Sifting Through ‘Unsettled Ground’ Of The Whitman Massacre To Reckon With Northwest History

BY KNUTE BERGER / CROSSCUT

The word “reckoning” has resounded throughout the country over the past year. It is a toting up of bills due, a settling of accounts. It is difficult to reckon without facts and figures. When it comes to race, history, cultural trauma and violence, a “reckoning” can ring out as a guilt-inducing charge with no real instruction on how to make things right, or how to proceed at all.

One way to inch forward is to learn the truth, to take in stories and take stock of deeds and transmute that learning into understanding. This is something history can help with. We have seen it in the movement to remove or reconsider Confederate statues, for example, to learn the context of why they were sculpted and erected, and the white supremacist message they were intended to convey. That discussion is now broader, too: Why have we memorialized enslavers, Indian killers and other promoters of white supremacy? Where did these monuments come from, and what is their full story? To deal with a legacy, you need to know about it.

A timely recent book, Unsettled Ground: The Whitman Massacre and Its Shifting Legacy in the American West, steps into this regional discussion. It is by Cassandra Tate, a longtime contributor to HistoryLink.org, and was published in November by Sasquatch Books. The book is a balanced and deeply researched history of Marcus and Narcissa Whitman, key figures in the settling of the Oregon Territory, which once included Washington, Oregon, Idaho, western Montana and a slice of Wyoming.

In “Unsettled Ground: The Whitman Massacre and Its Shifting Legacy in the American West,” author Cassandra Tate examines the death of Washington missionaries Marcus Whitman and his wife Narcissa, along with eleven others, on November 30, 1847, near Walla Walla, Washington. CREDIT: Sasquatch Books

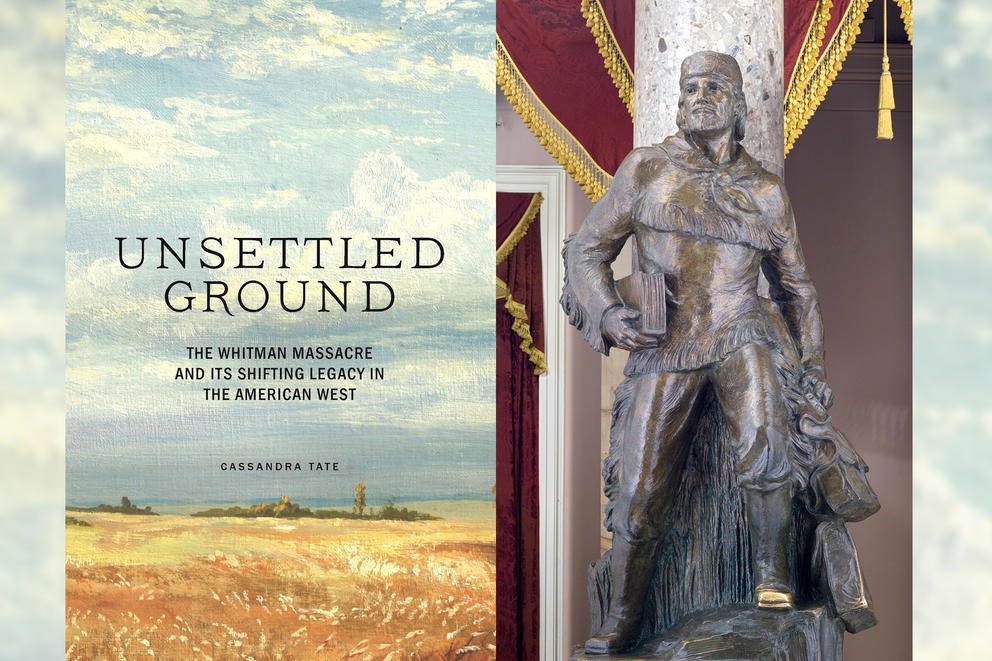

The Whitmans came here as missionaries to convert the Indigenous occupants of the land, whom they considered “heathens,” to their version of Calvinist Christian faith. They settled near present-day Walla Walla. A county and prestigious college in Washington is named for them, and statues of Marcus Whitman stand in Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol, and in the state Capitol in Olympia. The Whitmans were eventually killed by members of the Cayuse tribe — the “massacre” of Tate’s title — alongside a number of other whites were also attacked and killed. That event has reverberated since and has become a kind of cause célèbre among early American pioneers. (“Massacred” was the common term at the time, though, as Tate points out, when American Indians killed whites it was called a “massacre”; when whites killed Indigenous people, it often gets labeled a “battle.”)

In recent years, tributes to Whitman have become controversial. Tate tells how the life and death of Marcus and Narcissa Whitman were used to codify the Northwest as the white man’s territory, American white men in particular. They were early out on the Oregon Trail and helped establish its route. The Whitmans were credited by their contemporaries and historians with bringing the first white women overland to the Northwest and with settling the land not just for their own benefit, but to converting its inhabitants to Christianity. Other whites had settled in the Oregon Country before the Whitmans — the British and French of the Hudson’s Bay Company, for instance, and their workers and traders of many and often mixed races. Historians and Northwest boosters credited the Whitmans with having sparked a flood of emigrants that “saved” the Northwest for white America and “added three stars” to the U.S. flag.

In the late 19th and early 20th century, many in the Northwest began to lionize the generation that settled the country. Hagiographic versions of pioneer history abounded, monuments were raised and reenactments were conducted, as when pioneer Ezra Meeker retraced the Oregon Trail multiple times to enshrine it in American memory. That period coincides with the time advocates of the South lobbied for a history that celebrated the soldiers and politicians of the Confederacy — a time of so-called racial “reconciliation” among whites.

The Whitmans were, as Tate tells it, ineffective missionaries. Their work generated more hostility among the Indigenous people they the targeted for their mission than it won converts or friends. They impressively endured the hardships of settling on the far edges of the frontier, but they never really learned anything from the people they were there to “save.” They never learned Nez Perce, a dialect of which — Weyíiletpuu — was spoken by the Cayuse. They reneged on promises to pay for the land they appropriated, and they staunchly viewed the Native people through the rigid religious lens as souls that needed to be saved from their evil ways. They generally, and fatally, ignored more positive models of relationship that were all around them, including Cayuse practices of relating and resolving conflicts, the examples of comparatively more respectful negotiating and trading behavior by the “King George” men of Britain, and even the somewhat more culturally careful approaches of early Catholic missionaries in the same vicinity. The Whitmans adhered to a strict Christian supremacy that invited resentment, suspicion and anger.

The death of roughly a dozen people in the “massacre” did not come without warning. It was not sanctioned by all members of the tribe. Tate’s account, drawing on the letters and diaries of the Whitmans and their contemporaries, historical documents and tribal history, suggests strongly that the Whitmans, by dint of worldview, personality and behavior, were hardly innocents. Yet in the wake of their deaths, their fellow Oregon Country settlers deemed that they needed to be avenged and turned into Manifest Destiny martyrs. Their deaths served nationalistic expansionism at a key moment in history when overland migration by Americans and immigrants was possible and encouraged by a government seeking to secure the Northwest by occupation against British claims.

The Whitmans, as they have come down to us, are largely fakes. Tate begins by talking about how students at Walla Walla’s Whitman College have pushed back against the Whitman mythos. Someone splashed paint on a portrait of Narcissa, blotting out her face. We later learn that there is no known picture of her; the portrait is simply a work of an artist’s imagination. The same with the famed Marcus Whitman statue in the U.S. Capitol, a macho pioneer in buckskin appearing to lead the way West. Whitman undoubtedly had a good deal of energy and worked hard, but Tate notes that no images of him survive either, that the statue’s bearded face is imagined and that Marcus would likely never have worn buckskins as shown because he considered them “heathenish.” (Referring to his lusty sense of action and confidence, Tate writes that if Statuary Hall “had a hunk contest, he’d be the winner hands down.”)

Part of our history is unremarkable people doing remarkable things, and the Whitmans certainly fit this category. Their sheer energy and sacrifice to set up their mission, to farm, to build, to take in orphans of other settlers or to school the children of mixed race is impressive. This is true of many settlers of less historical importance. But their rigidity of faith and intolerance of racial and cultural diversity proved their undoing. With hindsight, the “massacre” needn’t have happened.

Tate begins with the killings at the mission, then goes back to show what led up to it, not in the tradition of true crime but as a contextual understanding of why this cultural collision took place and how it was used afterwards. The actual history is much more interesting and telling than the images of the saintly Whitmans many of us were fed in Washington state history classes. We deserve better, and so, frankly, do the Whitmans. Tate’s book sets a tone for discussing this in all its complexity. It is fair, well-researched and nicely contextualized. And it includes the vital view from tribal perspectives.

It is timely, too. Last year, Seattle state Sen. Reuven Carlyle proposed that Marcus Whitman’s inclusion as one of two figures in Statuary Hall in the Capitol be reconsidered. Whitman didn’t enter the hall until 1953, the year of Washington’s territorial centennial and more than a century after he and Narcissa were killed. Carlyle’s proposal did not advance, and he says he won‘t reintroduce it this session. But he asks of this history, “How can we have a public conversation?”

He sees Tate’s book as an opportunity to start that dialogue and would like to see a commission that travels the state to seek input about the future of the Whitman statue in Washington, D.C. Another bill that might be in the offing is said to propose substituting the Whitman statue with one of Billy Frank Jr. (Nisqually), the late, much respected Native treaty activist who did so much to advocate for and restore tribal rights.

As historians have pecked away at the mythology, as reckonings have been called for, it seems timely to reconsider whether Whitman truly reflects contemporary values or whether others, like Frank, deserve to be honored in his stead. Surely there have been people who have inspired and achieved in the past nearly 175 years since Whitman’s death who deserve consideration.

Visit crosscut.com/donate to support nonprofit, freely distributed, local journalism.