Past As Prologue: End Times Preaching In Seattle And The Politics Of The Apocalypse

Listen

NOTE: The following essay and its audio component are part of an ongoing series produced in conjunction with the Washington State University history department. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the author.

BY MATTHEW SUTTON

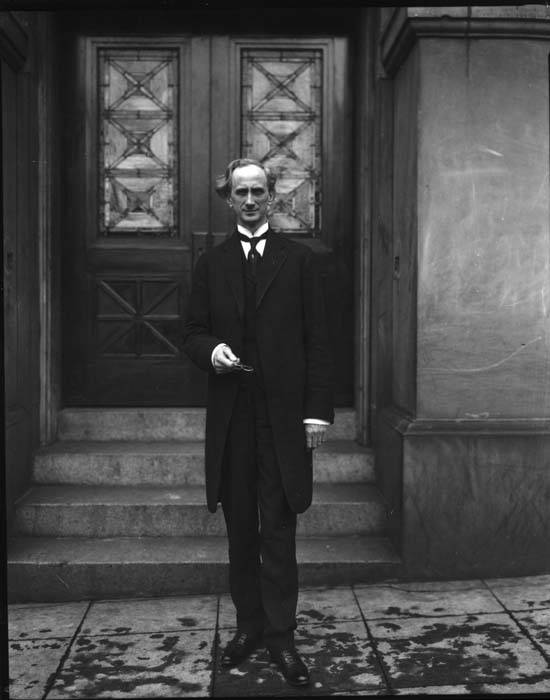

Seattle minister Mark Matthews loved God. And he loved Woodrow Wilson. The tall, lanky, Georgia-born preacher, who looked more like a stern plantation overseer than a warm cleric, relished the fact that Presbyterian and Democrat Woodrow Wilson was in the White House.

WSU History Professor Matthew Sutton, Berry Family Distinguished Professor in the Liberal Arts Department Chair. CREDIT: WSU/Matthew Sutton

During the early decades of the 20th century, Matthews became one of the most powerful religious leaders in the United States. His Seattle congregation was the largest Presbyterian church in the world with more than 10,000 members at its peak.

Early in his career, Matthews was an optimist, believing in the power of the Christian gospel to establish a literal kingdom of God on Earth. But by the mid-1910s, he determined that the world was careening towards the biblical end times. Like many radical evangelicals of his generation witnessing European nations armed for war, Matthews preached the end was nigh. Jesus, he predicted, was coming back to fight Satan at the battle of Armageddon. And soon.

But this didn’t make Matthews indifferent to worldly affairs. He routinely wrote President Wilson with advice and to ask for favors for himself and his friends. He even promised to get congressional pork flowing back to the Pacific Northwest. The president occasionally sought Matthews’ opinions in return. Despite Matthews’ apocalyptic world views, he had the ear of the president and no reservations about speaking boldly to men in power.

Matthews was not alone in preaching the end times. Christian apocalypticism has a long and varied history. The modern incarnation of Christian apocalypticism took shape about a century ago. Baptists, Methodists, Presbyterians, Pentecostals and independents shared a commitment to returning the Christian faith to its “fundamentals.” They masterfully use the Bible’s most cryptic passages to explain the past, understand the present, and predict the future.

Matthews’ work highlights the paradox that lie at the heart of fundamentalists’ work. They believed in two almost paradoxical principles. First, fundamentalists felt certain that the battle of Armageddon and Second Coming of Christ was imminent. Second, they believed Jesus has nevertheless called them to “occupy” this world until that imminent return. These convictions worked in concert to inspire in fundamentalists bold, relentless, unapologetic, and aggressive action unparalleled in modern Christendom.

With time running out, fundamentalists and evangelicals intended to shake the world. They sought instant redemption, immediate transformation. Hence Billy Sunday preached Prohibition and Jerry Falwell extolled the virtues of limited government and Billy Graham harangued against gay rights while each simultaneously believed that the end was near. They were preparing the world for the final judgment, hoping to redeem as many people as possible before all was lost. Theirs was a politics of apocalypse.

As evangelicals’ power and influence has grown in the 21st century, they are investing more in this world than in preparing for the next. Yet a recent poll revealed that 41% of all Americans (well over one-hundred million people) and 58% of white evangelicals believe that Jesus is “definitely” or “probably” going to return by 2050. Even here in the Pacific Northwest, where church membership has been declining for decades, end-times preaching attracts hundreds of thousands of adherents.

The conviction that the end is near is all the incentive evangelicals need to continue to spread their faith—with all of its social and political ramifications—as aggressively and widely as possible. Evangelicalism, perhaps better than competing faiths, provides millions of people navigating a chaotic and seemingly meaningless world with purpose, significance and incentive for action. That was Mark Matthews’ genius, and that is the genius of modern evangelicalism.

Related Stories:

Past As Prologue: Gendered Epithets In Pacific Northwest Politics And Beyond

Past as Prologue essay about gendered epithets in Pacific Northwest politics and beyond.

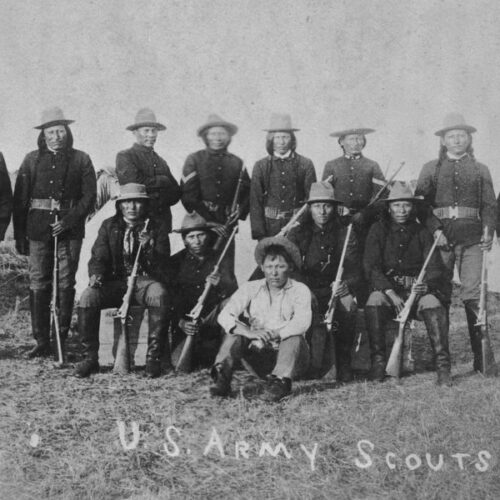

Past As Prologue: The Complicated Relationship Between Indian Scouts And The U.S. Government

The story of some Native American Scouts and their complicated reasons for working with the United States government.

Past As Prologue: The Non-Coastal Inland Northwest’s Big Ties To The Ocean Shipping Industry

In this Past as Prologue essay, WSU Professor Karen Phoenix explains the history of the shipping container and its Spokane ties.