‘Hold Their Feet To the Fire’: Getting A COVID-19 Vaccine To Hard-Hit Native Communities

LISTEN

BY KIRK SIEGLER

These last few days have been chaotic at the Nimiipuu Health Clinic on the Nez Perce Reservation in Idaho.

The director, Dr. R. Kim Hartwig, is trying to manage testing and treating patients for COVID- 19 and other diseases, while also racing to get a plan in place to distribute a vaccine.

“It’s not something that we have a timeline [for], it’s like, I got a call and was told, ‘You’re gonna get a vaccine in two weeks, get a plan together,’ ” she says.

Only a handful of Hartwig’s frontline workers are expected to get the initial Pfizer vaccine because the tribe doesn’t have the special refrigeration and storage it requires. But she’s OK with waiting a few more weeks for the expected second Moderna vaccine that won’t need that. It’s a feat in and of itself to be getting a vaccine this fast to rural Lapwai, Idaho, population 1,000.

Tribal leaders on the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota say they plan to hold the Indian Health Service accountable as the first vaccines are set to be delivered to Indian Country.

CREDIT: Kirk Siegler/NPR

“I’m thankful for that,” Hartwig says. “If I have to scramble some to make sure my community is safe, that’s what I’ve committed my life to.”

The federal government has designated an allocation of the first coronavirus vaccines to hard-hit Indian Country. Native Americans have long endured health care inequities, and they’re four times as likely to be hospitalized by COVID-19.

Still, reaching everyone who needs it will be a monumental challenge, and there is plenty of skepticism about the federal government’s ability to deliver, after a century’s worth of broken treaties and failures to meet government to government obligations with sovereign tribes.

“We’re treating this as any other challenges we’re faced with,” says Commander Andrea Klimo of the Indian Health Service.

Tribes had the option of getting the vaccine shipments from their state or the IHS. More than half of the 574 federally recognized tribes are doing what the Nez Perce are, and opting for the IHS, says Klimo.

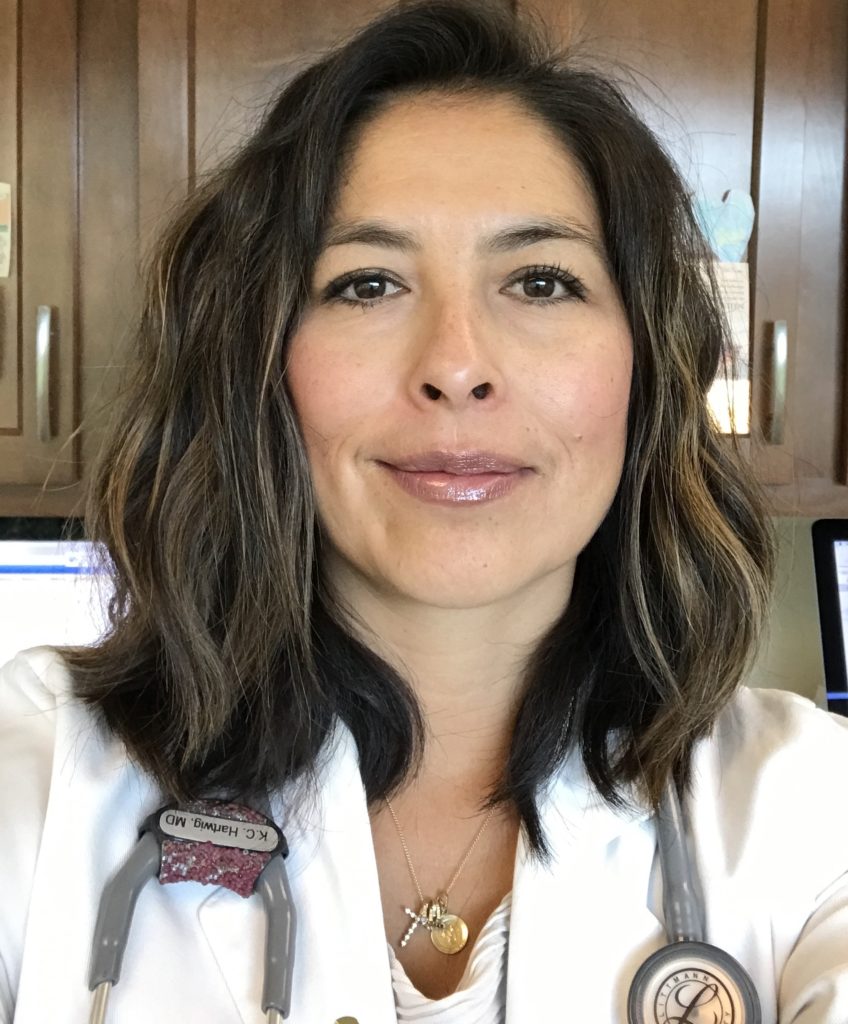

On the Nez Perce Reservation, Dr. R. Kim Hartwig is scrambling to manage testing and treating patients for COVID-19 and other health issues, while also racing to get a vaccine distribution plan in place. CREDIT: R. Kim Hartwig

Klimo, an enrolled member of the Chickasaw Nation in Oklahoma, is leading the government’s task force in charge of distributing the vaccines to tribes.

“We’re tackling it head-on and working through things such as hesitancy or any sort of perceived trust issue, as they come along,” Klimo says.

There will be a lot of scrutiny on the IHS as the first vaccines are expected to begin being distributed in the next couple of days. Congress has long underfunded tribal health care, and consequently, Native people aren’t always confident in the IHS’s ability to deliver.

“We’re going to hold their feet to the fire because it’s their trust responsibility, their treaty obligation,” says Rodney Bordeaux, president of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe.

At the IHS hospital in Rosebud, S.D., only 10 of the 30 beds are even being used right now because of staff shortages. The tribe has had some of the highest COVID-19 rates of infection in the region. Curfews, mask mandates and other lockdowns have been enforced, Bordeaux says, unlike in the surrounding state.

If the IHS fails to distribute the vaccine as planned, Bordeaux says that hopefully, Congress will provide another round of stimulus as a backup.

“It’s very bad, we’ve tried working with Congress to get more funding, but we have not [yet] been able to do that,” he says.

Already CARES Act funds helped pay for mobile units that his tribe will use to deliver the vaccine to communities across its 2,000-square-mile reservation.