Police, Reformers Face Off Over Proposal To Ban Chokeholds And Military Equipment In Washington

READ ON

A proposal to impose sweeping restrictions on police tactics and techniques in Washington is highlighting stark differences of opinion between police and reform groups.

That divide was on display Tuesday in the House Public Safety committee during a lengthy, virtual public hearing on an omnibus bill sponsored by Democratic state Rep. Jesse Johnson. His measure, which is co-sponsored by several other Democrats, would ban:

- Chokeholds and neckholds

- The use of unleashed police dogs to effect arrests

- The use of tear gas

- The acquisition and use of military-grade equipment

- Methods to obscure identifiable information on police badges

- No-knock warrants

- Vehicle pursuits except in certain circumstances

- Shooting at a moving vehicle ” class=”wysiwyg-break drupal-content” src=”/sites/all/modules/contrib/wysiwyg/plugins/break/images/spacer.gif” title=”<–break–>”>

In making the case for his legislation, Johnson, who’s the vice chair of the Public Safety committee, said most officers do their jobs “with honor and with respect to the profession.”

But he said systemic racism in society, along with policies that are not uniform across police departments can combine to create “unnecessary violence and tactics.”

“In many cases, bad policing is the result of bad policy,” Johnson said.

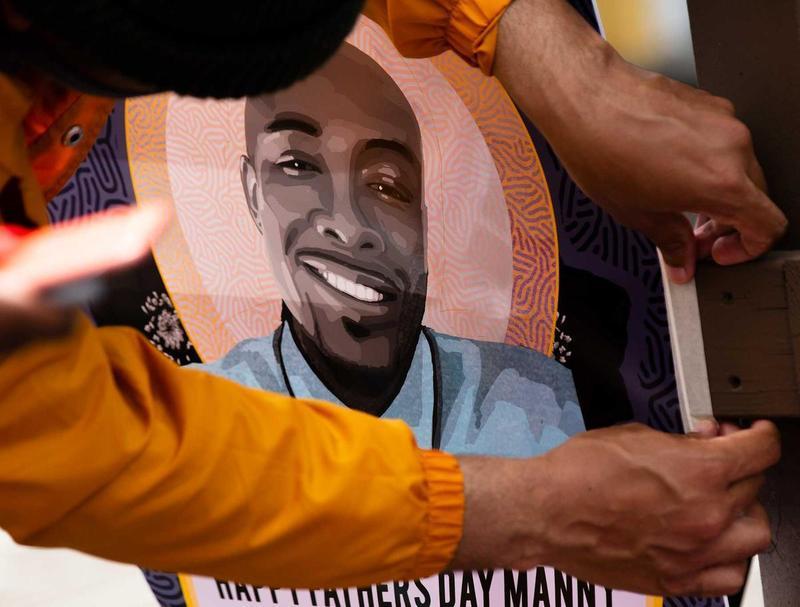

The debate over police accountability in the Washington Legislature follows the death of Manuel Ellis at the hands of Tacoma police in March and the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis in May, which triggered a spring and summer of protests and marches across the country and a conversation about racial justice that’s been described as a national racial reckoning.

On Tuesday morning, in a series of alternating virtual panels, the Public Safety committee heard from groups calling for reform and from police officers and their representatives who mostly expressed wariness — if not outright opposition — to the proposed changes.

Among those testifying were family members of people killed by police. They included Sonia Joseph whose unarmed son Giovann Joseph-McDade was shot and killed by a Kent police officer in 2017 following a chase.

“We need to draw the line on tactics that have been used recklessly like hot pursuits and shooting at moving vehicles,” Joseph said.

Trishandra Pickup of the Suquamish Tribe held up a photo of Stonechild Chiefstick, the father of four of her children, who was shot and killed by a Poulsbo officer in 2019. Pickup noted that Native Americans are killed by police at a higher rate than any other racial or ethnic minorities.

“Please enact this law,” Pickup said tearfully. “We must start to address the history of policing and take off the table those tactics that oppress and demoralize entire communities.”

The committee also heard from Fred Thomas whose unarmed son Leonard was killed by a Lakewood police sniper during a lengthy standoff in 2013. The family later won a civil case against the Lakewood Police Department and ultimately settled for $12.5 million.

“There is no consequence for taking a life if you have a badge,” Thomas said. “This is a culture you are being asked to change.”

Thomas, Pickup and Joseph are all involved with the Washington Coalition for Police Accountability.

Criticism of the measure came from a mix of individual police officers and police organizations, although they were not monolithic in their views. For instance, the Washington Association of Sheriffs and Police Chiefs (WASPC) said it opposed the elimination of all no-knock warrants, while the Washington Fraternal Order of Police said it supports the ban.

There were also nuanced differences between the police groups around the use of chokeholds and neck restraints, as well as other elements of the proposed legislation. At the same time, the police groups indicated a willingness to work with lawmakers on compromise language.

“These issues are important enough for the Legislature to get them right the first time,” said James McMahan of WASPC. “It is the Legislature’s responsibility to ensure that well-intentioned language does not endanger the public or public servants.”

Some of the strongest opposition to the bill came from two Black officers with Teamsters 117. Arman Barros, who is a Port of Seattle officer, invoked the recent attack on the U.S. Capitol in voicing his concern about to requiring police departments to give up military-style hardware.

“Recent events have demonstrated how long from a logistics perspective it can take for National Guard or mutual aid to respond should we need assistance,” Barros said.

Redmond Police detective Aliyyah Slade testified that under the proposal an officer could be criminally charged for restorting to a neck restraint in a fight for their life. She also said that under the bill it would be against the law for an officer to shoot at a car that was being used to mow down civilians.

“Please give further consideration before taking away tools that give police officers time and distance to safely resolve dangerous situations,” Slade said.

Both Slade and Barros spoke as representatives of their union, not their departments.

But Carlos Bratcher, a former King County Sheriff’s deputy who has held leadership roles in state and national Black law enforcement organizations, and is now with the Washington Coalition for Police Accountability, expressed support for the bill and told the committee that it’s time “to take some tactics off of the table.”

Sakara Remmu of the Washington Black Lives Matter alliance offered a stark image of communities of color under siege by police equipped with weapons of war, including tear gas, which is banned by the Geneva Conventions. Specifically, Remmu noted that Seattle police had used tear gas following Blacks Lives Matter protests last spring.

“This year with your leadership and action, Washington state stands poised to lead the nation in creating systems of transparent police accountability and anti-racist statewide alternatives to a police response when a community member needs help, that is the context of this bill,” Remmu said.

As the hearing concluded, the chair of the House Public Safety Committee, Democrat Roger Goodman, predicted that “hours of negotiation” on the details of the bill are yet to come.

The fact that Johnson’s police tactics bill got a hearing on day two of the legislative session is an indication of the high priority that majority Democrats are placing on police accountability this year. In addition to Johnson’s legislation, a dozen or so other police reform measures have been drafted. They include a proposal from Gov. Jay Inslee to create a statewide, independent office to investigate allegations of excessive force.

Related Stories:

Gov. Inslee Signs Police Reform “Fix” Measures

Gov. Jay Inslee, pictured in this file photo, signed two measures that “fix” issues in the state’s police reform laws Listen Read Washington Governor Jay Inslee has signed into law

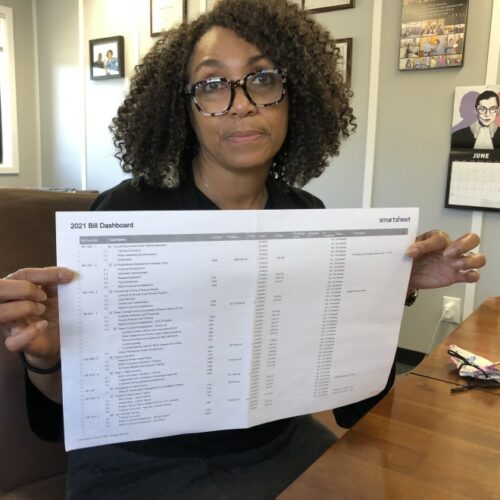

‘Cultural Changes Ahead’ For Police In Washington State, As Controversial Reform Takes Effect

New laws governing Washington State law enforcement took effect on Sunday, including their use of force (HB 1310) and tactics (HB 1054).

Some police departments in King County say new laws means they will no longer respond to certain calls; City of Seattle chief Adrian Diaz calls that “absurd.”

Flanked By Families, Washington Governor Signs A Dozen Police Reform Bills Into Law

Calling it a “moral mandate,” Gov. Jay Inslee on Tuesday signed into law a dozen bills that backers hope will improve policing in Washington, reduce the use of deadly force and ensure that when deadly encounters do occur the investigations are thorough and independent.