‘Brother Robert’ Book Reveals True Story Of Growing Up With Blues Legend Robert Johnson

LISTEN

BY BEN JAMES

Blues legend Robert Johnson has been mythologized as a backwoods loner, his talent the result of selling his soul to the devil. Wrong and wrong again, according to Johnson’s younger stepsister, who lives in Amherst, Mass. She tells his true story in Brother Robert: Growing Up with Robert Johnson, a memoir about growing up with her brother she published in June.

Her name is Annye Anderson, but unless you’re older than she is — and fat chance of that, as she’s 94 — you better call her Mrs. Anderson.

“People say, ‘Don’t you have a first name?'” Anderson says from the couch in her living room. “I say, ‘Yes, I do.’ And they wait for it. But I tell them, ‘Mrs. Anderson will do just fine.'”

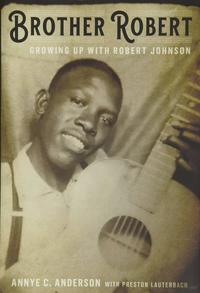

Annye Anderson — stepsister of Robert Johnson — published her memoir Brother Robert: Growing Up with Robert Johnson in June. CREDIT: Ben James

Amherst is a long way from the Memphis of Mrs. Anderson’s childhood, where she grew up in an extended family of siblings, half-siblings and the guitar-playing older stepbrother she called Brother Robert.

“Brother Robert and I used to do the buck dance,” Anderson says. “Because you know he could move. People don’t know. He didn’t just sit and play like they showed him with that caricature.”

Anderson’s childhood — back then she was Annie Spencer — was steeped in the tunes played by Johnson and others, along with all the popular songs they listened to together on the radio.

But before his mysterious death in 1938, Johnson’s “Baby Sis” only ever held one of his records in her hands. It was “Terraplane Blues,” his first release and only record to gain any popularity during his lifetime. After he died, his 29 recorded songs were quickly forgotten.

Anderson became a short order cook, a secretary at the pentagon, a teacher and school administrator. She moved to Washington, D.C. and, later, Massachusetts. In the ’60s, amidst the civil rights movement, she began to hear something familiar on the radio: her brother’s songs.

“During the movement, people were playing his music everywhere and his riffs everywhere,” she says. “Sound familiar, but we didn’t know they were copying from — we didn’t know about Eric Clapton, and Led Zeppelin, and Keith Richards, the Rolling Stones.”

Music and culture critic Greil Marcus has been a fan of Robert Johnson for decades. Now he’s a fan of Anderson. Marcus praises her new book — and Johnson’s artistry — in the New York Review of Books.

“There is something in Robert Johnson’s music that goes beyond, goes above, that is harder, that is deeper, that burrows beneath in ways that other music doesn’t,” Marcus says.

The cover of Brother Robert shows the third known photograph of Johnson, never before seen by the public. Anderson and her older half-sister, who she called Sister Carrie, kept that photo close for decades, storing it in a box that originally held sewing machine oil.

Anderson’s story begins with her family’s roots in Hazlehurst, Miss. — including her first memory of Johnson in Memphis when he swept her up and carried her up a set of steps “like lightning” — and spans the decades after her brother’s death, when a mostly-white audience invented the story of Johnson selling his soul to the devil at the crossroads, a myth that was more racist caricature than anything having to do with his actual life.

“I’m not saying he was an angel,” Anderson says. “And I’m not saying what he didn’t and did do. Because I didn’t have him in my pocket. But people like to be on the dark side. And that’s what they paint. He’s brilliant on one side. And he’s dark on the other. And I deeply resent that.”

The second half of Anderson’s book recounts numerous ways in which she and Sister Carrie were excluded from Johnson’s estate while white music publishers and other opportunists sought to profit from his legacy.

Anderson co-wrote Brother Robert with historian Preston Lauterbach. She sought him out herself, she says, after his book The Chitlin’ Circuit fell at her feet in the music section at her local Barnes & Noble.

“I opened it and then I saw this white face,” Anderson says. “And I said, ‘Well, what does he know about the chitlin’ circuit?'”

She bought the book and read most of it that same night, deciding she needed Lauterbach’s help in her ambition to correct the record on the life of Robert Johnson. Anderson talked about the book for years, never believing that it would exist one day.

“She felt that the story had been told badly by outsiders for long enough,” says Elijah Wald, author of Escaping the Delta: Robert Johnson and the Invention of the Blues. “And she wanted to tell the story herself.”

Wald, who wrote the introduction to Brother Robert, says Anderson’s book offers a necessary corrective to the image of Johnson as a backwoods loner playing primal and haunted music.

“Robert Johnson was as much the guy from Memphis who went out in the country and was the hip city guy as he ever was the guy from the dark Delta who went up to the cities,” he says.

Marcus concurs, saying what stands out most in Brother Robert is the sheer range of American popular music flooding through Anderson’s story. A couple pages in, he says, he started making a list of songs the family listened to or played.

“And the list just grew and grew until there were maybe 20, 30, 40 different examples. And I realized no one could have a richer, broader, more mainstream American cultural life than the one that Robert Johnson lived out,” Marcus says.

Some of Anderson’s favorites included The Vagabonds, Gene Autry, Clyde McCoy now, Count Basie, Fiddlin’ John Carson, Bing Crosby and Louis Armstrong.

“Brother Robert is the one that got me into country music,” she says. “‘Course, Jimmie Rodgers was his favorite. I will never forget ‘Waiting for a Train’ and doing it with Brother Robert.”

The two would bust up laughing at the line “Get off, get off, you railroad bums.” And then came Rogers’ famous yodel.

“I tried to yodel,” Anderson says. “But brother Robert could yodel. He could mimic anything.”

In the memoir there’s a moment, toward the end of Johnson’s life, when a young Anderson walks her brother to a spot on Highway 61 so he can hitch a ride across the Mississippi. He smelled of cigarettes, Anderson writes, and Dixie Peach pomade:

“He would say, ‘Well, little girl, this is far as you could go,’ Because I wasn’t supposed to go but so far. He’d give me a hug — ‘Bye Little Sis’ — and tell me to go straight home.”

Many of Johnson’s fans would likely sell their own souls to be able to follow him down that highway to his next house party and to hear his version of “Waiting for a Train.” Instead, they’ve got his 29 recorded songs. And now they have Anderson’s memoir.