Why An Irrigation District Wants To Flood A Kennewick Family’s Pumpkin Farm

Listen

Dusty pumpkins slap between rough hands as workers throw them into a tractor’s trailer.

It’s a rhythmic, full sound, like a child testing a drum.

This third-generation farm supplies more than 600,000 pumpkins to Walmarts, Wincos, Yokes and Home Depots in Washington, Oregon, Idaho and Alaska. But here in southeast Washington near the Tri-Cities, the farm’s future is at stake.

There’s a fight over a proposed reservoir that pits these third-generation pumpkin farmers against thousands of potential water users.

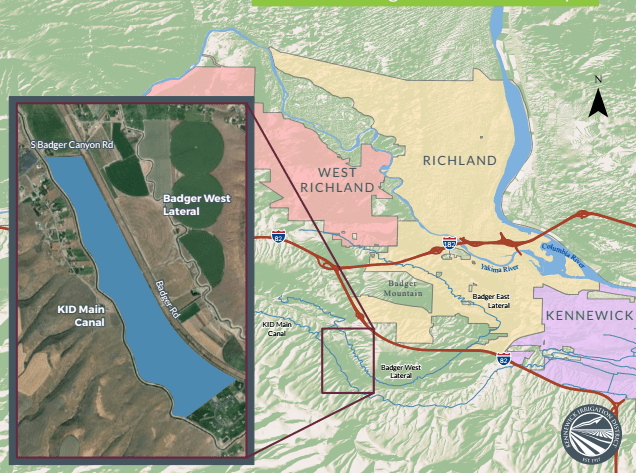

The Kennewick Irrigation District, or KID, wants to flood 400 acres of land for a new reservoir. It’d take at least eight to 10 years to design, permit and build. A project on this scale hasn’t been built in the Yakima Basin since the 1930’s. And this 65-acre pumpkin farm is in the way.

‘Premium dirt’

“Well, you can get angry,” Robert Cox says. “But I think I’m more sad.”

Cox’s snap shirt and jeans are coated with “premium dirt,” quality sandy silt from his fields. Everyone calls him Robbie. It’s his land and hard work, but he loves doing it.

Robert “Robbie” Cox and his daughter Ashley Elliott-Cox stand in a pumpkin field on their farm outside of Kennewick, Washington. Robert says he enjoys the feeling of growing pumpkins for kids to carve. CREDIT: Anna King/N3

“I don’t know what I like about it, ‘cause, my back hurts,” Cox says with a wry smile. But farming so children can make happy jack o’lanterns also, “makes you feel good,” he says.

The proposed reservoir would hold 12,000-acre feet of water. (An acre foot of water is the volume of one acre of surface area to a depth of one foot. One acre foot is about 326,000 gallons.) It’s not for drinking, but for irrigation in drought years to 600 hundred farmers and thousands of urban lawns.

So far, the district has offered almost $2 million for the Cox farm, more than twice the farm’s recent assessed value of $774,535.

But the Cox family doesn’t want to sell.

“Our farms shouldn’t be pushed out of the way to make sure the people in town can have a nice lawn,” Cox says.

A rendering of the proposed “central storage” reservoir near Kennewick, Washington. Courtesy of Kennewick Irrigation District

Future needs

Charles Freeman manages the Kennewick Irrigation District.

“We’re concerned with the family farm,” Freeman says. “That’s why we’re working with them until everything stopped and they chose this path.”

Freeman says the district is facing urban growth but diminishing water from the Yakima River. Upstream irrigation districts are getting more efficient at conserving water.

“We have great projects (such as) canal lining,” he says. “We believe in that. We support that. But KID has to plan for the future and this reservoir, it’s central to our future.”

Freeman says it’s crucial to build a reservoir before there are no unbuilt parcels left.

Farmer Robbie Cox acknowledges KID could legally take the land.

“They’re a government entity,” Cox says. “They can do eminent domain if it’s for the public’s best interest. So far, we’ve had a lot of public input, and nobody’s interested in this reservoir being located here.”

“We’re sensitive to that,” Freeman says, noting the district hasn’t taken private property for 10 years. “We’re sensitive to condemning property. I mean, nobody wants to do that.”

But he thinks there’s a silent majority in favor of the reservoir.

“KID’s rate base is approximately 66,000 people [25,000 payment accounts],” Freeman says. “We have not heard from them.”

Cox argues those 66,000 people in growing cities will need farmland in the future more than green lawns.

“This little coronavirus scare might have jolted some brains of people in town and throughout the world, that we still need to eat,” Cox says.

The irrigation district won’t decide the farm’s fate until after an engineering study is done next spring.

But for now, the Cox family has posted big red signs along the road reading: “Save The Farm.”

Related Stories:

Snake River water, recreation studies look at the river’s future

People listen to an introductory presentation on the water supply study findings at an open house-style meeting in Pasco. After they listened to the presentation, they could look at posters

Tri-Cities forum draws support for Lower Snake River dams

At a Lower Snake River dams forum in the Tri-Cities, Chuck Bender, who said his family members are tugboat operators, fell to his knees in front of U.S. Rep. Dan

As the Northwest turns toward Spring, agricultural irrigators, fire managers and water experts watch the sky

Workers clear canals of debris in preparation for spring irrigation season in the Roza Irrigation District. (Courtesy: Dave Rollinger) Listen (Runtime 1:00) Read A story in plot points: a federal