Confused By CDC’s Latest Mask Guidance? Here’s What We’ve Learned

WATCH: CDC Director On Mask Guidance

(Story continues below video)

BY SELENA SIMMONS DUFFINS / NPR

If you’re fully vaccinated against COVID-19 (as in, you’ve gotten all your shots and waited two weeks), the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced Thursday, you can mostly go ahead and stop wearing your mask and stop social distancing — inside and out.

“Fully vaccinated people can resume activities without wearing a mask or physically distancing, except where required by federal, state, local, tribal or territorial laws, rules and regulations, including local business and workplace guidance,” the CDC now says. (There are some important exceptions we’ll get into below.)

The shift in guidance was a dramatic reversal from the country’s top public health agency, which has been criticized for being too conservative (and convoluted) in its earlier guidelines for those who are vaccinated. The latest changes have left a lot of people with a lot of questions, which NPR’s science, health and education reporters are here to answer.

Was this shift in the guidelines a surprise?

Yes, many leaders in the public health world say they didn’t see the loosening of recommended restrictions coming so quickly, and some were dismayed.

Dr. Leana Wen, an emergency physician and public health professor at George Washington University, called the change “stunning” in a Friday interview with NPR. “CDC seems to have gone from one extreme of overcaution to another of basically throwing caution out the window.”

“If the United States had the vaccination rates of Black communities (about 27%), I don’t think the CDC would have changed the masking guidelines,” Dr. Rhea Boyd, a pediatrician and public health advocate in the Bay Area, wrote on Twitter. “We should change guidelines when it is reasonable and safe for the populations made MOST vulnerable, not for those who are the least.”

Others were more supportive. “All of us who work in public health and in medicine have a very high level of respect and confidence [in] the Centers for Disease Control,” Dr. Marcus Plescia, chief medical officer of the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, told NPR on Friday. “So when they say, ‘Now’s the time’ and the data suggests that this is the safe and effective thing to do, that means a lot to many of us.”

— Selena Simmons-Duffin, health reporter

Was the change based on science?

CDC says that yes, this decision was based on the current state of the pandemic in the U.S., along with evidence that vaccines are extremely effective in the real world. “That science, in conjunction with all of the epidemiologic data that we have, really says now is the moment,” CDC Director Rochelle Walensky told NPR on Thursday.

Walensky notes that the number of cases, hospitalizations and deaths in the United States have declined significantly in recent weeks. That suggests that because of vaccination — and because some people are immune because of previous infection with the coronavirus — the pandemic is gradually coming under control.

Walensky has also cited several recent studies of health care workers as evidence that vaccines provide excellent protection against disease. One CDC study published Friday found that across 33 sites, vaccinated health care personnel were much less likely to get sick with COVID-19 than those who were unvaccinated.

After the CDC shifted this week to less restrictive mask guidance for people who have been fully vaccinated against COVID-19, some leaders in the public health world felt blindsided. While some people rejoiced, others say they feel the change has come too soon. CREDIT: Ben Hasty/MediaNews Group via Getty Images

Another recent study conducted at a major medical center in Israel followed about 5,500 fully vaccinated workers for two months. Of those, just eight developed any COVID-19 symptoms, such as fevers or headaches. Another 19 tested positive for the virus even though they had no symptoms. This rate of infection was significantly higher for workers who choose to not be vaccinated. It’s hard to compare that very low rate of infection directly with the risk to the general public. These workers were at much higher risk for infection because they worked in a hospital, but they also wore masks, which limited their exposure.

Most people who do get infected despite having been vaccinated are very unlikely to develop serious illness, the evidence suggests. Most have no symptoms at all, or milder symptoms. However, these so-called “breakthrough infections” have occasionally resulted in hospitalizations and deaths, so the risk is not zero.

“There are those people who don’t want to take that bit of a risk,” Dr. Anthony Fauci, President Biden’s chief medical adviser, said on Thursday in the press briefing announcing the new guidelines. Those people may decide to continue wearing masks, he said, “and there’s nothing wrong with that, and they shouldn’t be criticized.”

— Richard Harris, science correspondent

Does CDC’s announcement change my local rules?

Not automatically. The public health system in the United States is decentralized. CDC doesn’t run or oversee and can’t overrule your local or state health department — it just provides support, such as partial funding and guidance. You’ll still need to check the local rules where you live to see how they’ve changed (if they have) in response to this week’s shift in the CDC’s guidance — here is an NPR roundup of recent state responses to the news.

Plescia of the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials tells NPR that “in states or local situations where there are already laws or regulations about mask wearing, we’ll have to have a look at those laws and regulations and see how we might change them based on this new science and this new announcement.”

For now, when you leave home, it makes sense to bring a mask with you in case the place you’re going still has a “mask required” sign on the door.

— Selena Simmons-Duffin, health reporter

What about going to the grocery store? Or the office?

Whether you need to wear a mask indoors in public venues will depend on local mandates and guidelines, as well as businesses, which make their own operating decisions. CDC’s general guidance for businesses hasn’t yet been updated since this week’s change of recommendation regarding masking for people who have been vaccinated.

Most legal experts agree employers can require vaccination of their employees returning to the workplace. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission reaffirmed that position. But the majority of employers aren’t going so far as to require shots. According to a February survey by the Society for Human Resource Management, 60% of employers are not considering a vaccine mandate (35% are still undecided). It is legal for employers to ask to verify vaccination by checking, for example, a worker’s vaccination card — so long as they are not requesting other medical information that may violate the employee’s privacy.

At the same time, employers also have an obligation to maintain a safe workplace, which can get especially tricky for those who interact with members of the public who may or may not be vaccinated. Whether employers will continue to require masking in their workplaces may depend on a range of factors like local public health regulations, whether that employer has a vaccine mandate (and therefore only vaccinated employees are on site) or whether they have enough space in the facility to distance those who are unvaccinated.

To make things more complicated: Because there are also anti-discrimination laws to take into consideration, employers will also need to accommodate workers who don’t get vaccinated for medical or religious reasons. That means employers need to enforce policies uniformly for all similarly situated employees.

Some settings should still require masks even for fully vaccinated people, according to the new guidelines, including in correctional facilities and homeless shelters, and for staff, patients and visitors in health care settings.

“Locations such as health care facilities will continue to follow their specific infection control recommendations,” CDC Director Walensky said when announcing the new guidelines.

— Yuki Noguchi, consumer health correspondent

What about schools?

Schools are a bit different from businesses, especially since kids under age 12 are not yet eligible to be vaccinated.

It is unclear what impact this will have on teachers, staff and students in the near term. CDC has not yet revised its K-12 schools safety guidance. “What we really need to do now as an agency is comb all of our guidance […] for schools and for camps and for child care centers and for all of the guidance that we have out there and apply the guidance that we have for individuals — vaccinated individuals to that,” Walensky told NPR.

At least one district did move quickly Thursday to announce changes to its own in-school safety policies. “In accordance with the new [CDC] guidance, Cobb Schools will no longer require fully vaccinated individuals to wear a mask,” wrote Chris Ragsdale, the superintendent of schools in Cobb County, Ga. “I would also like to make clear that any individual wishing to continue wearing a mask while attending school and/or school events should feel free to do so.”

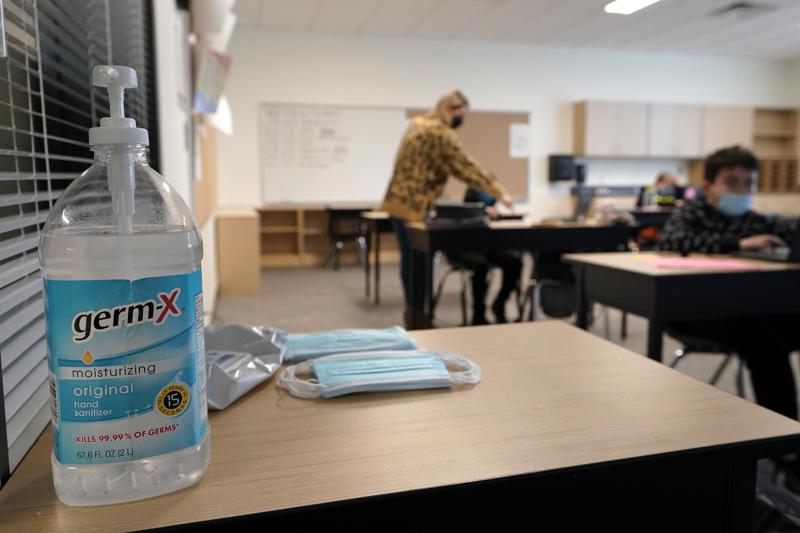

File photo. Hand sanitizer, wipes, and surgical masks rest on a desk in a fourth-grade classroom at Elk Ridge Elementary School in Buckley, Wash. State authorities said May 13, 2021, all schools in the state must provide full-time, in-person education for students for the 2021-22 school year and that students and staff will still be required to wear masks as a COVID-19 mitigation effort. CREDIT: Ted S. Warren / AP

In some states, masks in schools are already optional. “Whether a child wears a mask in school is a decision that should be left only to a student’s parents,” said South Carolina Gov. Henry McMaster earlier this week as he issued an executive order allowing parents to opt their children out of school-based mask requirements.

That move was excoriated by the Palmetto State Teachers Association. In a statement, the group said, “Many families and staff no longer have a choice for in-person learning if those individuals desire to follow the clear instructions of our public health authorities.”

And Becky Pringle, president of the nation’s largest teachers union, the National Education Association, urged state and district leaders not to scrap in-school masking mandates.

“We know at this point that only a third of adults are vaccinated and no students younger than 16 are vaccinated,” Pringle said Friday in a written statement. “CDC’s key mitigation measures for safe in-person instruction, including wearing masks, should remain in place in schools and institutions of higher education to protect all students and others who are not vaccinated.”

— Cory Turner, education correspondent

How do I know people around me are fully vaccinated?

You don’t. The U.S. federal government has declined to pursue the idea of vaccine passports that would verify someone’s vaccination status as a way of allowing them to follow different sets of rules.

“The government is not now, nor will we be supporting a system that requires Americans to carry a credential,” White House coronavirus response coordinator Jeffrey Zients said in an April press briefing. “There’ll be no federal vaccination database [and] no federal mandate requiring everyone to obtain a single vaccination credential.”

For some, this poses a real problem, says Dr. Leana Wen, a former Baltimore health commissioner and emergency room doctor who has two small children. “If I’m bringing them into the grocery store and now there are people around us who are all maskless, I have no way of knowing if the person breathing on my children and standing very close to them without a mask is unvaccinated,” she said in an interview on NPR’s Morning Edition Friday.

— Selena Simmons-Duffin, health reporter

Speaking of which, I have little kids who are unvaccinated. How does this change our risk?

Many millions of children in the U.S. are unvaccinated — and while adolescents over age 12 just this week became eligible for Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine, it will take two weeks after they get their final dose before they are fully protected.

Children and adolescents can get sick from infection with the coronavirus and they can infect others. And while, in general, their cases tend to be less severe, some children have developed serious complications.

There are also increasing concerns about persistent, long-term effects of the viral infection — such as fatigue, respiratory issues and stomach problems — for some children who get COVID-19. And while most children who catch the coronavirus develop few or no symptoms, they can still, inadvertently, transmit the virus to others.

All of this puts parents of young children in a bind, especially in places where schools are lifting masking requirements. They have to navigate workplaces and schools that may now be changing their rules, without being able to protect their children with vaccination.

Pfizer this week projected that it would be asking the Food and Drug Administration to authorize its COVID-19 vaccine for use in younger kids in September.

In the meantime, CDC advises that unvaccinated “people age 2 and older should wear masks in public settings and when around people who don’t live in their household.”

Dr. Emily Landon, an infectious diseases expert at University of Chicago Medicine, says that fully vaccinated parents of unvaccinated children can safely take off their own masks. But parents might want to keep them on when they’re out in public with those children “in solidarity with our kids, to help them feel like they’re not an outlier and to make sure that we’re setting a good example for them,” Landon says.

— Pien Huang, health reporter

I’m immunocompromised. What about me?

CDC says that if you are immunocompromised — even if you’re fully vaccinated — you should talk to your doctor about what precautions you need to keep taking. That’s because, in this case, even more than others, you can’t assume that vaccination equals protection, says Dr. Brian Boyarsky, a research fellow at Johns Hopkins who has been studying vaccine efficacy in immunocompromised patients.

“These CDC guidelines are largely for people who have normally functioning immune systems,” he says. “The big takeaway so far is we do not yet know the full effectiveness of the vaccines in immunocompromised people.”

The initial vaccine trials didn’t include people who take immunosuppressive drugs, so research underway is trying to fill in the blanks. The evidence so far suggests that the vaccines may be less effective in some immunocompromised people, depending on the medication they take and their medical condition. That includes people who take immunosuppressive medications such as mycophenolate and rituximab to suppress rejection of transplanted organs or to treat certain cancers or rheumatologic conditions.

If you are immunocompromised, it’s important to keep up the masking and physical distancing and to make sure the people around you are fully vaccinated, too, researchers say. “When everyone around you is getting more reckless, you need to get more safe,” says Dr. Dorry Segev, a transplant surgeon and researcher at Johns Hopkins. “Be careful for the time being,” he advises his patients, “because we don’t know enough to flick the switch like the CDC did for everybody else.”

— Maria Godoy, health correspondent

I feel weird about this new guidance. Can I keep wearing a mask?

Of course. “Not everybody’s going to want to shed their mask immediately,” Walensky told NPR on Thursday after the announcement. “I think it’s going to take us a little bit of time to readjust.”

There will likely be confrontations and side looks in all directions as everyone adjusts to the new guidance and starts to put it into practice. There have already been altercations among members of Congress about how best to interpret the advice

— Selena Simmons-Duffin, health reporter

What about on planes, trains and buses? Do I still have to wear a mask there?

Yes, no changes on that front yet. “Right now, we still have the requirement to wear masks when you travel on buses, trains and other forms of public transportation, as well as airports and stations,” CDC Director Rochelle Walensky told NPR on Thursday.

The CDC requires that masks be worn by travelers on all planes, buses, trains and other forms of public transportation traveling into, within or out of the United States and in U.S. transportation hubs such as airports and stations. “The travel guidance is not just CDC’s guidance — it’s a policy, and it’s an interagency policy, so we have to collaborate with other agencies to work through what might change in that policy,” Walensky added.

The Transportation Security Administration sets rules for airports, commercial aircraft, bus companies, and commuter bus and rail systems. The TSA announced two weeks ago that it was extending its mask requirement at airports, on planes and on public transit through Sept. 13.

A TSA spokesperson told NPR on Thursday that no changes to the rules are expected anytime soon.

— Laurel Wamsley, news reporter

Does this mean the pandemic is over?

Certainly not, though it’s a sign that health officials think the U.S. is on the road to emerging from it. Technically, the definition of pandemic is a major disease outbreak that spans multiple countries or continents, and COVID-19 still fits that bill.

Health officials say that disease transmission won’t happen as often in locales that have low levels of the virus circulating, either because people there are behaving in ways that reduce the spread or because many people in the community have become immune — through vaccination or through previous exposure to the virus.

“We live in a large country, heterogeneous, and you’re going to have different rates of vaccination, different levels of infection [in each community],” said Dr. Fauci at a press conference May 5. Outbreaks are still likely to happen in communities with low levels of vaccination, health officials say, if precautions such as masking and physical distancing are not observed by people who haven’t been vaccinated.

“This past year has shown us that this virus can be unpredictable,” Walensky said when announcing the new guidelines. That’s especially true as new more transmissible variants continue to emerge. “If things get worse, there is always a chance we may need to make changes to these recommendations. But we know that the more people who are vaccinated, the less cases we will have and the less chance of a new spike or additional variants emerging.”

Also, although in the U.S., vaccines are widely available, and cases and hospitalizations are declining, this is not the case in many other countries. Each week, more than 5 million people around the world are newly diagnosed with the coronavirus; cases and deaths are spiking in several countries in Southeast Asia and the Western Pacific, including India, Bangladesh, the Philippines, Japan and Malaysia.

— Pien Huang, health reporter

NPR science correspondent Allison Aubrey also contributed to this report.