New Documentary ‘Billie’ Explores Mysteries Of Billie Holiday And Her Biographer

LISTEN

BY ELIZABETH BLAIR

Billie Holiday‘s life and artistry have been analyzed, scrutinized, interpreted and embellished more than any other jazz singer in history. But the first biographer to fully immerse herself in the world of Lady Day was a New York journalist and avid Holiday fan named Linda Lipnack Kuehl. For some eight years in the 1970s, Kuehl interviewed everyone she could find who had a personal association with Holiday — musicians, managers, childhood friends, lovers and FBI agents among them. Then, before she could finish her biography, Kuehl died: In 1978, her body was found on a Washington, D.C. street. Her death was ruled a suicide.

Billie Holiday performs in New York City in 1947.

CREDIT: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Kuehl left behind a trove of notes, transcripts and some 200 hours of interviews on cassette tapes — mostly in shoeboxes, some labeled, some not. That archive is where director James Erskine first began pulling together the story Kuehl was never able to finish. His new documentary, Billie (out Dec. 4 on VOD and in select theaters), is about both Holiday — as told through the voices of people who knew her — and Kuehl’s obsession with crafting her biography.

“I’d like to write something that is real,” we hear Kuehl tell one of her interviewees in the film, “that is really Lady Day, and people who don’t see her in any sentimental way, you know? Really, as she is.”

Erskine describes Kuehl as “a brilliant interviewer” who tracked down everybody from various stages of Holiday’s life. “What was extraordinary was it felt like an archaeological journey,” he says, “because it felt like we were excavating voices lost to the past.” Those now-deceased jazz voices include Count Basie, Charles Mingus, John Hammond, Jo Jones and Sylvia Syms.

“She excited me with just three notes,” drummer Roy Harte tells Kuehl. “She looked like a panther. It’s the only way I can describe it. With the most unbelievable face in the world,” marvels Syms, singer and Holiday’s friend.

Before her death in 1978, Linda Lipnack Kuehl spent eight years trying to write the definitive biography of Billie Holiday.

Courtesy of Kuehl’s sister Myra Luftman

To give the documentary a cohesive structure — and to make sense out of the 200 hours of interview material — Erskine says, “We had a discipline that people speaking in the film should only be speaking about an event that they actually witnessed … because otherwise the material was just sort of overwhelming.”

One of most provocative moments in the documentary is Kuehl speaking with Jones, a jazz drummer who toured the country with Holiday when they were both in Basie’s band. Jones questions whether Kuehl, a white woman, is capable of understanding the racism they faced.

“Miss Billie Holiday didn’t have the privilege of using a toilet. The boys at least could go out in the woods,” Jones tells Kuehl. “You don’t know anything about it because you never had to subjugate yourself to it. Never.”

For Farah Jasmine Griffin, author of If You Can’t Be Free, Be a Mystery: In Search of Billie Holiday, Kuehl’s interview with Jones is “extraordinary.”

“I found his passion, his truth-telling, all of his wisdom … his honesty, his courage — I found him so compelling,” Griffin says. “And I was very happy that the filmmakers gave him as much space as they did.”

The film reaffirms some oft-told legends about Billie Holiday: She could curse up a storm; had affairs with men and women (according to some, Tallulah Bankhead among them); liked to get high from cannabis, heroin and cocaine; and often surrounded herself with men who treated her horribly.

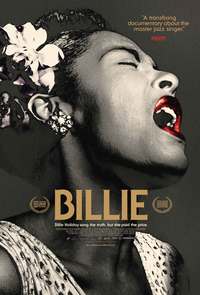

Billie, directed by James Erskine.

We’re also reminded that when Holiday sang “Strange Fruit,” she was “fighting inequality before Martin Luther King, Jr,” as Mingus puts it. (Holiday sang the haunting indictment of lynching to white and Black audiences as early as 1939.) Mingus tells Kuehl, “That might be why the cops were against her. Not just junk” — alluding to Holiday’s arrest, in 1947, for narcotics possession, another event in Holiday’s life that Kuehl probed.

In her interview with Jimmy Fletcher, the narcotics agent assigned to conduct surveillance of Holiday, Kuehl asks him whether a big star like Holiday “would have been a target because it would have been a lot of publicity for an agent.” Fletcher concedes, “Well, not just for an agent. For the Bureau of Narcotics.”

For Erskine, Kuehl’s tireless efforts to uncover the truth about Holiday lead to all kinds of revelations. “You certainly get the sense that the more interviews Linda did, the closer she did get to this sort of underground, seedy world,” he says. In the documentary, Kuehl’s sister says the family does not believe she died by suicide. Erskine isn’t sure. “You do start to wonder,” he says, “if she was maybe doing a lot more than just uncovering Billie’s life, but also the political forces that wanted to silence her.”