Cascade Snowpack More Vulnerable To Climate Change Than Inland Neighbors, Study Suggests

READ ON

BY BRADLEY W. PARKS / OPB

New research suggests mountain snowpack in the Cascades is among the most vulnerable in the U.S. to the effects of climate change.

Researchers with the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California San Diego say warming will likely hit coastal mountain ranges like the Cascades much harder than their northern inland neighbors.

“What’s happening in the Cascades is even a small amount of warming has this huge impact on the amount of time that the temperature’s really cool enough to have snow on the ground,” climate scientist and lead author Amato Evan said.

Each winter, snow covers our mountains in a thick white blanket. That snow melts as the weather heats up until eventually, at some point during the spring or summer, the mountains are virtually bare — save for the glaciers that clad several peaks in ranges like the Cascades. That day will get earlier and earlier on average as the planet warms.

The researchers hypothesize snow in the Cascades will melt up to a month earlier than it does now with warming of 1 degree Celsius. The same change in temperature would only shift when the snow melts in the Rockies by a day or two.

Evan said that’s because of how temperature varies from place to place.

“If you take a big mountain and you put it next to an ocean, the swings between the wintertime cools and the summertime highs, they’re not super dramatic compared to if we go look at an interior region like in the Rockies,” Evan said.

In other words, if that one degree of warming is a pebble, the Cascades are a still pond. Any disruption to the status quo in the Cascades will be more noticeable.

Mountain snowpack is one indicator of how much water will be available in any given year. The ideal is to have a lot of snow in the winter melt slowly throughout the course of the year. That way, water managers can better predict when and how much water will be available to use for drinking water, irrigation, recreation and more. A stable water supply is also critical for plant and animal life.

Think of mountain snowpack like a bank.

“If you start drawing down that bank prematurely or you’re not putting enough snow in that bank, that hits us,” Evan said. “That depletes our water resources that we have in the Western U.S.”

Smaller and/or faster-melting snowpack can also increase wildfire risk and invite invasive species, Evan added.

“We’re essentially shrinking our winter season and we’re growing that season during which we can have wildfires. And that, to me, is really, really alarming.”

Researchers made their hypotheses using a model based on nearly four decades’ worth of snowpack, temperature and precipitation data at more than 400 sites across the American West.

They theorize snowpack is most vulnerable near the U.S. West Coast, in Central Europe and in South America. In their model, warming affects snowpack less in the northern interior regions of North America, Europe and Asia.

The study was published March 1 in the journal Nature Climate Change.

Oregon’s latest water supply outlook report shows most basins with normal or above-normal snowpack heading into spring. Much of Southern Oregon entered March with a below-normal snowpack. More than 80% of the state was abnormally dry or worse as of March 2, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor.

Copyright 2021 Oregon Public Broadcasting. To see more, visit opb.org

Related Stories:

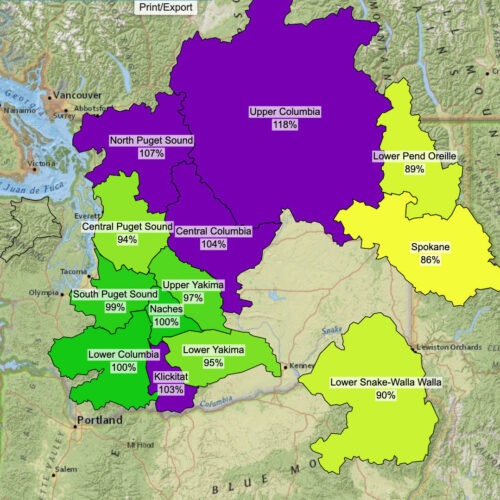

Drought expected to plague farmers in the Yakima Valley, Kittitas areas this summer

Jim Willard shows “bud break” on an old block of concord grapes eight miles north of Prosser, Washington. The baby leaves and buds start pushing out to become grown vines

On The Back-End Of Winter, Washington Snowpack Is Generally Normal, With Idaho A Mixed Bag

With about a month left in winter, Washington’s mountain snowpack is close to or above normal levels. Idaho’s situation is a mixed bag.

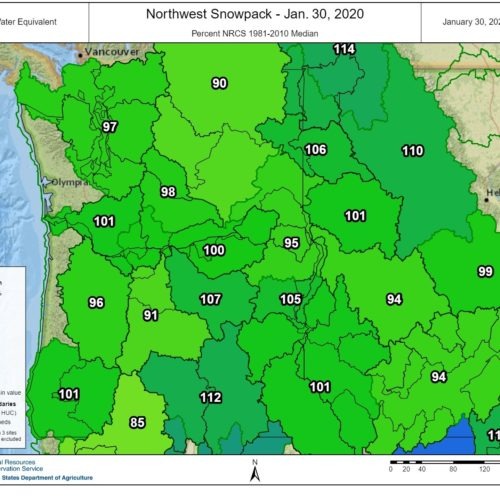

Low Snow To Snowmageddon: January Dumps Gave Needed Bump To Northwest’s Lagging Snowpack

At the start of 2020, the situation looked dismal. After a dry start to the season, Washington and Oregon had less than half the amount of snow they’d normally see in the mountains. Then came the first few weeks of January.