States Are Preparing To Distribute A Coming COVID Vaccine. Here’s How Washington Is Preparing

BY HANNAH WEINBERGER / CROSSCUT

That medical experts have warned of a winter surge of the coronavirus since the early days of the now year-old pandemic doesn’t make the lived reality of it any less sobering. Cases are surging in almost every state, and exponential growth promises a long and deadly season, adding to the 1.4 million lives globally claimed so far by the pandemic, including more than 259,000 in the U.S. and more than 2,655 in Washington state. But just as the predicted darkness descended on the country, hope for an end to the pandemic also arrived.

In the past week, two separate trials for COVID-19 vaccines have claimed to significantly beat expectations for vaccine effectiveness, with a third showing promising results. Both Pfizer and Moderna say they have each reached about 95% effectiveness in Phase 3 trials of their respective vaccines, which means that only 5% of the COVID-19 cases identified in their trial participants were found in those who had been given vaccines.

“This is mind blowing,” says Dr. Jeff Duchin, Public Health — Seattle & King County’s health officer. “Nobody expected a COVID vaccine to be 95% effective. Our very best vaccine is the measles vaccine and it’s about 95% effective.” While the companies’ data have not been made publicly available, Duchin says he thinks their estimates are probably right. They would “basically be shooting themselves in the foot by announcing something that’s not true and then have it be widely discredited a few weeks later, ” he says.

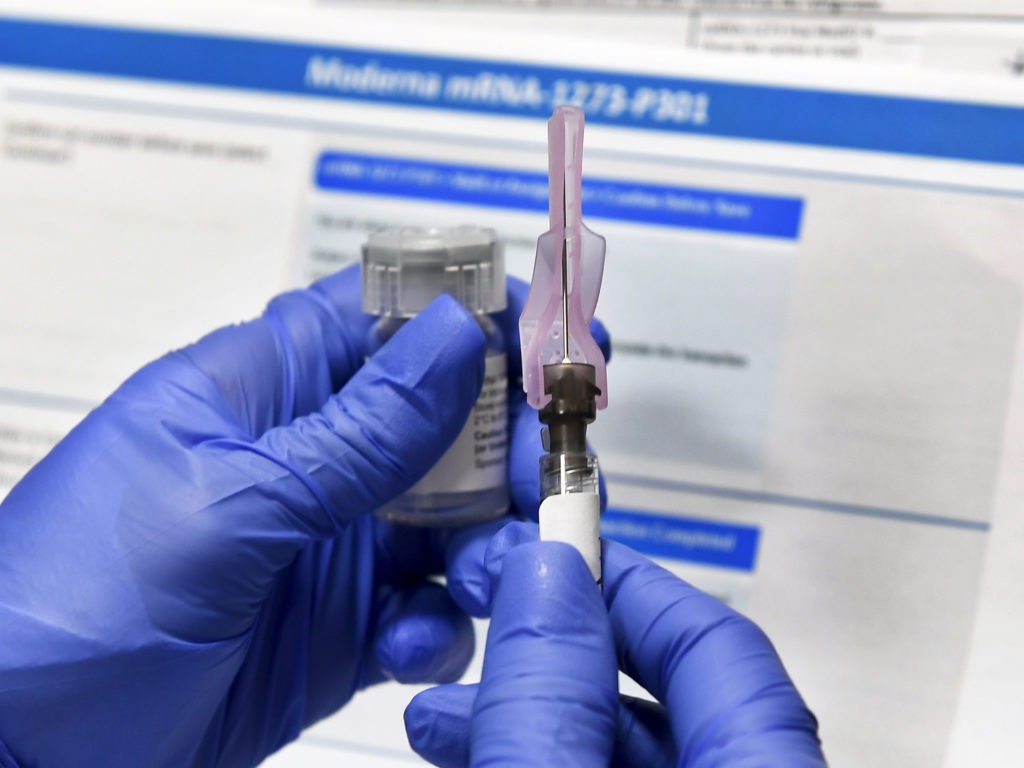

With development and testing underway, health officials are asking states to prepare for limited distribution of a potential vaccine as soon as mid-December. CREDIT: Hans Pennink/AP

Officials report that a vaccine could possibly be administered to some high-risk individuals before the end of the year, but people everywhere are curious about when and how the vaccine will be made available to all and what the timeline might be for life returning to some semblance of normalcy.

There has been a good deal of reporting on the science of vaccine development and manufacturing and the regulatory process around it, but what will most impact the trajectory of the pandemic is how ready our state and local governments are to distribute and administer vaccines. It’s a tough job to plan for, given the number of unknowns. Yet, many states, including Washington, have made first stabs at that process through lengthy draft plans.

Washington’s plan, devised by the state Department of Health, will be implemented by a 25-person Vaccine Planning and Coordination Team consisting of employees from within the department, sourcing from the Offices of Immunization and Child Profile, Emergency Preparedness and Response, Health Promotion and Education and others.

The current 71-page plan is a draft, which means that it will likely change. While spreading the word of the plan throughout the state, the team behind it is also seeking feedback — especially from marginalized communities at the highest risk in the pandemic and that have historically been underserved — or worse — by the medical system.

It does, though, provide an outline for a possible rollout. Here, we answer — as best as anyone can — what that rollout might look like.

Will the vaccine be safe when it’s available?

An advisory panel of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration will be meeting to discuss emergency use authorization for the Pfizer vaccine on Dec. 10. Distribution of the vaccine to states could happen within 24 hours of that meeting, with vaccines available as early as Dec. 12. That’s fast and has added to concerns about the safety of a vaccine.

Yet, approval by the FDA, which is required for distribution, is a gold standard for a vaccine, says Dr. Paul Offit, director of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia’s Vaccine Education Center, and a member of that FDA advisory panel.

“I think if we get to this point in this country where you don’t trust the FDA, we’re in trouble,” he says.

Coronavirus vaccines, like every other vaccine before them, go through multiple levels of safety testing. However, because the drugmakers are applying for emergency use authorization, the timeline for these assessments is shorter. As a result, some skeptics are concerned the drugmakers and the FDA won’t understand the extent of serious side effects.

Yet two centuries of experience with vaccines have shown that serious side effects tend to turn up within months. “I think the two-month safety net at least tells you that you don’t have a serious adverse event that is relatively uncommon,” Offit says.

The government will continue assessing the effectiveness and risk of the vaccines through ongoing monitoring programs.

Also, some states — including Washington — have joined forces or individually vowed to launch their own state-based safety assessment programs over concerns that the Trump administration has mishandled its role in vaccine development. It is unclear whether those programs could delay the distribution of a vaccine.

Will everyone in Washington be able to get the vaccine immediately?

No. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention anticipates very limited availability of vaccines in the beginning. Pfizer, for instance, thinks it can produce 50 million doses by year’s end for the world’s population. As a result, vaccinations will be focused on people deemed most in need of them, according to state vaccination plans.

“It’s going to be the Beanie Baby phenomenon,” said Offit. “I mean, this is a limited edition vaccine.”

The state of Washington estimates it will receive 2% of all vaccine doses during the first two months of their availability, when they are scarcest, and suggests it could vaccinate between 150,000 and 400,000 people in that timeframe.

To determine who gets vaccines and when, Washington state is following ethical guidance from the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices and the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine. According to Duchin, the plan will be executed “in an orderly way, based on a framework that incorporates [people’s] risk of disease and ethics and transparency, and who’s getting offered a vaccine at what time.”

File photo. An adult gets a flu shot in Jacksonville, Fla. CREDIT: Rick Wilson/AP

Groups being considered for Phase 1 vaccination include, in descending order of priority, 500,000 health care workers; 53,000 high-risk first responders, including emergency medical technicians and firefighters; more than 3 million people of all ages with co-morbidities; 33,000 older adults in care facilities; and an undetermined number of essential workers. The CDC’s advisory committee’s new draft guidance prioritizes residents of long-term care facilities at the same level as health care workers.

The state notes that Phase 1 distribution could also take into consideration equity factors, such as whether people live in areas with high COVID-19 risk or are from vulnerable groups.

The second phase will kick in when there’s enough vaccine to immunize more people and the capacity to store those doses. When that will happen is still unclear. The National Academies’ suggestions for people in the second phase of vaccine eligibility include essential workers in high-risk situations, teachers, people in detention facilities, people with slightly less severe co-morbidities, the unhoused and all other older adults. It is likely that people in Phase 2 could be vaccinated even if Phase 1 is not yet complete.

What’s this about storage?

Storage is a significantly limiting factor for vaccine distribution, and a real concern. One issue with the two leading vaccine candidates is that both require cold storage to keep — with Pfizer’s requiring unprecedentedly cold conditions. Depending on which vaccines become available, some states and counties might not have access to all the necessary cold storage.

Washington state has three possible scenarios in place for cold storage, depending on vaccine requirements: ultracold, frozen and a mixture of both. The state Department of Health doesn’t currently have this kind of storage capacity, and the CDC has not asked the state to look for that ultracold storage just yet. But it is trying to gauge what storage options might be available in the state, and how much dry ice it will need to keep vaccines cold in transit. It estimates that for the first two months that a vaccine is available, the state will need between 7,000 and 20,000 pounds of dry ice.

“Vaccine capacity will be directly impacted by freezer capacity in the state,” the state plan says. “We are working with local health jurisdictions and health care partners to document and map storage solutions, redistribution costs, and cold-chain management.”

“I believe we’ll have enough of those freezers in King County to allow us to distribute that particular [Pfizer] vaccine product,” Duchin said Friday, “but in some communities across the country, that will be a real challenge.”

What will getting a vaccine in Washington look like?

There are 17 standard vaccinations given to people in the U.S. over their lifetime, so barring parental or personal decisions or immunocompromisation, you’ve had one. The mRNA-based COVID vaccines might work differently than previous vaccines approved for human use, but in terms of how you’ll experience it — a shot in the arm — it is likely to be a familiar process.

Only people licensed to administer vaccines will be allowed to do so.

However, there are things no one is sure of just yet: How many shots you’ll have to get — it depends which vaccines get approved — and how long immunity from each vaccine will last, which we won’t fully understand without long-term monitoring.

Also, choosing which one to get might be difficult. Depending on your medical provider, you may have access to some vaccines and not others.

So who’s actually giving vaccines to people in Washington?

The state Department of Health’s Office of Immunization and Child Profile is working with health care providers that can serve priority populations to sign up groups that can administer the vaccine initially.

“I haven’t seen or heard any recent numbers for King County,” Duchin said Friday of how many health care providers in the county are signed up to administer vaccines yet. “I know this is in process currently, so it’s not finished. We don’t know the final number at this point. But the state has been reaching out to hospitals and health care systems to get them signed up.”

The state has been doing outreach to health care providers and pharmacies that might be able to support vaccination later in the process as well. “We have gauged that nearly 90% of pharmacies across the state are interested in enrolling to provide COVID-19 vaccine,” the authors of the state’s draft plan write. “There are about 1,000 pharmacies in Washington (not including hospitals) and about 9,000 licensed and practicing pharmacists.”

Additionally, the federal government has developed partnerships with 60% of chain pharmacies nationwide for distributing the vaccine.

How much is this going to cost me?

It’s not completely clear. Estimates have the vaccine costing less than $100, but it’s not apparent who will actually pay for that, especially without knowing how much of the total vaccination tab hospitals, health departments and other groups will have to pick up.

While Operation Warp Speed — the federal plan to fund and promote vaccine development — has an approximate budget of $10 billion, planning for vaccine distribution hasn’t received the same funding treatment. The CDC so far has distributed only $200 million to local jurisdictions for vaccine preparedness, when between $6 billion and $8 billion is expected to be necessary, according to a Kaiser Family Foundation analysis. The state Department of Health says it has received $5 million.

“The vaccine was developed [with] Operation Warp Speed, and the public health capacity to deliver this vaccine is proceeding at Operation Status Quo,” Duchin says. ”We are really, really hurting with the ability to do the type of advanced planning that we would like to do, if we had resources that should be made available to prepare for [an operation] larger than anything else we’ve ever done in public health or in emergency response in this country.”

So let’s assume I get the vaccine. Does that mean I can pass go and collect $200? Is this whole nightmare done now?

These vaccines will not be panaceas. There’s still uncertainty about how long they might be effective, given that the vaccines being tested will have only a few months of safety data behind them.

“A fear [is], are we going to have a vaccine that is effective for much shorter than we thought? Which would be a problem,” Offit says. “Now, I don’t think that’s going to be a problem. But you don’t know.… I think if it is effective for two months, it’s likely to be effective for longer.”

There’s also concern about whether the vaccines will be effective at preventing severe cases of COVID-19. Moderna’s Phase 3 trial, though, showed that none of the most severe cases of COVID happened in the test group that had received Moderna’s vaccine.

But if we get to a point where we have a vaccine, even then it’s just one tool in our pandemic toolbelt. Vaccines don’t immediately create herd immunity, and we’ll still need to maintain good hygiene — especially if vaccines protect against illness, but not asymptomatic infection.

“Can we discern the amount of infectious virus that’s being secreted and then make a statement about whether or not we think that person would be contagious? The reason that’s relevant, obviously, is … you may still be dangerous to others,” Offit says, giving a hypothetical situation in which a vaccine that’s 95% effective at preventing illness might be only 15% effective at preventing asymptomatic infection. “If you care about others, you should still want to wear a mask and social distance because until we get this virus under control,” he says. “That would still be a problem.”

“But,” he adds, “I think you should be incredibly optimistic that we now have in hand, in all likelihood, a way out of this mess.”

Duchin, King County’s health officer, has been similarly excited by this news. “There’s light at the end of the tunnel. But first we need to get through the next few months.”

Originally published Oct. 20, 2020 on Crosscut.com. Visit crosscut.com/donate to support nonprofit, freely distributed, local journalism.