Corporate Landlord Evicts Black Renters At Far Higher Rates Than Whites, Report Finds

BY CHRIS ARNOLD

Katrina Chism was frightened and confused. She’d been renting the same house in Atlanta for three years. She’s a single mom with a teenage son. But then she lost her customer service job during the coronavirus pandemic and fell a month behind on her rent.

“I remember going to the door and the sheriff standing there,” Chism says. “It scared me because I didn’t know why he was at my house.”

The reason: Her landlord had filed an eviction case against her.

“Once you get that eviction, no one’s going to want you to rent from them,” Chism says. “I don’t want to be in a homeless situation.”

Getting evicted can send people into a downward financial spiral. During the pandemic, there has been the added danger of catching or spreading the coronavirus.

But that hasn’t stopped Chism’s landlord, a company owned by the private equity investment firm Pretium Partners, from filing what critics say is a lot of eviction cases against people during the pandemic.

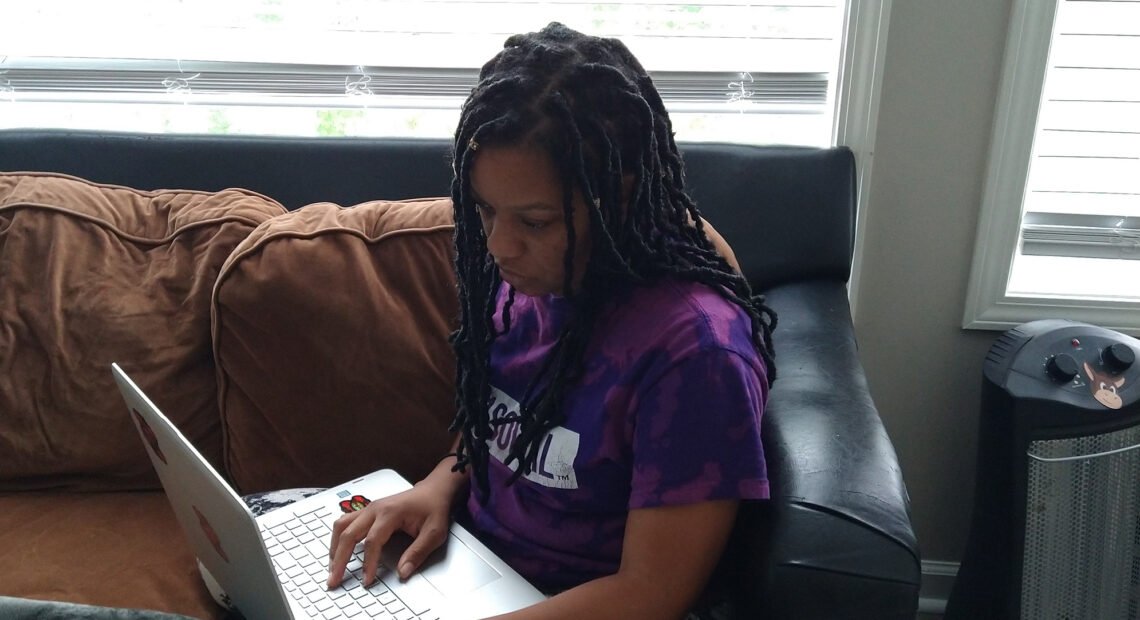

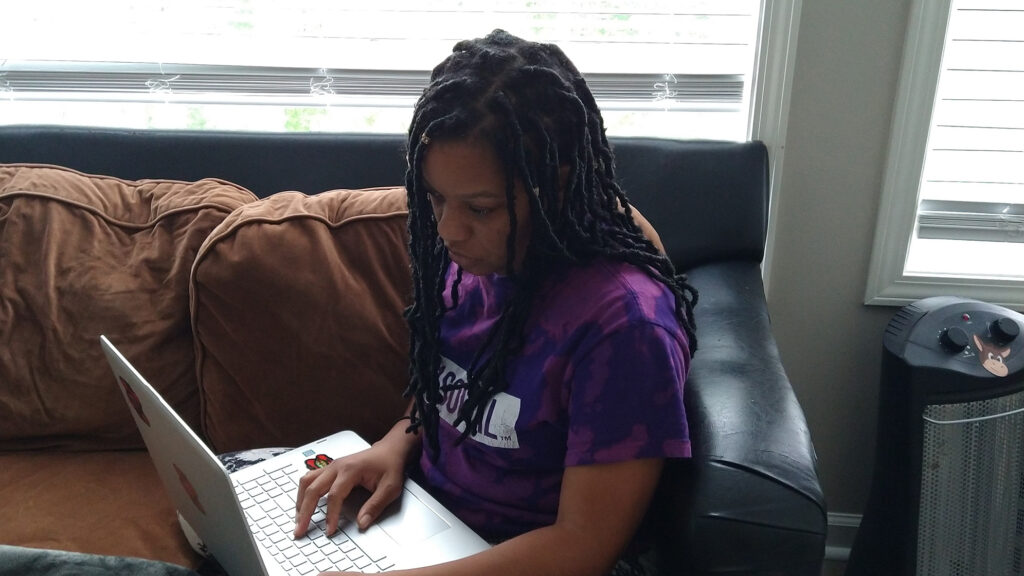

Katrina Chism’s landlord filed an eviction case against her after she lost her job during the coronavirus pandemic and fell a month behind on the rent. “Once you get that eviction, no one’s going to want you to rent from them,” Chism, 41, says. Katrina Chism

“The company has filed to evict more than a thousand residents since last September,” says Jim Baker, the executive director of the Private Equity Stakeholder Project. It’s a nonprofit advocacy group that describes itself as supporting workers, communities and others impacted by private equity investment firms.

The group has been tracking eviction filings by corporate landlords and, in a report on Pretium, says it has found a racial disparity.

According to the report, since the beginning of the year, “they’re filing to evict residents at rates four times as high in majority-Black counties,” says Baker.

The group looked at four counties where Pretium owns hundreds of rental homes in each, and it compared two mostly Black counties in Georgia with two mostly white counties in Florida. The median incomes in the counties are similar.

But the report found that in the white counties, Pretium has been filing for eviction against about 2% of the people renting those homes.

“By comparison, they filed to evict 10% to 12% of their residents in majority-Black counties in Georgia,” says Baker. “It’s incredibly disturbing.”

Pretium declined an interview but said in a statement that the report is misleading and makes “baseless assertions.” The company says its property managers “work with residents and seek to avoid eviction and have added more than a dozen employees to assist residents during this unprecedented pandemic.”

The company also says it has waived millions of dollars in late rent and secured more than $10 million in government rental-assistance money for residents.

The report doesn’t allege any discriminatory intent on the part of the company.

“There’s nothing here about racial disparities in eviction that I find surprising,” says Peter Hepburn, a researcher with the Eviction Lab at Princeton University. He has read the report and says the disparate impact on Black renters goes far beyond any one company.

Hepburn recently published a study looking at millions of court records of eviction cases across 39 states. The data reaches back before the pandemic.

“Nationwide, on average, we’re seeing eviction filing rates against Black renters that are about twice as high as what we see for white renters,” Hepburn says. He says there are many reasons for that, some being economic.

“We know that the Black renters have lower incomes,” Hepburn says. “They have less stable employment as well, they have less in savings and they’re less able to call on family ties to provide financial support in the event of an emergency.”

But Hepburn says all that still doesn’t explain the whole story of why Black renters nationally are twice as likely to have eviction cases filed against them.

“I think there’s reason to suspect that landlords may be quicker to file for eviction against a Black tenant who’s fallen behind on rent than a white tenant,” says Hepburn.

It’s unclear why the report on Pretium’s eviction filings apparently found an even higher disparity — more than four times the rate in mostly Black counties as in mostly white counties. But Hepburn says that’s not unprecedented. He found similar disparities when examining just a few counties around the country.

Pretium says it provides “equal rental opportunities and support to all of our residents.” The company says it does not track the race, gender or ethnicity of residents.

Still, Baker, whose group did the report on Pretium, says the company appears to have the resources to be a lot more flexible with renters during a pandemic.

“Pretium Partners is not a mom-and-pop landlord,” Baker says. “They’re run by a guy named Don Mullen, who used to work for Goldman Sachs,” Baker says. “He just bought a $20 million mansion in Miami.”

He says the privately held company has billions of dollars under management and owns 55,000 homes, making it the second-largest owner of single-family rental homes in the United States.

Pretium declined repeated requests for an interview with Mullen or another company executive.

Baker says his group looked at other large corporate landlords too. “We’ve actually found that there are some quite large landlords that have held off on evicting residents,” he says.

Since September, an order from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has aimed to stop evictions for renters with no place to go. But renters have to know about that and take steps to be protected. Pretium says it’s complying with the CDC rules.

In Chism’s case, after getting that eviction filing notice in January, she says she scrambled, found a temporary job and managed to catch up on the rent.

“I worked my butt off and I borrowed money and I saved everything that I could,” Chism says. But when the temp job ended, she fell behind again.

Chism applied for federal rental assistance money. And she got it. But she and her lawyer say the company refused to take it. Pretium disputes that. She says the company told her that her lease was about to end and she had to leave or get evicted.

The company offered to forgive the back rent and fees she owed, but only if she and her son moved out right away.

“Yes, it’s been extremely exhausting,” Chism says. “I literally have things thrown in boxes.”

Chism spoke to NPR again as she was packing and moving. She managed to find a place to rent. But she says it’s $400 more a month. And the house is an hour away, so her son has to switch schools.

“He just gave me that look like, ‘Mom, really?’ ” she says. ” ‘Now I’ve got to stop and start all over again?’ ” Chism says, though she is glad the company says it will dismiss her eviction case.

Meanwhile, Baker says Pretium has been filing more eviction cases since his report. He says since the start of the year, the company has now filed to evict nearly 20% of its residents in those mostly Black counties in Georgia.