Washington Voters Said ‘No’ To A Constitutional Amendment. Now There’s A $15 Billion Problem

LISTEN

In an election year with big races on the ballot, including president and governor, Washington voters – and news media – might have been forgiven for not paying much attention to Engrossed Senate Joint Resolution (ESJR) 8212 on the November ballot.

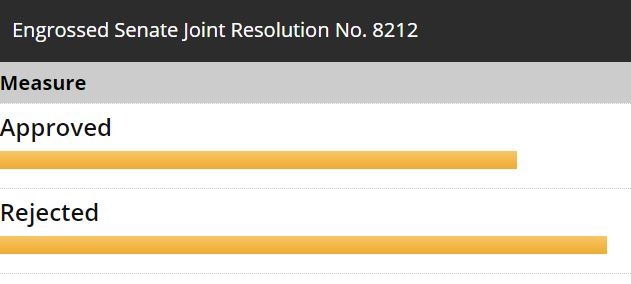

It was a little-noticed constitutional amendment to allow for the investment of long-term care trust fund dollars in private stocks. Voters soundly defeated the measure 54 to 46%.

Now comes the surprise cost of that under-the-radar vote: an estimated $15 billion.

That’s the trust fund’s projected liability over the next 75 years if the funds can’t be invested in the stock market, which would presumably produce larger returns than fixed-income securities like government bonds and CDs.

Washington voters rejected a little-noticed constitutional amendment on the November ballot. As a result, the state’s new long-term care program faces a $15 billion shortfall over the life of the program.

“Put another way, in today’s dollars, the program is expected to require an additional $15 billion of revenue to cover the next 75 years of benefits and expenses,” wrote State Actuary Matt Smith in a post-election analysis of the situation.

It’s a setback for a yet-to-be-launched program that’s been something of a feather in the cap for Washington state.

In 2019, Washington became the first state in the nation to enact a long-term care insurance program, known as the Long-Term Services and Supports Trust Program.

Championed by Democrats, and even a few Republicans, and signed into law by Gov. Jay Inslee, the trust program will provide aging or disabled Washingtonians, who’ve paid into the system and met certain thresholds and requirements, with up to $36,500 in assistance to cover the cost of such services as personal care, assisted living and adaptive equipment.

As Washington’s population ages, it’s estimated that seventy percent of those over age 65 will need some sort of support services, according to the Department of Social and Health Services.

Initial funding for the state program will come from an employee-paid 0.58 percent premium tax on wages – or $290 per $50,000 in earnings – beginning in January 2022 with benefits kicking in three years later. That payroll premium is projected to bring in more than $1 billion a year, but that still won’t be enough to cover all of the anticipated costs of the program over its lifetime.

In order to grow the fund without imposing a higher tax, or reducing the amount of the benefit, the state Legislature this year passed ESJR 8212, a constitutional amendment to allow long-term care trust fund dollars to be invested in stocks and other equities – something that is normally prohibited by the state constitution.

The measure passed the Legislature with near unanimous support. But voters, perhaps unsure of what was at stake, said “no” to the idea in November even though other funds – like public pension and retirement funds – are allowed to be invested in private markets.

Now, having been dealt a defeat at the ballot, the ball is back in the court of state lawmakers to figure out how to make the new program whole.

Republican Sen. John Braun, who sponsored the constitutional amendment, warned there are no easy fixes. In an interview, he said it’s time to rethink the entire program and anticipated a backlash from taxpayers.

“They’re not going to be happy about the payroll tax in January 2022 and even less happy when they find out that payroll tax doesn’t cover the whole bill,” said Braun who voted against creating the program in 2019.

But Democrats control both chambers of the Legislature and are unlikely to back down from their commitment to this new form of social insurance. In a statement, Democratic state Rep. Nicole Macri, who serves on the state’s Long-Term Services and Supports Trust Commission (LTSS Commission), reiterated her support for the program.

“This new long term care benefit will significantly increase security for Washingtonians, given that most of us or someone in our families will have a need for long term care services at some point in our lives,” Macri said.

She added that, “While the solvency risks are real, they will occur several decades from now, so there is time to address them.”

Smith, the state actuary, confirmed that modeling by the consulting firm Milliman shows the trust fund will remain solvent over the next 50 years. The problem begins to appear after that. But Smith said lawmakers shouldn’t delay finding a fix to ensure the program is self-sustaining over the long haul.

“It’s important, but not urgent is how I would describe it,” Smith said. “The longer we wait, however, the less options we’ll have and the less effective those options will be.”

Smith analogized the situation to the federal Social Security program which faces insolvency in 2037.

He noted Washington lawmakers have available two obvious levers to address the shortfall: increase the payroll premium or reduce the amount of the benefit. But neither of those options is likely to appeal to backers of the program.

A third option is to try again to get voters to approve a constitutional amendment to allow for the funds to be invested in private markets. That’s what Democratic State Sen. Karen Keiser, who also sits on the LTSS Commission, would like to do.

“I think definitely we should put another option for the voters to consider,” Keiser said. “I think it really got overwhelmed in all of the incredible politics of 2020, the incredible anxiety of 2020.”

On Thursday, the LTSS Commission agreed with Keiser. It voted unanimously to urge lawmakers to immediately repass the constitutional amendment and send it to voters again in 2021 — signaling a sense of urgency about the matter.

Much of the discussion prior to the vote centered on the belief — that appeared to be supported by post-election polling — that voters likely rejected the measure because they didn’t understand it, or were skittish about the stock market as a result of the pandemic. The consensus was that voters would likely say “yes” the next time around if the explanation in the voters’ pamphlet is improved and it’s made clear that the State Investment Board will manage the investments.

Another advantage, the commission members noted, is 2021 is an off-year election when the ballot won’t be so crowded and turnout will be lower.

“It definitely stands a much better chance in my opinion next year,” said Democratic state Rep. Frank Chopp.

“This next election cycle would be great timing for us,” agreed Republican state Rep. Paul Harris.

Already, advocates of the long-term insurance program are vowing a more robust campaign in support of the measure.

In a joint letter, Service Employees International Union 775, the Washington Health Care Association and AARP Washington State said they would come back “with a larger and stronger campaign” next time.

“Despite the loss at the ballot, we remain optimistic about support for the Trust Act,” the letter said. “This loss is a reflection of the current economic and political realities we face as a state and a country, and not a rejection of the underlying policy or funding strategy.”

This story has been updated.

Related Stories:

The Curious Case Of A Big Company (Boeing) That Wants To Give Up A Tax Break

The Boeing Company is bringing an unusual request to state lawmakers in Olympia: please take away our airplane manufacturing tax break. The Washington Legislature seems likely to oblige, but possibly will add some strings to the deal.

Jay Inslee On ‘Fox and Friends’ Announces Tax Return Release, Calls On President To Do The Same

Washington’s Gov. Jay Inslee is releasing 12 years of his tax returns and calling on President Donald Trump to do the same. Inslee, who’s running for president, made his announcement Friday morning on the TV show ‘Fox and Friends’ on the Fox News Network.

Washington Ranks As The Worst State For Low-Income Residents. Why?

Washington ranks as the worst state for low-income earners to live, and it’s notably worse than others. The Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) places Washington, Texas and Florida at the top of the “terrible 10” list in its annual report.