Past As Prologue: Remembering A Pasco Civil Rights Protest And Discrimination That Built Tri-Cities

Listen

NOTE: The following essay and its audio component are part of an ongoing series produced in conjunction with the Washington State University history department. The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the author.

In this installment of NWPB’s “Past as Prologue” series, we learn about a protest in Pasco, Washington, against police brutality that happened more than 50 years ago. Robert Franklin, WSU archivist and oral historian at the Hanford History Project, explains what led to that moment.

BY ROBERT FRANKLIN

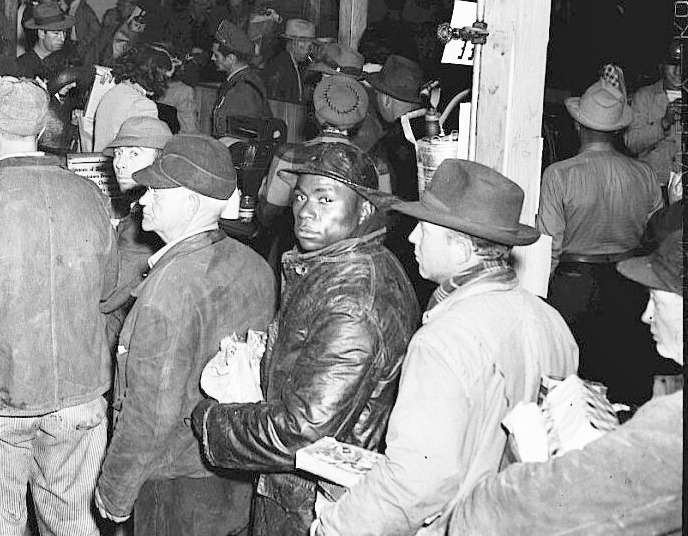

In the summer of 1943, thousands of temporary African American workers were recruited by the Du Pont company to build the secretive Plutonium works. After the war, the expansion of Hanford and the construction of many dams on the Snake and Columbia Rivers again drew thousands of African Americans to the Tri-Cities, but this time to stay.

Robert Franklin, WSU archivist and oral historian at the Hanford History Project

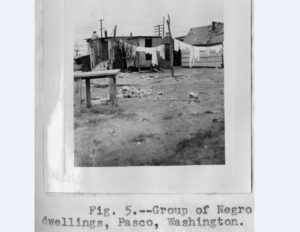

During WWII and after, African Americans could only find living spaces in the dormitories on the Hanford Site or in segregated East Pasco, literally “across the tracks” and connected to Pasco by a dark underpass. By 1950, 20% of Pasco’s approximately 10,000 residents were Black, almost all living in slum conditions. Few lived in the new atomic community of Richland and none in “lily-white” Kennewick — a fact of which Kennewick city leaders and police at the time were proud. Not only was housing segregated, but Black residents were forced to endure broad discrimination in employment and education.

Shack housing for African Americans in Pasco, Washington. Photo from a masters thesis by James Wiley / courtesy of WSU history department

The first of many demonstrations in support of Civil Rights began in Kennewick and Pasco in 1963. Kennewick had been dubbed the “Birmingham of Washington,” alluding to the housing and employment discrimination practiced there. Although as one local pastor noted: “People are saying that Kennewick is worse than Birmingham, for Negroes CAN LIVE in Birmingham.” Most of these protests were peaceful, but in 1969, a group of several hundred high school students gathered in front of the Franklin County Courthouse in Pasco to protest the use of violence and intimidation by police against black residents. Local Civil Rights leader James Pruitt remembered that in the process of arresting four protesters with warrants, one police officer hit two female protesters with a nightstick. The next day, almost 400 protesters, many with weapons, damaged police cars and burned the trees in front of the courthouse.

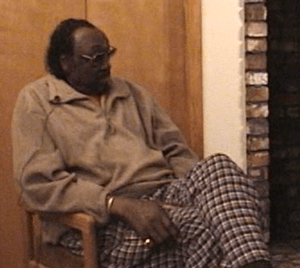

Pruitt recalled: “I got on the wishing well and I cried like a baby. If those kids had pulled out those guns out there and start shooting at them police, they were going to destroy them. And I promised them, if they would just think about it and go back home, I said ‘as long as there is blood in this body, I would never let this happen in this town again. And the kids dispersed.”

Shortly after, Pruitt became the first black employee of Pasco, working in the police and community relations department.

James Pruitt sits for an interview about the riots in Pasco that happened over 50 years ago. Courtesy of the Hanford History Project

This is just one example of addressing inequalities in the Tri-Cities. And there were gains: busing did away with segregated schools, better jobs opened at Hanford, and Urban Renewal replaced much of the blighted East Pasco.

In the upheaval currently roiling our nation, it’s important to understand the successes and failures of the Civil Rights movement in the Pacific Northwest.

While there were gains, many of the injustices and inequalities were not addressed, a fact that we see reflected in the economic disparities by race in our communities, the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement and the recent protests over the killing of unarmed black citizens by our police forces. Clearly, the work of the Civil Rights era is still present and immediate today.

Related Stories:

75 Years After Bombings, Tri-Cities Musician’s Jazz Album Explores Complicated Hanford History

Denin Koch’s trip to the Hanford B Reactor when he was 19 stirred his musical passion. It eventually inspired a full jazz album exploring the complicated history of Hanford, 75 years after the U.S. bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan ended WWII.

Oratorio Performed Inside Hanford’s B Reactor Explores Nuclear Workers’ Dreams And Nightmares

The creators of a new musical work called “Nuclear Dreams” highlight the dreams and nightmares of people who work and live near Hanford in Washington’s Tri-Cities.

Expert Women Explore The Heavy Burden Of Hanford Cleanup In Tri-Cities Event On March 21

PHOTO: Anna King interviewing Jane Hedges, the now-retired head of Washington Ecology’s Hanford office. Hedges grew up swimming off the docks in Richland, but only understood the massive scope of the