see our wolf population trending in the direction that we want it to go… and they’re largely coming back on their own,” says Smith, the Department of Fish and Wildlife wolf coordinator.

“Most of the wolves are good wolves, and they’re not out there depredating. And [the poached wolf] wasn’t one of the bad ones,” Nielsen of the rancher association says, noting that the Wedge Pack had been pretty well-behaved up until last year. “So as long as they’re behaving themselves, for ranchers, I don’t think there’s a negative impact.”

To be concerned for recovery at the population level, there would have to be pretty severe mortality, about 30% — or 50 to 60 wolves — based on recovery developments seen elsewhere, Roussin says. Smith says that last year there was a mortality rate of 9%; the year before, it was 14%. Lethal removal by the state has averaged 3% of the population each year, with the most removal occurring in 2012 at 14% of the minimum population count. Poaching hasn’t gotten to a point where it would affect population-level recovery.

“After living alongside wolves for 10 years now, I think a lot of the myths are falling away,” Roussin says of living with wolves. Livestock producers who used to talk about killing wolves, he says, realize that taking one won’t do much to the population as a whole. “Another wolf is going to be right back in there, within months or shorter,… They realize they’re not going to be able to kill all the wolves to solve the problems they think they have.”

Nielsen agrees that while tensions remain, coexisting with wolves — and interacting with the state Department of FIsh and Wildlife — has been generally positive for ranchers since recovery started. But, while there’s a lower percentage of wolves creating problems, there are more wolves out there, and the problems seem to continue, he says, despite most ranchers investing in nonlethal deterrence tools. Nielsen doesn’t condone poaching, but says poaching likely happens when people feel frustrated about how wolves are being managed.

“I know social tolerance cuts two ways, but it’s not acceptable to have them eating our livestock. And we think part of why they don’t move on is because they have an abundant food supply here. And unfortunately part of that food supply is our livestock,” Nielsen says.

Visit crosscut.com/donate to support nonprofit, freely distributed, local journalism.