In Historic Move, Rep. Deb Haaland Will Be Nominated As First Native American To Lead Interior

LISTEN

BY NATHAN ROTT

In a historic first, President-elect Joe Biden will nominate Rep. Deb Haaland to lead the Department of the Interior, his transition team announced Thursday evening.

If confirmed by the Senate, Haaland, a member of the Laguna Pueblo in New Mexico, would be the country’s first Native American Cabinet secretary. Fittingly, she’d do so as head of the agency responsible for not only managing the nation’s public lands but also honoring its treaties with the Indigenous people from whom those lands were taken.

In a statement, the Biden-Harris transition team called Haaland a “barrier-breaking public servant who has spent her career fighting for families, including in Tribal Nations, rural communities, and communities of color,” who will be “ready on day one to protect our environment and fight for a clean energy future.”

In a tweet, Haaland acknowledged the unique “voice” she’ll bring. “Growing up in my mother’s Pueblo household made me fierce,” she wrote. “I’ll be fierce for all of us, our planet, and all of our protected land.”

“She understands at a very real level — at a generational level, in her case going back 30 generations — what it is to care for American lands,” says Aaron Weiss, deputy director of the Center for Western Priorities.

A voice like mine has never been a Cabinet secretary or at the head of the Department of Interior.

Growing up in my mother’s Pueblo household made me fierce. I’ll be fierce for all of us, our planet, and all of our protected land.

I am honored and ready to serve.— Deb Haaland (@DebHaalandNM) December 18, 2020

Haaland’s nomination is a win for tribal governments, environmental groups and some progressive lawmakers who had been lobbying for the New Mexico lawmaker to lead the Department of the Interior. Her fellow House Natural Resources Committee member and rumored Interior candidate, Rep. Raúl Grijalva, D-Ariz., wrote a letter to the Congressional Hispanic Caucus recommending Haaland for the post.

“It is well past time that an Indigenous person brings history full circle at the Department of Interior,” he wrote.

It’s not the first time Haaland has made history. In 2018, she became one of the first two Native women in Congress, alongside Rep. Sharice Davids of Kansas.

The Interior Department upholds the federal government’s responsibilities to the country’s 574 federally recognized Indian tribes and Alaska Native villages. Its roughly 70,000-person staff also oversees one-fifth of all the land in the U.S. as well as 1.7 billion acres of the country’s coasts. It manages national parks, wildlife refuges and other public lands, protecting biologically and culturally important sites while also shepherding natural resource development.

The Biden administration is expected to take a much different approach to natural resources than its predecessor, which championed oil and gas development above all else on federal lands. Biden has promised to shift the U.S. away from climate-warming fossil fuels toward renewable energy sources such as wind and solar.

Deb Haaland worked on President Obama’s 2008 campaign before chairing New Mexico’s Democratic Party. Now she’s running for office with a record number of other Native Americans across the country. CREDIT: Juan Lebreche/AP

In an interview before her nomination, Haaland told NPR that would be her priority, too.

“Climate change is the challenge of our lifetime, and it’s imperative that we invest in an equitable, renewable energy economy,” she said.

A shift in priorities at Interior could have major implications for global climate change and the United States’ outsized contribution to it. About one-quarter of all U.S. carbon emissions come from fossil fuels extracted on public lands, according to the U.S. Geological Survey. That includes emissions from drilling, transporting and refining those fossil fuels before they’re burned.

Haaland’s experience as a lawmaker in fossil fuel-dependent New Mexico, and as the former head of the state’s Democratic Party, leaves her well-positioned to navigate that transition, environmental advocates say. The state has one of the most aggressive climate plans in the country.

“You have to understand the complexity of public lands management,” says Demis Foster, executive director of Conservation Voters New Mexico. “And I can’t imagine a better representation of that than here in New Mexico. We have a vast network of public lands. We have extraordinary biodiversity, and we have a very unique cultural heritage.”

State lawmakers also have to balance that, she says, with the “extraordinary force and influence of extractive industry.”

The New Mexico Oil & Gas Association called on Haaland to take a “balanced approach.”

“Responsible energy development on federal lands is a vital part of our state’s economy,” the group said in a statement. “The policies enacted by the next Interior Secretary,” it said, “will determine how much or little our state is able to support critical needs like public schools, healthcare, and first responders.”

Mike Sommers, chief executive of the American Petroleum Institute, said in a statement that oil and gas resources “will be critical to rebuilding our economy and maintaining America’s status as a global energy leader.”

Haaland has echoed Biden in saying that a transition to renewable energy is a job creator, which makes it a no-brainer during the economic uncertainty spurred by the ongoing coronavirus pandemic.

She’s also sponsored a House bill that would set a national goal of protecting 30% of U.S. lands and oceans by 2030, a plan the Biden administration has adopted and made a priority for his environmental agenda.

“That would protect our wildlife and boost the restoration economy,” Haaland said, and “undo some of the damage that this Trump administration has done to our environment.”

The Biden administration has promised to undo a number of environmental rollbacks undertaken over the past four years, and Interior will play a key role.

President Trump leaned on the agency to help push his broader “energy dominance” agenda. The agency’s current leader, Secretary David Bernhardt, is a former oil and energy lobbyist. His predecessor, Ryan Zinke, a former congressman from Montana, resigned amid numerous ethics investigations.

Under their leadership, national monuments were cleaved, opening up millions of acres of formally protected land to development. Millions of acres more — onshore and offshore — were made available for oil and gas leasing. Regulations were rolled back on methane emissions and imperiled species protections, among others.

Haaland was a vocal critic of many of those moves. As chair of a House Natural Resources subcommittee that oversees Interior, she has led hearings on everything from the Trump administration’s handling of national park reopenings during the coronavirus pandemic to its treaty-obligated communications with tribal governments for projects that affect their lands.

“Tribal consultation is basically nonexistent during this Trump administration,” Haaland said. “President-elect Biden has promised to consult with tribes, which I think will help immensely with some of the environmental issues that he wants to address.”

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change found that Indigenous people are disproportionately vulnerable to climate change in the United States. Alaska Native villagers and a Native American community in south Louisiana are among the first climate refugees in the country. Both are being relocated due to rising seas.

Indigenous people are also disproportionately affected by environmental pollution, says Kandi White, the Native energy and climate campaign director at the Indigenous Environmental Network.

“Fossil fuel development, uranium development, clear-cutting of forests — all these things that have been happening on tribal lands were exacerbated under the [Trump] administration and need to be looked at,” she says.

As a member of the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation in North Dakota, White says, she’s seen the effects of fracking and other development firsthand.

She thinks it will be impactful to have a Native American woman such as Haaland, who understands the complex government-to-government relationship between Indigenous people and the U.S., leading the Department of the Interior.

“She gets it,” White says.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit npr.org

Related Stories:

Yakama descendants search for relatives’ remains at Mool-Mool, or Fort Simcoe Historical State Park

WATCH Listen (Runtime 4:15) Read Editor’s Note: This report is a collaboration between the Northwest News Network, Northwest Public Broadcasting and the Yakima Herald-Republic. A cultural edit was provided by

U.S. Department of Interior launches program to preserve Indian boarding school oral histories

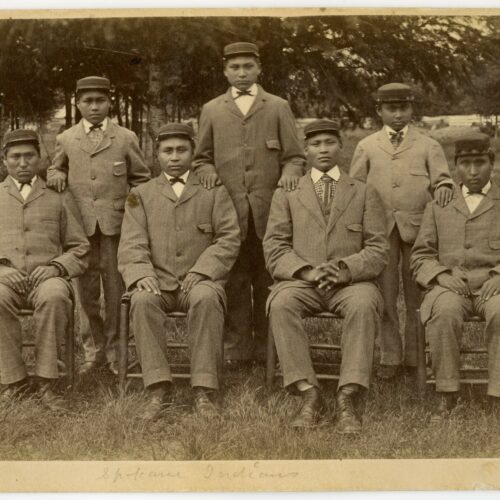

This historical photo, provided to Oregon Public Broadcasting by Pacific University archivist Eva Guggemos, shows seven boys who came to the Forest Grove Indian Training School from the Spokane Tribe

Interior Department Initiative Means A Closer Look At Northwest Indigenous School Burial Sites

When Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland announced a sweeping investigation into burial sites on current and former school sites that have historically served Native Americans, it was met with amazement, even among people who’ve been searching out Indigenous remains for years.