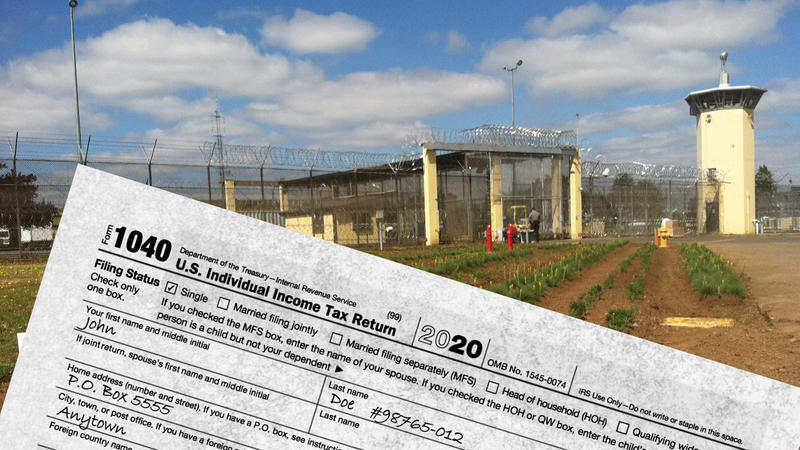

Northwest Prisoners Eligible For Stimulus Checks. But Getting Payout Behind Bars Is Complicated

Listen

Like many Americans, people behind bars are waiting to see if they will be getting checks from the federal government as part of the new stimulus bill — provided it passes Congress this month as expected. The majority of incarcerated people in Washington and Oregon were likely eligible for the first two rounds of relief money.

Advocates for prisoners say the all too common refrain of “What happened to my check?” shows the system for the incarcerated needs to be improved. This comes after a federal judge reversed an initial attempt by the Internal Revenue Service to disqualify inmates from receiving stimulus payments.

Michael J. Moore is serving time at the Monroe Correctional Complex northeast of Seattle for three robberies. He said he was unsure last year whether people like him would get economic stimulus payments.

“There’s this bias against prisoners, you know,” Moore said in a phone interview. “They might say something along the lines of, ‘Why are we giving this money to prisoners? They don’t need it,’ not realizing that some of us do.”

“A lot of prisoners are only incarcerated temporarily,” he continued. “They still have children to support. They have house payments. They have bills and a lot of their families have been affected by Covid to a greater degree with only one breadwinner left in the household, right.”

Moore said he was included in both the $1,200 first round and $600 second round of checks, but none of the money actually reached his pocket.

“I lost all of the money to a child support debt. But fortunately, my child support was paid off after that,” he said with a chagrined laugh.

Moore is the father of two daughters. In prison, a prior interest he had in writing has blossomed into a plethora of published sci-fi/horror novels and nonfiction essays.

Past-due child support is just one of many things that states can deduct from an inmate’s outside income. Other deductions include unpaid court fees and fines, crime victim’s compensation and costs of incarceration — or self-improvement programs, in Oregon’s case.

Catherine Bentley of the Public Defender Association in Seattle is one of a number of legal aid attorneys trying to get more relief money into more prisoners’ hands. On her desk, she said she has a stack of 50 letters from inmates describing heavy garnishment of their federal stimulus checks.

“On average, it’s about 50 to 60 percent,” Bentley said in an interview. “The most egregious was one gentleman who had $900 taken out of his check, which is 75% of the total stimulus money.”

Bentley contended that total deductions over 35% are excessive in most cases, but the Washington State Department of Corrections disagrees. Interim Communications Director Susan Biller said Congress shielded the second round payments from most garnishments, but not the first.

“These are all based on statute. So, we are just processing that based on following the statutes,” Biller said.

Second round economic impact payments were delivered on pre-loaded Visa debit cards to some Americans, including prisoners. CREDIT: Meta Bank

Washington and Oregon’s corrections departments and others found themselves in the middle of a head twisting back and forth that began last spring. It started with Congress directing relief money to go out fast. A short time later, the Internal Revenue Service sent a memo to prisons saying essentially, “Oops, we didn’t mean to cut inmate checks. Send those back.” Months later, a federal judge countered in so many words, “Actually, no, deliver the money after all.”

Second round payments were sometimes sent to prisons on U.S. Treasury debit cards, which are useless behind bars. Corrections departments mostly sent those back to the IRS. Washington’s prison system said it held on to debit cards addressed to inmates with release dates in the next three months so they might have a leg up on reentry.

For its part, the IRS raised questions last year about whether prisoners should receive relief money. When that came before a federal court in Northern California, the IRS argued Congress didn’t clearly include prisoners and that withholding their checks would help protect against possible fraud.

“The threat of COVID-19 has presented unique dangers for incarcerated individuals,” wrote U.S. Justice Department Trial Attorney Landon Yost in a September court filing. “However, as a general matter, prisoners are also more insulated from the economic effects of the pandemic than many others because their basic needs such as food, shelter, and health care are already being provided for by the state and paid for by taxpayers.”

But Bentley said the court made it clear in the class-action lawsuit brought by aggrieved prisoners that incarcerated people are entitled to the federal relief money “just like everyone else is.”

Washington’s Department of Corrections said just shy of 3,000 inmates out of a total population in custody of nearly 15,000 got first round checks deposited into their prison accounts. The Oregon Department of Corrections said it received and deposited slightly fewer than 500 first round checks on behalf of prisoners out of a total population in custody of more than 12,000. The second round of payouts went a little better in Oregon with the DOC reporting it processed nearly 1,700 deposits totalling more than $1 million.

To Alice Lundell, director of communication for the Oregon Justice Resource Center in Portland, it seemed “somewhat random as to who has got it and who hasn’t.”

A difficult-to-ascertain number of prisoners had their stimulus payment deposited in a joint account on the outside managed by a spouse or relative. Those fortunate to maintain such family connections had better luck collecting what they qualified for.

Advocacy groups are highly critical of what they consider to be roadblocks created by state prison policies, which they said made it difficult for folks to claim money that was theirs.

“There was willful negligence,” claimed Rory Elliott, an organizer with Critical Resistance PDX, who cited instances reported to her group where guards allegedly failed to hand out all of the instructions inmates needed to file for stimulus payments.

Filing a tax return is the best way for most Americans to make sure they’re on the government’s radar for a check. Easier said than done though from behind bars.

Oregon Department of Corrections Communications Manager Jennifer Black said her agency shared eight separate memos since May 2020 with inmates to provide information about stimulus payments and answers to frequently asked questions.

Biller said the Washington DOC has tried to assist by distributing model tax forms. Generally, it takes its cues on this issue from the federal government.

“I believe that we will do as instructed,” Biller said in an interview this week. “It is always helpful when they provide us with clear information that stays the same moving forward.”

Legal aid groups in Oregon and Washington state said they are now laying the groundwork for a mass mailing of tax forms and instructions once Congress finalizes round three of the pandemic payments.

Related Stories:

Federal funding cuts, freezes hit Palouse nonprofits

Palouse area nonprofits focused on helping with emergency food and the arts have had their funding frozen or cut.

Why affordable housing providers say they’re facing an ‘existential’ crisis

Affordable housing providers across the Northwest have been contending with rising insurance premiums — and, in some cases, getting kicked off their plans altogether.

Pacific Northwest author’s new novel captures atmosphere of the region

On a gray, early spring morning, I drove to Steilacoom, Washington, to catch the ferry to Anderson Island. I boarded alongside the line of other cars and after parking, stepped out onto the deck of the boat. The ferry pushed off from the dock and rocked a little in the Puget Sound before steadying.

I took this journey to the real Anderson Island to see from the water what inspired Northwest author Kirsten Sundberg Lunstrum’s new novel, “Elita,” which was published earlier this year. Sundberg Lunstrum was inspired while sailing around the Puget Sound to write a mystery novel on an island.

Sundberg Lunstrum read excerpts of the book at a gathering at Tacoma’s Grit City Books.