Washington Launches Statewide COVID-19 Exposure App For Phones. But You Need To Turn It On

READ ON

Washington state on Monday launched a coronavirus exposure alert tool for smartphone users statewide. Washington joined more than a dozen other states further east using an automated, anonymous notification system to aid in the fight against virus spread. Oregon and California are expected to roll out similar smartphone-enabled exposure alerts statewide soon, too.

The smartphone app sends you an alert if you’ve had close contact with another user who later tests positive for the coronavirus. The Washington State Department of Health and governor are hoping that at least 15 percent of Washingtonians voluntarily activate the COVID-19 exposure notification tool. Gov. Jay Inslee said even a low level of participation could reduce infections and save lives.

ALSO SEE: Coronavirus News, Updates, Resources From NWPB

“It’s your choice whether to enable it or download it on your phone,” Inslee said during a press briefing. “But obviously, the more people who take advantage of this, the more who will know they have potentially been exposed to COVID-19.”

In the 15 states that have previously launched the notification technology, adoption has been uneven. More than 1 million Coloradans and more than 1 million New Yorkers have opted in to their state’s new notification systems. While in Virginia, the first state to go live, only about 10 percent of the population has opted in over the course of nearly four months.

How To Set Up Alerts:

Washingtonians who want to receive exposure alerts should look for “Exposure Notifications” under Settings on an iPhone. Android phone users need to first download the “WA Notify” app from the Google Play store. You can opt out at any time.

The wide range of reactions on Twitter to a post by Inslee promoting the app suggested lack of trust in government and privacy concerns could hinder widespread adoption.

“Thanks, just no,” “Absolutely not,” and “Ha ha, not a chance,” replied various Twitter followers to Inslee’s post. Some questioned whether a proprietary app could really offer total privacy. And others voiced suspicion about data collection based on the involvement of Apple and Google in rolling out the technology.

Google and Apple jointly created the underpinnings of the exposure notification system, which individual states are now customizing for their residents.

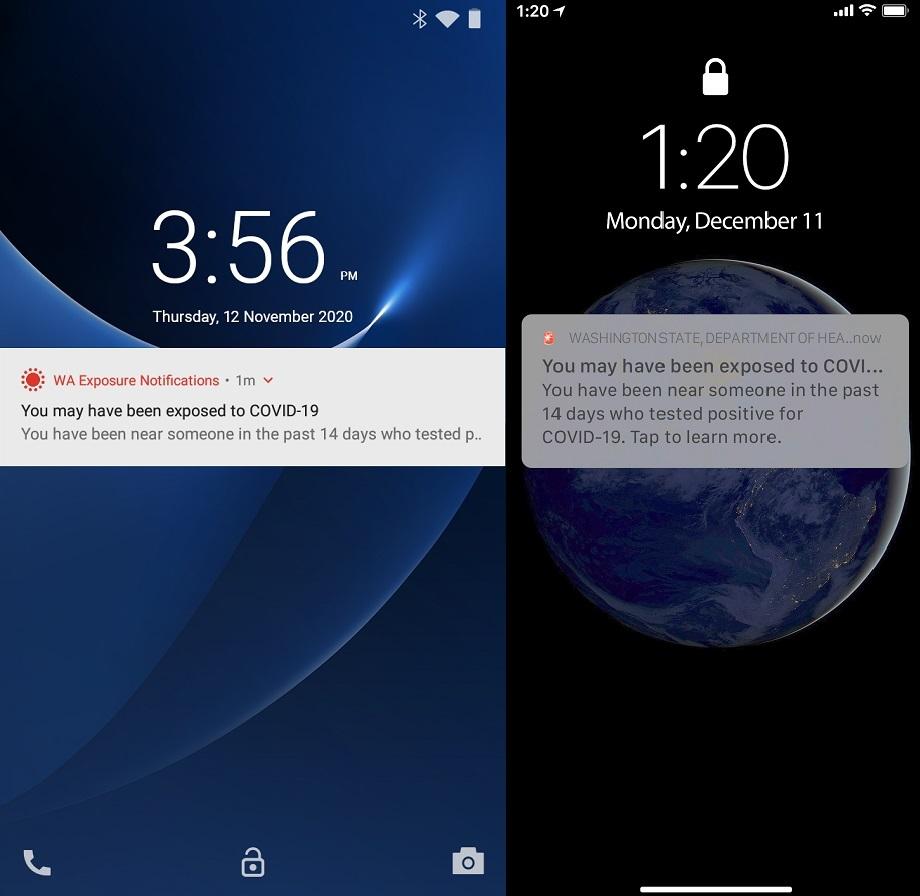

Screenshots of how COVID-19 exposure alerts will look on an Android phone, left, and on iPhone, right. CREDIT: WA Dept. of Health

Inslee said the “elegance” of the notification app is that it maintains privacy while potentially saving lives.

“This is anonymous,” Inslee said repeatedly. “It does not involve location tracking.”

“You won’t be told where this proximity occurred,” he added later.

University students and staff gave the Oregon and Washington versions of the notification app a trial run during November under the oversight of state health authorities. More than 6,500 members of the Oregon State University community enrolled in the first few weeks the app was available for beta testing. A University of Washington pilot project attracted more than 3,500 users before the app launched statewide this week.

An Oregon Health Authority spokesperson reiterated Monday that the university pilot project results would inform the “next steps” toward a wider rollout in Oregon.

Here’s how the free app works when you enable it on your smartphone. The phones of participating users monitor when other users linger close by — using Bluetooth functionality. Your phone stores a rolling 14-day log of people you have been around, but anonymized, so it doesn’t actually store real names. If a person you lingered near later tests positive for the virus, the app sends a confidential note to you of a possible exposure. You are then advised to seek a follow-up COVID-19 test and to self-quarantine.

Washington Secretary of Health John Wiesman said the alert technology supplements traditional contact tracing, but does not replace it.

“We see it as a nice complement to the traditional work that we are doing in case and contact investigations and another tool to help us do our work,” Wiesman said on Monday .

In an interview, UW epidemiology professor and associate dean of the School of Public Health Janet Baseman explained the smartphone app offers several advantages, including faster notice to users that they had a potential exposure to a known COVID-19 case. In addition, it can cover gaps in contact tracing stemming from when an infected person can’t remember or is reluctant to share the names of all the people they hung out with while infectious.

ALSO SEE: Coronavirus News, Updates, Resources From NWPB

“The other interesting thing that this technology can do for us is have exposure notification messages go out to people who never would have been identified as a close contact through traditional contact tracing,” Baseman said, thinking of users who lingered around other people they don’t know personally.

The enlistment of regular people’s smartphones in the fight to control the spread of the virus comes amid a surge of COVID-19 cases. During November, Washington state and Oregon repeatedly set new records for the number of daily COVID-19 infections. As of Monday, nearly 2,800 Washingtonians had died from COVID-19.

The smartphone app follows guidance from the federal Centers for Disease Control in its definition of who would be at risk of exposure. Notifications go out to people who came within six feet of a person who later tested positive and who had a long close contact (15-30 minutes) or repeated short close contacts on the same day with that person.

Related Stories:

Contract Tracing Efforts Are Buckling Under The Heavy Northwest Coronavirus Caseload

Since early in the pandemic, rapid contact tracing has been considered one of the keys to controlling the spread of the coronavirus. But in recent weeks, an overwhelming surge in new cases has let thousands of COVID-positive people and their close contacts fall through the cracks.

Conspiracy Theories Aside, Here’s What Contact Tracers Really Do To Help End The Pandemic

Misinformation and conspiracy theories abound, from tales that people who talk to contact tracers will be sent to nonexistent “FEMA camps” — a rumor so prevalent that health officials in Washington state had to put out a statement in May debunking it — to elaborate theories that the efforts are somehow part of a plot by global elites.

3 Things The U.S. Can Do Right Now To Slow Coronavirus Spread

Seven months since cases of the coronavirus were first reported, some countries have effectively combatted the virus and brought the spread under control. The United States is not one of them. But experts say it’s not too late.