Think Health Care Workers Are Tested Often For COVID-19? Think Again

LISTEN

BY LAUREL WAMSLEY

In a recent roundtable with Joe Biden, nurse Mary Turner told the president-elect something he found surprising:

“Do you know that I have not been tested yet?” said Turner, who is president of the Minnesota Nurses Association. “And I have been on the front lines of the ICU since February.”

“You’re kidding me!” Biden replied.

She wasn’t kidding.

Guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggests that health care personnel be tested if they are symptomatic or have a known exposure to the coronavirus. But treating COVID-19 patients while wearing personal protective equipment doesn’t count as exposure that warrants testing.

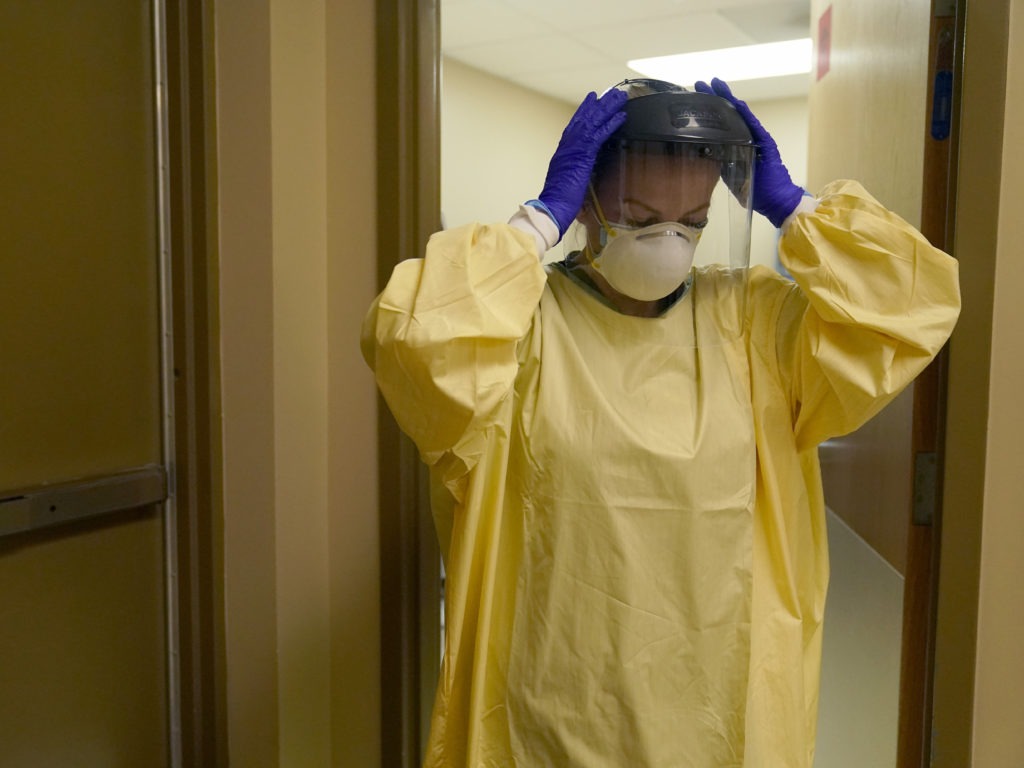

A nurse puts on personal protective equipment last month as she prepares to treat a COVID-19 patient last month at a rural Missouri hospital.

CREDIT: Jeff Roberson/AP

A recent survey by National Nurses United, the nation’s largest union of registered nurses, found just 42% of registered nurses in hospitals said they had ever been tested for the virus.

“It continues to amaze me that we are not doing this,” says Michael Mina, an epidemiologist at the Harvard School of Public Health. While personal protective equipment goes a long way toward protecting health care workers, he says, there have been outbreaks at hospitals.

At Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, where Mina runs the virology lab, an outbreak this fall infected 42 employees and 15 patients. The hospital said factors in the outbreak included patients not wearing masks, staff not wearing eye protection and employees failing to social distance while eating.

But Mina believes that with more testing, the virus would not have spread so widely.

“That is an outbreak that shouldn’t have happened. I believe pretty firmly that we would not have seen an outbreak grow so, so quickly — and it wouldn’t have even been able to get started if we were doing frequent testing.”

Defining the risk

Mina says to imagine a physician at a hospital who has the virus but is asymptomatic. The doctor doesn’t realize he or she has been exposed, and is now working when he or she is most infectious.

“They pose a very serious risk,” Mina says. “At some point in the day, you’re taking off your mask to eat lunch. If you’re eating lunch in a cafeteria, you might expose 10 people without knowing it — especially in a hospital setting where you could have vulnerable people all around you.”

Ideally, he says, people are wearing masks and social distancing. But especially with the arrival of winter, more things are happening indoors. “People are going to have to eat. Whether it’s in a break-room or a cafeteria, you really do run a risk of getting other people exposed.”

Nancy Foster, the American Hospital Association‘s vice president of quality and patient safety policy, says hospitals are following the CDC’s scientific guidance.

“These strategies were put into effect in the early days of the pandemic, when there were persistent concerns about shortages of testing kits and supplies. Hospital staff and the CDC did not want to divert available testing supplies away from patients and the general population,” Foster said in a statement to NPR, adding that the AHA continues to urge the federal government to increase the supply of PPE and testing supplies.

Maggie McGillick, a spokesperson for the American College of Emergency Physicians, says masks and PPE offer strong protection.

“It is nearly impossible to transmit virus through an N95 mask, [Powered Air Purifying Respirators], or other devices,” she wrote in an email to NPR. “Those who do not have close contact routinely wear masks. Handwashing and the use of gloves is part of their routine, so it is very rare for an infected health care professional to transmit the disease to anyone at work.”

‘The precautions and personal protective equipment are working’

Many health care workers are contracting the virus via community spread, just like other Americans. Last month, the Mayo Clinic said that more than 900 employees in Minnesota and Wisconsin had gotten COVID-19 in the previous two weeks, out of its 55,000 staff members there.

Mayo Clinic’s medical director for occupational health, Laura Breeher, says the primary source of exposure for infected staff members is a known exposure to someone at home.

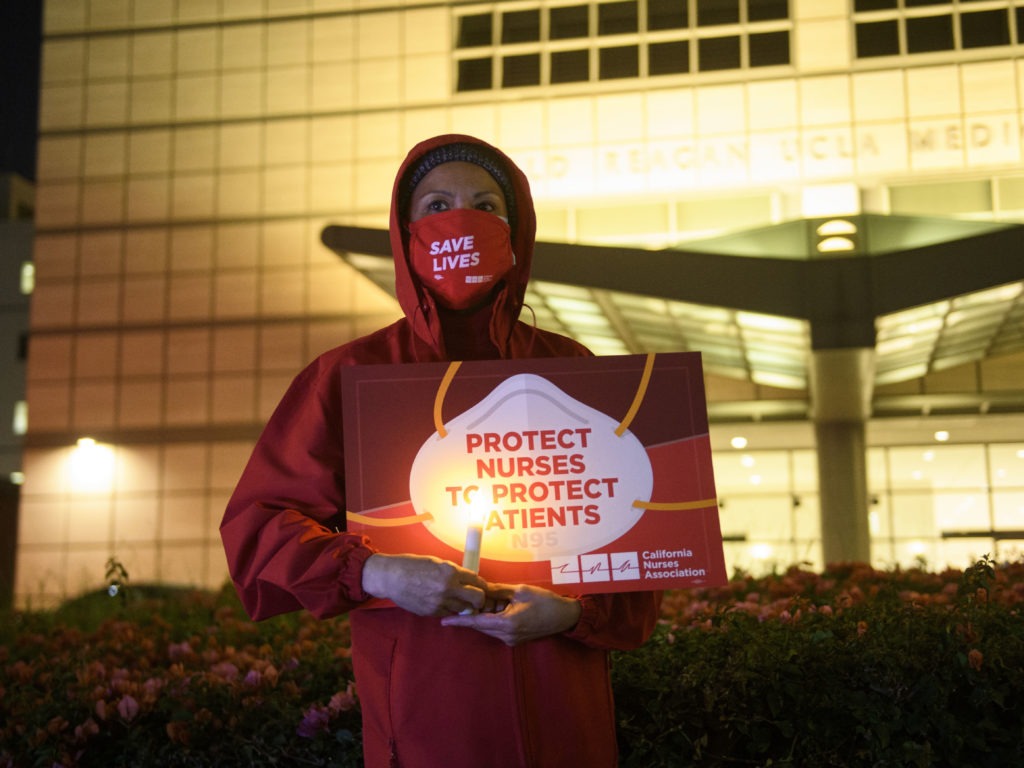

A nurse holds a candle during a vigil in Los Angeles last month for health care workers who have died from COVID-19. The vigil was organized by California Nurses United. CREDIT: Patrick T. Fallon/AFP via Getty Images

How does the clinic know the virus isn’t spreading among staff?

“We track the source for infections very carefully,” Breeher says – and she says the infection rate of the clinic’s health care workers working on-campus in patient care roles is very similar to that of on-campus staff not working with patients and those who are working from home.

“So that’s very, very reassuring to us that the precautions and personal protective equipment are working,” Breeher says.

Many hospitals now require patients to test negative for the coronavirus in the few days before an inpatient procedure. Physicians and nurses themselves, meanwhile, are unlikely to have been tested before conducting the procedure.

Why the different standards?

Breeher says it’s because for many procedures, patients can’t be masked.

She says many patients “are needing procedures that increase risk, such as being on CPAP machines at night or things like that. So we want to make sure that we keep our health care campuses as safe as possible.”

Screening health care workers at scale

Mina, the Harvard epidemiologist, says there are methods that hospitals could be using to do regular testing of large numbers of health care workers– either by using rapid antigen tests or pooling PCR tests.

“They could have everyone swab and put 50 swabs at a time into one tube and run that one tube and pool the tests for very, very cheap. You could do whole hospital departments with one test for 50 bucks a day,” he says. If the pool tests positive, the hospital can then go back and test the people in it individually to see who has the virus.

And rapid antigen tests could work even better: “They only detect people when they’re infectious.”

Mina says that could make antigen tests an ideal choice for screening purposes, because some people continue to test positive on PCR tests for many weeks after they’ve stopped being infectious. That could help hospitals already stretched thin on staffing.

“Many people are only infectious, say, for four days. So maybe [with antigen testing] you come back to work after two days of being negative. Maybe it’s only a five- or six-day isolation,” Mina says.

In California, new guidance ‘strongly recommends’ weekly testing

California’s state health department announced new guidance two weeks ago that strongly recommends hospitals do weekly testing of health care personnel – and suggests pooled testing might be a way to do it.

But Susan Butler-Wu, associate professor of clinical pathology at USC and director of the clinical microbiology lab at a large hospital in Los Angeles, says the state’s new recommendations are going to be very hard for most hospital labs to implement.

Nurses assist a COVID-19 patient at a Los Angeles hospital last month. The California Department of Health now “strongly recommends” hospitals test all of their health care personnel for the coronavirus each week. CREDIT: Jae C. Hong/AP

At her own hospital, she estimates that 10,000 people would need to be tested weekly. Without operational support from the state, she predicts the new protocols are going to cause problems — including further delays in testing.

“When you get some big mandate that, ‘Hey, test all the health care workers in your hospital,’ I don’t have a bunch of pixies with magic swabs and magic reagents that will just magically run this,” Butler-Wu says.

The guidelines could also create staffing shortages, Butler-Wu says, if employees who recently had COVID-19 asymptomatically suddenly get positive PCR tests.

“They may not be infectious, but now what do we do? We tell them to isolate. Now we lose a whole bunch of stuff as a result of that,” she says. “We’re asking people to stay home and not work when they’re truly essential and may not even be an infectious risk to anybody.”

The larger problem is a systemic one, says Butler-Wu.

“As a country, because we don’t have a national plan or a national strategy, this is the situation we find ourselves: Football players can get tests,” she says. “People choosing to socialize and wanting to feel safer doing so, even though it’s a pandemic, can get tests.”

But a national program to regularly test the country’s health care workers? There isn’t one.

Anne Jackson is a nurse at the University of Michigan health system. She says it’s frustrating to read about how the university’s football players and coaches are tested daily, while hospital staff are only tested if they’re symptomatic or have a CDC-defined exposure. (The university also has a surveillance testing program that is open to staff who want to be tested.)

“Football makes them money,” Jackson says. “The health system employees do as well, but not to the extent that the football players do, and the football players are more valuable to them than we are.”

For Mina, the Harvard epidemiologist, the lack of regular testing of health care workers raises other questions.

“There’s a clear problem when we’re saying that the greatest-risk people, the people who are at the greatest risk to themselves and to their patients are the health care workers,” Mina says. “And so that’s why we’re going to give them vaccines before anyone else. But then when we don’t have a vaccine and it’s just testing, we say, ‘Don’t worry about it, it’s not a big deal, you don’t need to be tested.’ ”

It’s an approach, he says, that doesn’t make sense.

Will Stone contributed to this report.