Internal Documents Reveal COVID-19 Hospitalization Data The Government Keeps Hidden

LISTEN

BY PIEN HUANG & SELENA SIMMONS-DUFFIN

As coronavirus cases rise swiftly around the country, surpassing both the spring and summer surges, health officials brace for a coming wave of hospitalizations and deaths. Knowing which hospitals in which communities are reaching capacity could be key to an effective response to the growing crisis. That information is gathered by the federal government — but not shared openly with the public.

NPR has obtained documents that give a snapshot of data the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services collects and analyzes daily. The documents — reports sent to agency staffers — highlight trends in hospitalizations and pinpoint cities nearing full hospital capacity and facilities under stress. They paint a granular picture of the strain on hospitals across the country that could help local citizens decide when to take extra precautions against COVID-19.

Withholding this information from the public and the research community is a missed opportunity to help prevent outbreaks and even save lives, say public health and data experts who reviewed the documents for NPR.

The ICU at Tampa General Hospital in Tampa, Fla., was 99% full this week, according to an internal report produced by the federal government. It’s among numerous hospitals the report highlighted with ICUs filled to over 90% capacity.

CREDIT: Michael S. Williamson/The Washington Post via Getty Images

“At this point, I think it’s reckless. It’s endangering people,” says Ryan Panchadsaram, co-founder of the website COVID Exit Strategy and a former data official in the Obama administration. “We’re now in the third wave, and I think our only way out is really open, transparent and actionable information.”

The documents show that detailed information hospitals report to HHS every day is reviewed and analyzed — but circulation seems to be limited to a few dozen government staffers from HHS and its agencies, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Institutes of Health, according to distribution lists reviewed by NPR. Only one member of the White House Coronavirus Task Force, Adm. Brett Giroir, appears to receive the documents directly.

“Our goal is to be as transparent as possible, while still protecting privacy,” an HHS spokesperson wrote in an email to NPR. “HHS and the White House Coronavirus Task Force utilize hospital capacity data to gain greater insights into how COVID-19 is spreading and impacting the population, and to better inform response efforts like staff deployments and supply shipments.”

What data is being collected and shared internally?

The daily reports show county, city and hospital-level details, as well as national analyses that HHS does not post online.

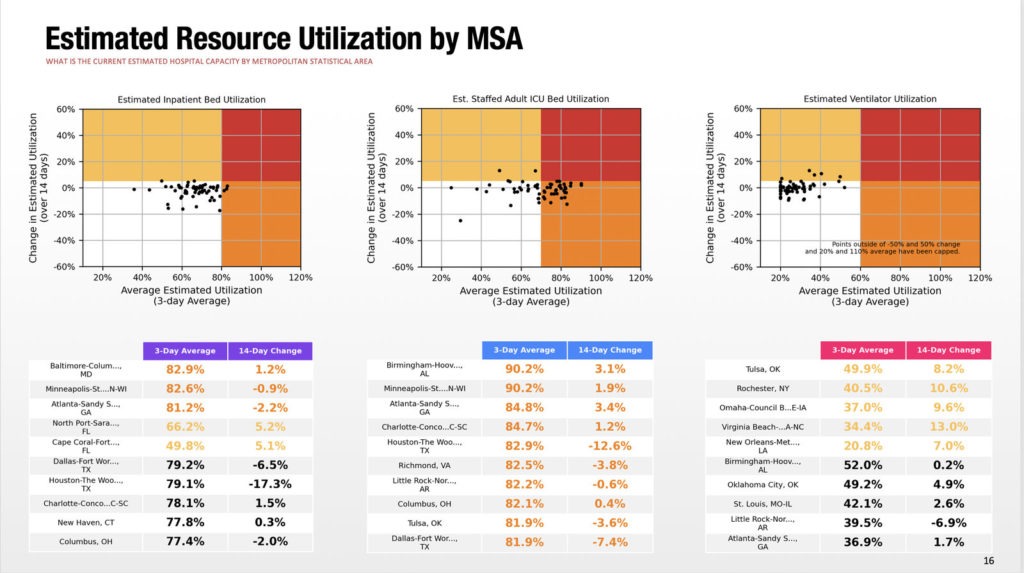

For instance, the most recent report obtained by NPR, dated Oct 27, lists cities where hospitals are filling up, including the metro areas of Atlanta, Minneapolis and Baltimore, where in-patient hospital beds are over 80% full. It also lists specific hospitals reaching max capacity, including facilities in Tampa, Birmingham and New York that are at over 95% ICU capacity and at risk of running out of intensive care beds.

In reviewing the analysis obtained by NPR, Panchadsaram says the local and hospital-level data HHS is collecting would be very useful to researchers and health leaders. “That stuff isn’t easy to find at a national level,” he says. “There’s no one place [publicly] you can go to get all that data.”

Hospitalization data is invaluable in looking ahead to see where and when outbreaks are getting worse, says Dr. Christopher Murray, director of the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington. “Right now, as we head into the fall and winter surge,” Murray says, “we’re trying to put more emphasis on predicting where systems will be overwhelmed.”

But what’s missing for this kind of planning, he says, is “exactly the information” that appears in the internal report.

NPR has reviewed several of these reports generated in the past month. They present trends in hospital use, including increases in ventilator usage, along with a growing number of inpatient and ICU beds being occupied by COVID-19 patients. The Oct. 27 report showed that all three measures have increased by 14%-16% in the past month.

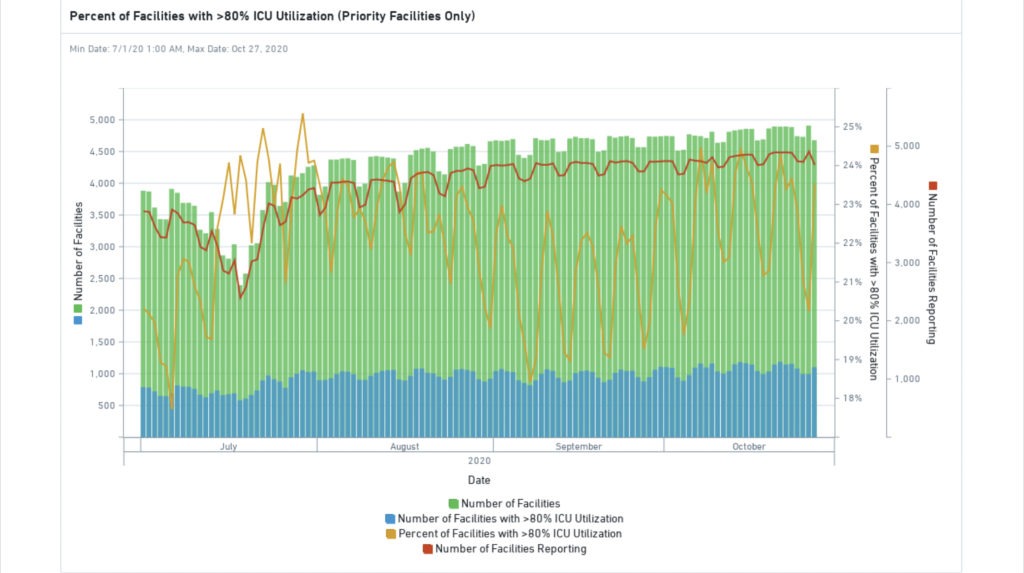

About 24% of U.S. hospitals are using more than 80% of their ICU capacity, based on reporting from nearly 5,000 “priority facilities,” and more hospitals have joined their ranks in recent weeks.

A page from a report shared internally to HHS staffers presents hospital data from Oct. 27, including a list of cities where hospital and ICU beds are filling up. SOURCE: HHS

Researchers say observing these trend lines can help the nation know how to prepare for surge and be ready to intervene before systems become overwhelmed.

Daily hospitalization numbers in particular are key measures for tracking pandemic hotspots, Murray says, because they reflect the number of severe COVID-19 cases in a community.

“The best possible measure of where we are in the pandemic, and the one we would want to anchor modeling to, is daily hospitalizations,” he says, which give an early warning of deaths that will likely follow.

Panchadsaram’s data-tracking site COVID Exit Strategy pulls state-level hospital capacity estimates from HHS when they’re updated, which generally happens once a week. In reviewing the reports obtained by NPR, Panchadsaram says it’s clear that vital data is flowing into HHS daily. “But sharing with the public seems to be an afterthought,” he says.

Gaps in transparency for state and local leaders

HHS tells NPR that more than 800 state-level employees have access to the daily hospitalization data it gathers, but only for their own state, unless another state grants them permission to view its data.

Without a larger view into national or regional data, some states — like Tennessee, which has eight bordering states — are missing out on valuable regional data, says Melissa McPheeters, who directs the Center for Improving the Public’s Health through Informatics at Vanderbilt University.

“Hospitals in Tennessee serve patients who are from Arkansas and Mississippi and Kentucky and Georgia and vice versa, and so we’re a little bit blind to what’s going on there,” she says. “When we see hospitals that are particularly near those state borders having increases, one of the things we can’t tell is: Is that because hospitals in an adjacent state are full? What’s going on there? And that could be a really important piece of the picture.”

A page from a report shared internally to HHS staffers shows the rising percentage of hospital ICUs that are at or above 80% capacity. It reflects data as of Oct. 27. SOURCE: HHS

Lisa M. Lee, former chief science officer for public health surveillance at the CDC, now at Virginia Tech, says the federal government could help states work together across borders.

“It’s very challenging for states to get the multistate view of things,” she says. “It’s just a lot easier when there’s a knowledgeable third-party who can pull the data together, make them consistent across states and actually tell the story of what the information shows.” Typically, she says, this role would be fulfilled by the CDC, but the agency was stripped of its role in collecting COVID-19 hospital data in July.

This kind of visibility into data could help policymakers decide how best to curb the spread of the virus. McPheeters and colleagues at Vanderbilt put out a report this week that found that Tennessee counties without mask mandates had more rapid increases in hospitalizations. That kind of analysis and insight would be possible at a much larger scale if HHS shared more granular hospitalization data, she says.

It could influence behavior among the public, says Lee. “The neighborhood data, the county data and metro-area data can be really helpful for people to say, ‘Whoa, they’re not kidding, this is right here,'” she says. “It can help public health prevention folks get their messages across and get people to change their behavior.”

A controversial data switch

Experts who reviewed the internal documents for NPR say that even for the limited group of federal employees who get them, the daily reports are not as useful as they could be.

“We’re so focused on counting things but not contextualizing them,” explains McPheeters. A community hospital might become overwhelmed at a different point than a big academic hospital, and without that context, she says, it’s impossible to tell: “Is 75% [full] a good thing or is 75% a bad thing?”

Health data experts NPR consulted had ideas on how to improve the analysis. For instance, Panchadsaram suggested that some of the county-level charts, currently presented as raw numbers, would be more useful if analyzed per capita. “You really need to adjust it to the number of people [in an area] to get a sense of where things are being overwhelmed,” he says.

And the quality of the underlying data is a concern. Health experts say the data quality was compromised by a controversial shift in data collection from the CDC to HHS in July, and that the issues with data quality have not been fully resolved.

Hospitals have had to adjust to onerous new reporting requirements, and the hospital data is no longer checked and analyzed by seasoned epidemiologists and other experts at CDC.

The daily trend documents circulated at HHS include this disclaimer: “This analysis depends on the data reported by hospitals. To the extent that the data is missing or inaccurate, this analysis will also reflect those issues.”

According to HHS data posted on Monday, just 62% of the nation’s hospitals reported all the required information last week.

But greater transparency, even of incomplete data, can be invaluable in a crisis, experts say.

HHS told NPR that since it took over collecting hospital capacity data, it has “consistently displayed state-level hospitalization data to help inform the public about COVID-19 prevalence in their communities.”

But public health experts say the state level data isn’t detailed enough — and since the government is putting the effort into generating more granular daily analyses, it should share them.

“Even though they’re collecting all these things and putting so much effort behind it, it gets blocked when it tries to get out of the door,” Panchadsaram says.