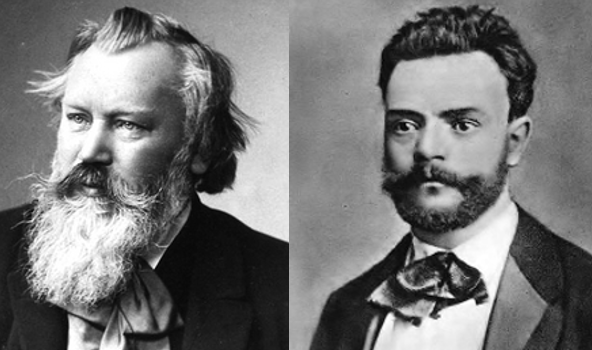

Passing The Baton: Brahms And Dvorak

Was Johannes Brahms as sweet and comforting as the lullaby that bears his name? Actually, as conductor Manfred Honeck told the New York Times, “There was nothing cozy about Brahms.”

He never had students in the formal sense. Brahms’s manner was described as “not encouraging,” when younger composers would beg for his attentions. But Antonin Dvorak didn’t have to beg.

The two of them were very different: the sweet and kindly Dvorak, nurtured from childhood into a musical life; a family man, eking out a living as an orchestral violist and piano teacher, his compositions popular among provincial audiences.

Brahms, on the contrary, was a solitary but well-connected man, whose music filled concert halls from Vienna to London and beyond. Although incredibly well respected, Brahms was considered conservative and critical of his fellow composers – which helped with his “not encouraging” reputation.

We know Brahms made a tidy fortune from his rhythmically-tricky Hungarian dances. So it’s no surprise that Brahms did a double take when confronted with the rhythmic delights and a sheaf of compositions by the relatively obscure Dvorak. The occasion was an 1877 competition for prize money. Brahms had grumpily agreed to sit on the panel of judges.

Brahms’s enthusiasm for Dvorak’s work not only granted the prize money to the young Bohemian, but also led to a deep and lasting friendship between the two: Brahms became Dvorak’s mentor, not only in composition techniques, but also in the business of success. It was Brahms that helped Dvorak connect with the the music critic Louis Ehlert, whose essay launched Dvorak into international stardom.

Brahms offered Dvorak his entire estate if he would transplant to Vienna, but the small-town life in Bohemia was the one Dvorak loved best.

Dvorak came to Vienna to pay Brahms an end-of-life visit, and then attended his funeral. Soon after, Dvorak was named to the jury for the same composers’ competition that, years before, had earned him the attentions, and the support, of Johannes Brahms.

Related Stories:

Dedicate Classical Music To A Special Someone This Valentine’s Day

Music can express and inspire so many emotions. That makes it a perfect way–a “heartfelt” way–for you to show your love and appreciation to someone who plays an important role in your life.

Vote For Your Favorite Music In NWPB’s Classical Countdown

What is your favorite symphonic movie score? Your favorite aria or overture? Whether it’s a well-known composition by Bach or Beethoven, or a hidden gem by a lesser-known composer, NWPB wants to know what pieces resonate with you.

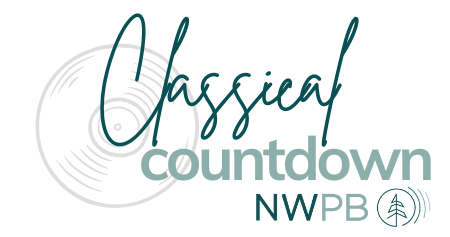

Women’s History Music Moment: Bach’s Daughters

You’ve heard so much about the sons of Johann Sebastian Bach, but there were daughters, too.

Bach was 23, and his wife Maria Barbara was 24, when the first of their children was born. They named her Catherina Dorothea. CD grew into a singer, and helped out in her father’s music work. Fifteen years passed, her mother died, her father remarried, and finally, CD Bach acquired a sister: Cristina Sophia Henrietta, daughter of Johann Sebastian and Anna Magdalena Bach. CSH died at the age of three, just as another sister, Elizabeth Juliana Frederica, was born. EJF Bach would grow up to marry one of her father’s students.