In His 250th Year, Beethoven’s Legacy Is One Of Life, Liberty And Pursuit Of Enlightenment

LISTEN

BY TOM HUIZENGA

Two-hundred-fifty years ago, a musical maverick was born. Ludwig van Beethoven charted a powerful new course in music. His ideas may have been rooted in the work of European predecessors Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Josef Haydn, but the iconic German composer became who he was with the help of some familiar American values: life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. That phrase, from the Declaration of Independence, is right out of the playbook of the Enlightenment, the philosophical movement that shook Europe in the 18th century.

“One way to look at it is what happened after Newton created the scientific revolution: Basically, people, for the first time, developed the idea that through reason and science, we can understand the universe and understand ourselves,” says Jan Swafford, the author of Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph, a 1,000-page biography of the composer.

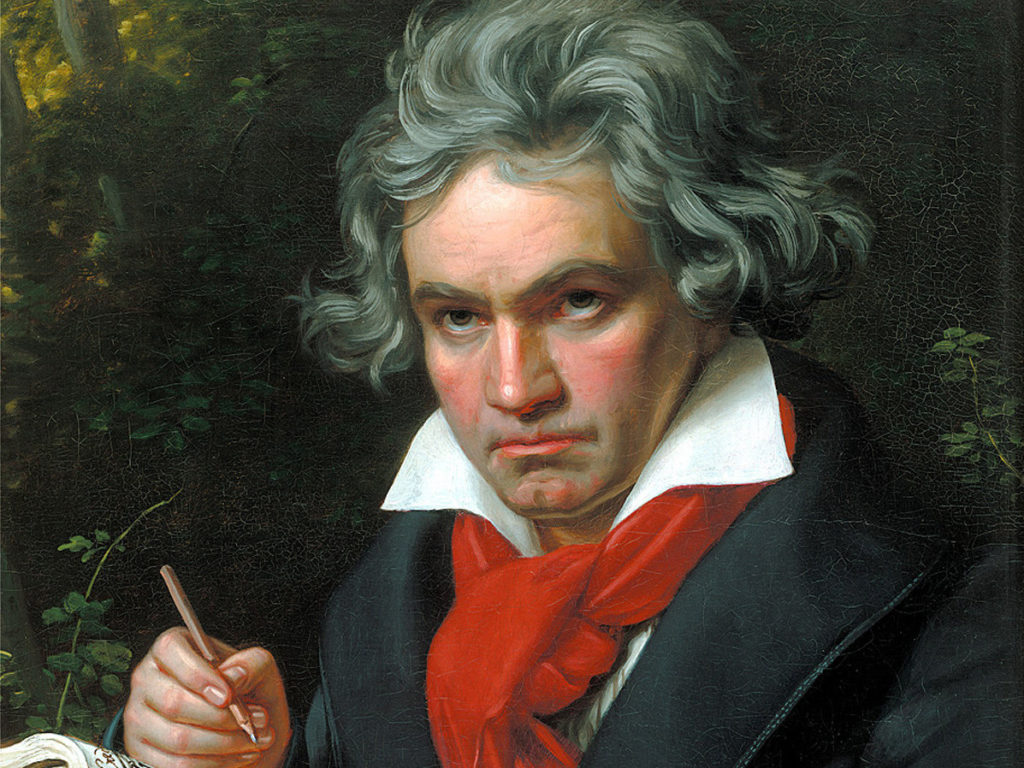

Portrait of Beethoven by Joseph Karl Stieler, ca. 1818. CREDIT: Wikimedia Commons

Swafford says the Enlightenment idea embodied in the Declaration of Independence is that the aim of life is to serve your own needs and your own happiness. “But you can only do that in a free society,” he says. “So freedom is the first requirement of happiness.”

Other key components of the Enlightenment — including a cult of personal freedom and the importance of heroes — were vibrating in the air in Beethoven’s progressive hometown of Bonn when he was an impressionable teenager. “There was discussion of all these ideas in coffeehouses and wine bars and everywhere,” Swafford adds. “Beethoven was absorbed into all that and he soaked it up like a sponge.”

You can hear ideas from the Enlightenment in Beethoven’s Third Symphony, nicknamed “Eroica” — heroic. “There’s an amazing place near the end of the first movement of the ‘Eroica’ where you hear this theme which I think represents the hero,” Swafford points out. “It starts playing in a horn, and then it’s as if it leads the whole orchestra into a gigantic proclamation, as if that is the hero leading an army into the future.”

The hero of the “Eroica” Symphony was originally Napoleon — until Beethoven found out he was just another brutal dictator, and tore up the dedication page of the score. Overall, the hero of much of Beethoven’s music is humanity itself.

“He was a humanist, above all,” says conductor Marin Alsop, who had planned to mount Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony on six continents this year, before the pandemic hit. Beethoven, she says, believed that each of us can surmount any obstacle.

“You can hear his perspective on this new philosophy of the Enlightenment, because it’s very personal to Beethoven,” Alsop says. “Throughout all of his works, you have this sense of overcoming.”

You can hear that journey from darkness to light in pieces like the “Eroica,” in the famous Fifth Symphony — and, Alsop says, at the very beginning the groundbreaking Ninth Symphony.

“It opens in the most unexpected way for a piece that’s about to make a huge statement,” Alsop says. “You can’t even tell if it’s a major or a minor key. It’s kind of fluttering with a tremolo sound in the strings. It’s this idea of possibility, an empty slate.”

From there, Alsop adds, “Beethoven builds this whole journey of empowerment of unity. There’s a lot of unison where the orchestra shouts out as one.”

Those unisons are the way Beethoven depicts the connections between people – a pretty important thing for a man who began to go deaf before he was 30. He’s a perfect symbol for this era of COVID, Alsop says, because of his severe isolation. That solitude sent the composer out for long walks in the woods outside Vienna.

“Beethoven absolutely loved and cherished nature, and thought of nature as a holy thing,” says conductor Roderick Cox, who led performances of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 6, the “Pastorale,” this fall in Fort Worth, Texas. “Those are some of the principles of Enlightenment, of this music, the liberation of the human mind.”

Cox also points to another Beethoven obsession: freedom, which is captured on stage, he says, in the composer’s politically fueled opera Fidelio. “It really is the epitome of this Enlightenment spirit: This governmental prisoner, speaking out against the government for individual rights and liberty, has been jailed.” In the opera, when the chorus of political prisoners leave their dungeon cells for a momentary breath of fresh air, Beethoven has them sing the word “Freiheit” — freedom.

Two and a half centuries after his birth, Beethoven continues to loom large over today’s composers — literally, in some cases. American composer Joan Tower has a picture of Beethoven over her desk, and says he even paid her a ghostly visit once while she was trying to write music.

“He walked into the room right away,” Tower says,” and I said, ‘Listen, could you leave? I’m busy here.’ He would not leave. So I said, ‘OK, if you’re going to stay, then I’m going to use your music.’ ” And she did, in her piano concerto: Dedicated to Beethoven, the piece borrows fragments from three of his piano sonatas, including his final sonata, No. 32 in C minor.