How To Watch, What To Know: Your Guide To The Impeachment Trial Of Donald Trump

IMPEACHMENT TRIAL: Watch Live Here

BY LISA DESJARDINS / PBS NewsHour

We have a special place in history. Never have Americans been so experienced in presidential impeachment as we. Two impeachments in just more than a single year.

Nonetheless, experience does not yield understanding. Impeachment is a rare and confusing process. This is just the fourth presidential impeachment in history. And each impeachment process and set of arguments is slightly or dramatically different from the last.

With that in mind, we asked for your questions about impeachment. And happily you sent us boatloads. Thank you. Let’s tackle them.

Who decides how impeachment trials work?

Brilliant first question! (If planted.) This is key to understanding impeachment. Each Congress has the power to set up its own impeachment process.

Similarly, each Senate defines the criteria for conviction of “high crimes and misdemeanors.” Precedent plays a role, but it can be easily crushed by the will of the Senate at any time. Witnesses? Allowed (via video) in 1999, not in 2020. Committee hearings first? Sure, in 1973, 1999 and 2020. But nope, not in 1868 or in 2021.

IMPEACHMENT TRIAL: Watch Live Here

Essentially, the way the founders laid it out in the Constitution, impeachment is whatever and works however each Senate wants. The Supreme Court ruled in a unanimous 1993 decision, U.S. v. Nixon, that impeachment is “nonjusticiable.” That means it cannot be handled or defined by judges but instead must be crafted and sculpted by Congress itself. Unique in our system, Congress here is law and court both.

One of the only criteria set in stone is constitutional. It takes a two-thirds Senate vote to convict.

From @LisaDNews. Related question from @ballsimpsons

In what order does the whole process take place?

Perfect question. Now to the roadmap.

Think of this impeachment trial in the Senate as having six phases, in this order.

- Can the Senate hold this trial? Each side argues whether Congress can impeach and try a former U.S. president. When? Today.

- General arguments. Each side has up to 16 hours to present their overall case. Starts Wednesday, over by the end of Sunday.

- Senators’ questions. They get four hours total.

- Witnesses?If either side requests, the Senate will consider calling witnesses. But they must first debate that idea and then a majority must approve it.

- Closing arguments. Two hours for each side.

- Possible deliberation and final vote by senators.

From @Maggieosceola

Likelihood of witnesses?

More process! And succinct. I will reply in turn. The likelihood of witnesses is so slim it is almost invisible.

All sides are highly motivated to have a fast trial. Democrats, to move on the Biden agenda. Republicans, to just move on. In addition, some senators consider themselves to be witnesses in this particular trial.

From @eroseSCS

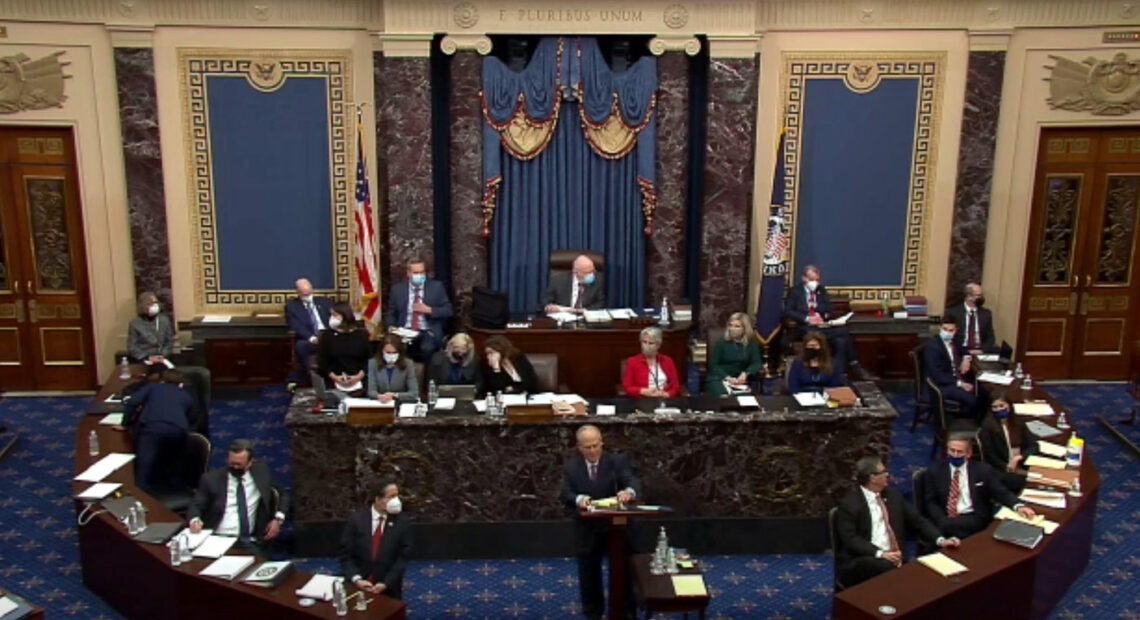

The Senate voted Tuesday that the trial of former President Donald Trump is constitutional and that he can be subject to the Senate as a court of impeachment.

CREDIT: Handout/Getty Images

Can the “prosecution” call people who broke into the Capitol to testify?

As with much about the U.S. Senate, the answer is yes, if the Senate allows it.

House managers, who are prosecuting the case here, can request to call witnesses. But, as above, the Senate then must approve that idea. Complicating matters in your question, those who broke into the Capitol could use their Fifth Amendment rights and refuse to give testimony that could self-incriminate.

Regardless, we do expect House managers to show these individuals virtually, by playing some social media clips and other videos from the day of the riot.

@IVMEJANE

IMPEACHMENT TRIAL: Watch Live Here

What are the rules of secret ballots on the Senate floor to allow officials to vote their conscience without fear of reprisal in these highly emotional times?

Wow this was a popular question. And a good one.

Can the Senate hold a secret ballot vote on Trump’s impeachment? Yes, but only if more than 80 percent of the Senate wants it to happen.

This is not flexible. It’s in the Constitution, not in the slightly more elastic volume of Senate rules.

Article I, Section 5 states, “the Yeas and Nays … on any question shall, at the Desire of one fifth of those Present, be entered on the Journal.”

Thus, if one-fifth, or 20 members, of the U.S. Senate want a public vote, they will get it. Additionally, it is the default position that the impeachment vote will be public.

From @Squirrel_BD

Now to a related question.

Will all senators state their votes and the reasons that they cast them on the record?

Yes, each senator is expected to stand and announce their vote, by saying “aye,” “nay” or “present.” No, senators are not required to give their reasoning.

Some may do that, but there is relatively little time for remarks or speeches by senators in this trial. The most likely insight into why senators vote will come in either their own press releases or conversations with reporters afterward.

From @JoJostekes

I have a copy of the draft articles of impeachment, but is there a link to the final text?

Sure thing. The Article of Impeachment, as passed by the House of Representatives, is House Resolution 24. You can read it here.

From @az_michelle_w

What would a conviction mean? Could Trump be jailed, or would it just end his ability to run for office again?

If the Senate convicts Mr. Trump, it would then face another decision: how to penalize him. The most likely direction would be to ban Trump from running for federal office again, since removing him from office is off the table. That would be a separate vote, requiring only a majority of Senators, not two-thirds.

From @embedee

If the senate convicts & bars him from future office, could Trump contest the constitutionality in court?

Yes, he absolutely could attempt an appeal.

But, that is uncharted territory and past court rulings do not indicate a high likelihood of success. Most federal courts have punted on cases dealing with power battles between the first and second branches of government. They often revert back to initial rulings or the status quo.

Moreover, there is that 1993 U.S. v. Nixon case that set the precedent that impeachment exists outside the federal court system.

From @heyalexio

Related: Can senators, like Hawley also be impeached (in a separate impeachment vote/trial)?

You’ve opened a fascinating question.

The Constitution, in Article I, Section 5, gives each chamber the power to “punish its members for disorderly behavior, and, with the concurrence of two-thirds, expel a member.” At this point, 1994 individuals have served in the U.S. Senate. Of those, just 15 have been expelled and 14 of those were expelled for supporting the Confederacy during the Civil War.

In other words, Senate expulsion is possible, but incredibly rare.

Senate impeachment, meaning an impeachment trial for a senator, is rarer still, having occurred only once, with Sen. William Blount of Tennessee in 1797. But the Blount trial left an open question as to whether impeachment of a Senator is possible.

Blount was expelled for attempting to help the British take over part of Florida, in a scheme where he stood to profit. After he was expelled, Congress additionally held an impeachment trial. The Senate voted that it did have the power to impeach him, but it remains unclear if senators believed that was because he had been a senator or if it was because he had already been expelled.

We spent a minute on this here because Mr. Blount is certain to come up in this impeachment trial more than 200 years later.

From @NaglTt

Do you have a whip count?

I have a nerdy spreadsheet but it’s far from a formal whip count (a tally of how each senator is likely or committed to vote). For that I highly recommend this one by the Washington Post.

From @claycompton

Please explain the Constitutional connection and why the GOP questions the validity.

The issue here is that the Constitution does not clearly state whether a former official can be impeached after leaving office. Each side of the debate sees implications one way or the other, but it is not clearly spelled out.

Those who say impeachment is not possible for ex-officials point to this clause. “The President, Vice President and all civil officers of the United States, shall be removed from Office on Impeachment for, and Conviction of, Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.”

They stress “shall be removed” indicates the person must be in office.

But not so fast, say their opponents, who argue that the clause simply spells out why a person should be removed — not that it limits the impeachment power.

They point to this clause, also in Article 1, that says “Judgment in Cases of Impeachment shall not extend further than to removal from Office, and disqualification to hold and enjoy any Office of honor …” The concept here is that the Constitution provides explicitly for the ability to bar someone from holding future office and that, this logic goes, applies to current and former office holders.

From @drcovel.

What is the answer? Again, it is whatever the Senate at the time says it is. By simple majority vote.

Was there ever a case, when the Founding Fathers were alive, and after the constitution was written and signed, that they were faced with the impeachment of a government official after they had left office?

Not exactly. But there are two important cases that are similar and will come up a lot.

- Warren Hastings. An 18th-century Brit who could go semi-viral at the trial.

As the founders were writing the Constitution, the British parliament was holding an impeachment of a former governor of India, a man named Warren Hastings. James Madison noted that fellow founder George Mason brought this up as they created the American version of impeachment. Democrats will argue this shows that the founders absolutely understood and endorsed the idea of impeaching former officials.

- William Belknap. A 19th-century American who is suddenly very important.

During the tumultuous year of 1876, an unhappy Congress moved to impeach President Ulysses S. Grant’s secretary of war, William Belknap.

Belknap resigned first. But the Senate moved ahead with the trial nonetheless, actually voting that it had the power to do so despite the fact that Belknap was no longer in office. Democrats argue this is a clear and strong precedent. President Trump’s team does not dispute that vote, but argues that the outcome — a vote NOT to convict — indicates that the Senate was unsure about its power in the case.

Are senators required to be physically present for all the proceedings, or can they just choose to not show up on the day (for instance) that the impeachment managers decide to show the videos?

Senators are required by the rules to be present and at their desks. However, because of the coronavirus pandemic, the Senate is making some adjustments to this. Senators will be allowed to sit in the balconies of the chamber as well as in an adjoining room where there will be television monitors

From @DMalehorn

What would a conviction mean? Could Trump be jailed, or would it just end his ability to run for office again?

Impeachment is a political process, meaning it affects a person’s status politically: whether they stay in office or can hold future office. It does not have any direct impact on whether an individual faces criminal repercussions, like jail time.

That is a separate prosecutorial process.

Thus, Trump could lose his ability to hold future federal office if convicted in impeachment, but that is the extent of possible punishment.

@embedee

So we all know what happens if he gets 67 votes or more, but what if he gets between 50 and 66, does that mean anything?

In this case, the president is acquitted.

But the final number may have short-term meaning politically.

Democrats will certainly highlight how many Republicans vote to convict, especially if it is greater than the single conviction vote, by Sen. Mitt Romney, R-Utah, in 2020.

From @JonathanShogun

Copyright 2021 PBS NewsHour. To see more, visit pbs.org/newshour