Why We Can’t Make Vaccine Doses Any Faster

BY ISAAC ARNSDORF & RYAN GABRIELSON / ProPublica

Originally published Feb. 19, 2021 by ProPublica, a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative newsroom. Sign up for The Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox.

President Joe Biden has ordered enough vaccines to immunize every American against COVID-19, and his administration says it’s using the full force of the federal government to get the doses by July. There’s a reason he can’t promise them sooner.

Vaccine supply chains are extremely specialized and sensitive, relying on expensive machinery, highly trained staff and finicky ingredients. Manufacturers have run into intermittent shortages of key materials, according to the U.S. Government Accountability Office; the combination of surging demand and workforce disruptions from the pandemic has caused delays of four to 12 weeks for items that used to ship within a week, much like what happened when consumers were sent scrambling for household staples like flour, chicken wings and toilet paper.

People often question why the administration can’t use the mighty Defense Production Act — which empowers the government to demand critical supplies before anyone else — to turbocharge production. But that law has its limits. Each time a manufacturer adds new equipment or a new raw materials supplier, they are required to run extensive tests to ensure the hardware or ingredients consistently work as intended, then submit data to the Food and Drug Administration. Adding capacity “doesn’t happen in a blink of an eye,” said Jennifer Pancorbo, director of industry programs and research at North Carolina State University’s Biomanufacturing Training and Education Center. “It takes a good chunk of weeks.”

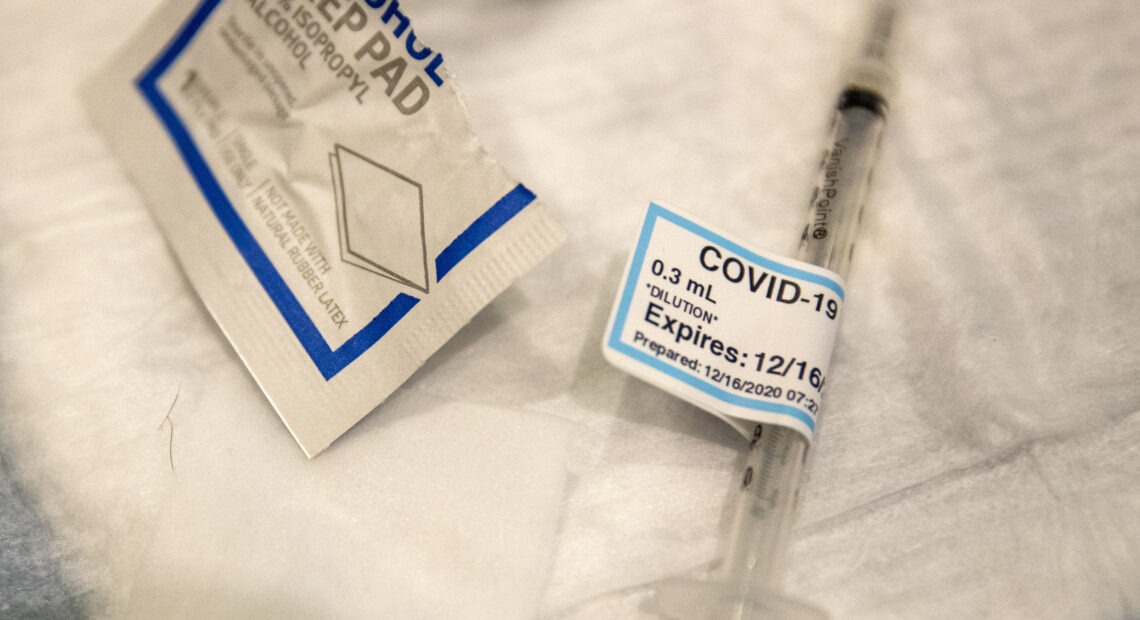

An empty syringe on a table at Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center after a care worker received the COVID-19 vaccine on Dec. 16, 2020. CREDIT: Brian van der Brug/AP

And adding supplies at any one point only helps if production can be expanded up and down the entire chain. “Thousands of components may be needed,” said Gerald W. Parker, director of the Pandemic and Biosecurity Policy Program at Texas A&M University’s Scowcroft Institute for International Affairs and a former senior official in the Department of Health and Human Services office for preparedness and response. “You can’t just turn on the Defense Production Act and make it happen.”

The U.S. doesn’t have spare facilities waiting around to manufacture vaccines, or other kinds of factories that could be converted the way General Motors began producing ventilators last year. The GAO said the Army Corps of Engineers is helping to expand existing vaccine facilities, but it can’t be done overnight.

Building new capacity would take two to three months, at which point the new production lines would still face weeks of testing to ensure they were able to make the vaccine doses correctly before the companies could start delivering more shots.

“It’s not like making shoes,” Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said in an interview with ProPublica. “And the reason I use that somewhat tongue-in-cheek analogy is that people say, ‘Ah, you know what we should do? We should get the DPA to build another factory in a week and start making mRNA.’ Well, by the time a new factory can get geared up to make the mRNA vaccine exactly according to the very, very strict guidelines and requirements of the FDA … we already will have in our hands the 600 million doses between Moderna and Pfizer that we contracted for. It would almost be too late.”

Fauci added that the DPA works best for “facilitating something rather than building something from scratch.”

The Trump administration deployed the Defense Production Act last year to give vaccine manufacturers priority in accessing crucial production supplies before anyone else could buy them. And the Biden administration used it to help Pfizer obtain specialized needles that can squeeze a sixth dose from the company’s vials, as well as for two critical manufacturing components: filling pumps and tangential flow filtration units. The pumps help supply the lipid nanoparticles that hold and protect the mRNA — the vaccines’ active ingredient, so to speak — and also fill vials with finished vaccine. The filtration units remove unneeded solutions and other materials used in the manufacturing process.

These highly precise pieces of equipment are not typically available on demand, said Matthew Johnson, senior director of product management at Duke University’s Human Vaccine Institute, who works on developing mRNA vaccines, but not for COVID-19. “Right now, there is so much growth in biopharmaceuticals, plus the pinch of the pandemic,” he said. “Many equipment suppliers are sold out of production, and even products scheduled to be made, in some cases, sold out for a year or so looking forward.”

In the meantime, the shortage of vaccines is creating widespread frustration and anxiety as eligible people struggle to get appointments and millions of others wonder how long it will be before it is their turn. As of Feb. 17, the U.S. had distributed 72.4 million doses and administered 56.3 million shots, but fewer than 16 million people have received both of the two doses that the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines require for full protection.

The Biden administration has said it is increasing vaccine shipments to states by 20%, to 13.5 million doses a week, and encouraged states to give out all their shots instead of holding on to some for second doses. But now that second-dose appointments are coming due, many jurisdictions are having to focus on those and stepping back from vaccinating uninoculated people. Even as the total number of vaccinations increased last week, the number of first doses fell to 6.8 million people, down from 7.8 million three weeks ago, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data.

At best, it will take until June for manufacturers to deliver enough doses for the roughly 266 million eligible Americans age 16 and over, according to public statements by the companies.

In December 2020, federal regulators granted an emergency use authorization to the vaccine developed by Moderna, whose Cambridge, Mass., headquarters are seen here. CREDIT: Elise Amendola/AP

That includes expected deliveries of Johnson & Johnson’s one-dose vaccine, which is widely expected to win emergency authorization from the FDA shortly after a public advisory committee meeting on Feb. 26. But Johnson & Johnson has fallen behind in manufacturing. The company told the GAO it will have only 2 million doses ready to go by the time the vaccine is authorized, whereas its $1 billion contract with HHS scheduled 12 million doses by the end of February. It’s not clear what held up Johnson & Johnson’s production line; the company has benefited from first-priority purchases thanks to the DPA, according to a senior executive close to the manufacturing process. A Johnson & Johnson spokesman declined to comment on the cause of the delay, but said the company still expects to ship 100 million U.S. doses by July.

Moderna declined to comment on “operational aspects” of its manufacturing, but “does remain confident in our ability to meet contracted quantities” of its vaccine to the U.S. and other nations, a spokesperson said in a statement. Pfizer did not respond to ProPublica’s written questions.

Ramping up production is especially challenging for Pfizer and Moderna, whose vaccines use an mRNA technology that’s never been mass-produced before. The companies started production even before they finished trials to see if the vaccines worked, another historic first. But it wasn’t as if they could instantly crank out millions of vaccines full blast, since they effectively had to invent a novel manufacturing process.

“Putting together plans 12 months ago for a Phase 1 and 2 trial, and making enough to dose a couple hundred patients, was a big deal for the raw material suppliers,” said Johnson, the product manager at Duke University’s vaccine institute. “It’s just going from dosing hundreds of patients a year ago to a billion.”

Raw materials for the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines are also in limited supply. The manufacturing process begins by using common gut bacteria cells to grow something called “plasmids” — standalone snippets of DNA — that contain instructions to make the vaccine’s genetic material, said Pancorbo, the North Carolina State University biomanufacturing expert.

Next, specific enzymes cultivated from bacteria are added to cause a chemical reaction that assembles the strands of mRNA, Pancorbo said. Those strands are then packaged in lipid nanoparticles, microscopic bubbles of fat made using petroleum or plant oils. The fat bubbles protect the genetic material inside the human body and help deliver it to the cells.

Only a few firms specialize in making these ingredients, which have previously been sold by the kilogram, Pancorbo said. But they’re now needed by the metric ton — a thousandfold increase. Moderna and Pfizer need bulk, but also the highest possible quality.

“There are a number of organizations that make these enzymes and these nucleotides and lipids, but they might not make it in a grade that is satisfactory for human consumption,” Pancorbo said. “It might be a grade that is satisfactory for animal consumption or research. But for injection into a human? That’s a different thing.”

Johnson & Johnson’s vaccine follows a slightly more traditional method of growing cells in large tanks called bioreactors. This takes time, and the slightest contamination can spoil a whole batch. Since the process deals with living things, it can be more like growing plants than making shoes. “Maximizing yield is as much of an art as it is a science, as the manufacturing process itself is dependent on biological processes,” said Parker, the former HHS official.

The vaccine developers are continuing to find tweaks that can expedite production without cutting corners. Pfizer is now delivering six doses in each vial instead of five, and Moderna has asked for permission to fill each of its bottles with 15 doses, up from 10. If regulators approve, it would take two or three months to change over production, Moderna spokesman Ray Jordan said on Feb. 13.

“It helps speed up and lighten the logistical side of getting vaccines out,” said Lawrence Ganti, president of SiO2, an Alabama company that makes glass vials for the Moderna vaccine. SiO2 expanded production with $143 million in funding from the federal government last year, and Ganti said there aren’t any hiccups at his end of the line.

Despite the possibility of sporadic bottlenecks and delays in the coming months, companies appear to have lined up their supply chains to the point that they’re comfortable with their ability to meet current production targets.

Massachusetts-based Snapdragon Chemistry received almost $700,000 from HHS’ Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority to develop a new way of producing ribonucleoside triphosphates (NTPs), a key raw material for mRNA vaccines. Snapdragon’s technology uses a continuous production line, rather than the traditional process of making batches in big vats, so it’s easier to scale up by simply keeping production running for a longer time.

Suppliers have told Snapdragon that they have their raw materials covered for now, according to Matthew Bio, the company’s president and CEO. “They’re saying, ‘We have established suppliers to meet the demand we have for this year,’” Bio said.