Author Leah Johnson On Being Young, Black, Queer And In Love

BY SUMMER THOMAD

This week on Code Switch, we’ve been talking about the joys and complexities of Black romance. On the podcast, we delved in historical Black romance with authors who write about Black love during slavery, Reconstruction, the roaring ’20s, the civil rights movement. But with Valentine’s Day upon us, we didn’t want to leave out Black romance that takes place in the here and now.

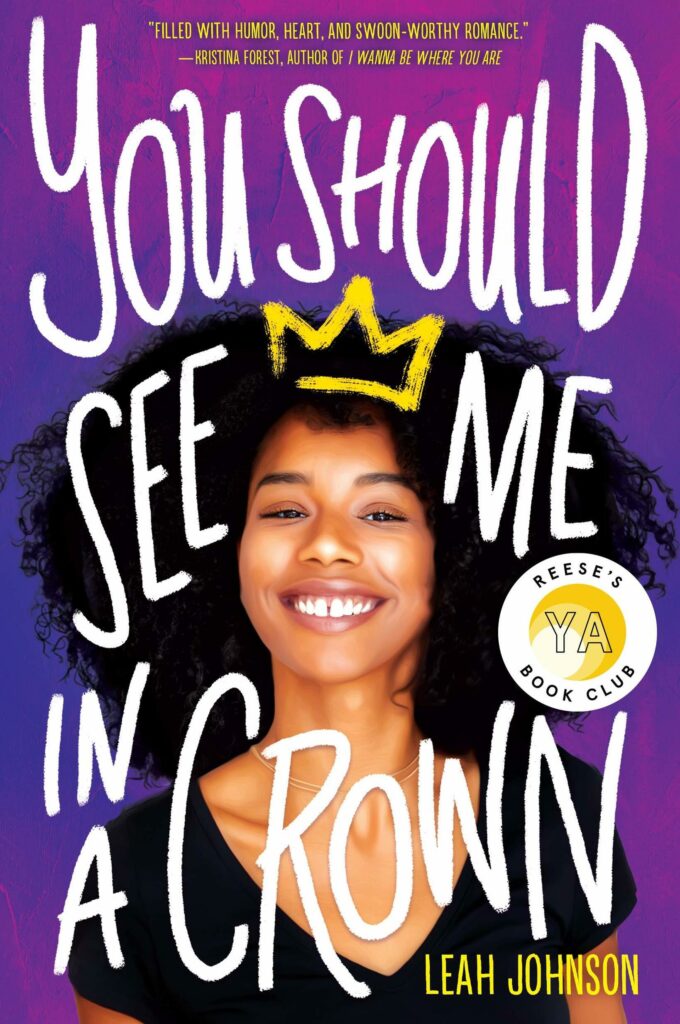

So we called up Leah Johnson, author of You Should See Me In A Crown. The young adult novel follows Liz Lighty, a high schooler who has always felt “too Black, too poor, and too awkward” for her rich, mostly white, midwestern town. When Liz’s financial aid falls through, she decides her only option is to run for prom queen in order to win the scholarship she needs to afford her dream college. Romantic antics ensue. The book dives into the struggles of growing up Black and queer in a place where that’s not the norm, but manages to still celebrate all kinds of love: platonic, familial and romantic.

Author Leah Johnson.

Courtesy of Leah Johnson

Johnson says she wrote You Should See Me in a Crown for her readers, yes, but also for herself: “I wanted to remind myself that it is possible to be Black and queer and from where you’re from, and still get all the best things out of life.”

This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

For people who haven’t read You Should See Me In A Crown, what is it about?

You Should See Me In A Crown is about a girl named Liz Lighty, whose only goal is to get out of her small and small minded Midwestern home town and go to college. But those plans are derailed when her financial aid falls through and she has to run for prom queen for the scholarship that’s attached to the crown. That would be difficult enough for a wallflower like Liz, but it’s made even more difficult when she begins to fall for her competition.

How did you get into writing young adult fiction, and specifically YA stories that center Black and queer heroines?

When I was younger, we didn’t get stories where Black queer girls in particular got happy endings, where they got swoon-worthy romances, where they got to be crowned queens and told that they were worthy. All the books that I loved most growing up were white girls getting those stories. And I realized they would throw a white girl into eight million different, impossible situations where she would fall in love, and a Black girl couldn’t get even the most basic happy ending love story.

“You Should See Me In A Crown” by Leah Johnson

I wanted to write a book that was very much an homage to the work that I love the most, which were the John Hughes movies of the eighties, the teen romantic comedies of the late ’90s, early aughts – we’re talking A Cinderella Story, Drive Me Crazy, 10 Things I Hate About You. I love those stories so much and wanted to see someone like me reflected in them as more than a sidekick.

Who is the primary audience that you hold in your mind while you’re writing?

[The playwright and poet] Ntozake Shange has this quote that I really love: “I write for all the young girls of color who don’t even exist yet so that there’s something there for them when they arrive.” I think about 15-year-old me, who was scared of everything but wanted so badly for someone to love her and to be seen as a whole person for all the parts of who I am. I write for my nieces, who are 14 and 18. I write for all the girls in this town, who nobody pays attention to but deserve all of the praise and credit and all the happiest endings. There are so many young, queer Black people that deserve so much better than what we’ve gotten, both on the page and in the world.

We see a lot of narratives that hold up the image of Black trauma. Black joy is only granted in exchange for Black suffering. So what’s really important to me is to give my characters love that doesn’t have to be earned. They are given love simply because they are human beings who deserve it. I think if I had more images of that growing up, and to be honest, if I got more images of it right now, I think the way that I approach my own desire, and the way that I approach my romantic relationships would have been much different early on.

What do you have to think about writing a queer Black romance for young readers that you wouldn’t if you were writing for adults?

Most of the things I consider in this book are things that I would consider at any stage: how my community is going to respond to my coming out, or how that’s going to influence the ease with which I get to move through a space, whether it’s at a school or a workplace or the way people receive me when I’m wearing a pride flag at Starbucks.

That said, Liz is reckoning with all those things on top of the massive responsibility of making decisions about who you want to be, and what you want from your life at 17 or 18 years old. She also has to worry about, “Is somebody going to make fun of me if I change the way I wear my hair?” I don’t care about that as an adult, but for someone in high school, how your classmates perceive you is the primary concern. So talking about college, talking about money, the way a teenager metabolizes poverty, is going to be way different than that of an adult. It’s a lot of feeling powerless, but also feeling like you’re supposed to have all the power in the world because you’re young.

I was struck by how real so many of Liz’s relationships felt, from her relationship with her family, to her friendships, to her romantic interest. Why was it important to portray the complexities of all these different types of relationships in a book about romance?

The things that taught me the most about love were not romantic relationships. They were my group chats, which taught me how to be better communicators. They were my friends, my mutuals on Twitter, who taught me how to be more honest without being hurtful. They were my family, who told me and taught me how to love unabashedly, but also how to apologize when I have done something wrong. These are tools that, of course, are really helpful in a romantic relationship and can inform the way that you approach romance.

But to me, the most important relationships in my life have always been the people I love platonically. And so it’s important for me to show that it is possible to have strong platonic relationships, but also that those relationships can be equally as important, if not more important, than the romance itself. I love kissing scenes, I love the scene in the book where they held hands at the concert. Those moments warm my heart. But the thing that really energizes me is being able to write about all these people who remind me so much of the people in my own life who taught me how to wear my crown.

While You Should See Me In A Crown ultimately has a happy ending, Liz’s conflict throughout the book is rooted in racism, classism and homophobia present in her community. How did you strike a balance between telling a story that addressed all the -isms while also creating space for joy?

A friend of mine, Adiba Jaigirdar, who’s the author of the book The Henna Wars, said once that she doesn’t wake up in the morning and decide which day is going to be her “hate crime day,” which day is going to be her “women’s empowerment day” which day is the “meet-cute day.” All these things happen at once for marginalized people, and specifically queer people of color. The best way for me to think about any story about a young queer Black girl falling in love is that I hold great pain and great joy in my hands at the same time, at all times. Any story about what it’s like for me to fall in love is going to be something that reckons with the world that I have to move through in order to fall in love.

If I was going to tell a story in which Liz does have to deal with microaggressions and some macroaggressions in her small town, then I was also going to give her joy that outweighed whatever sadness she faced tenfold. I wanted it to be so clear that, yeah, this is a real thing that happens to people like me. But past that, I also have a life that is so rich and filled with so much love and so much care from these people who raised me and from my friends who go to great lengths to support me. That those things are terrible, but also, I still have a life that is worth living and celebrating and honoring.