PULLMAN, Wash. – Neida Regis began working in Washington orchards when she was 14. Now 20, she knew she and her family had to return to the harvest this year, even under the threat of COVID.

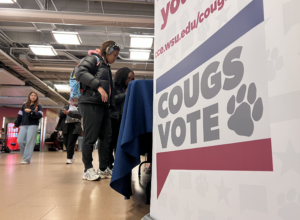

Neida Regis working in the orchards in Washington | PHOTO CREDIT: ALANA LACKNER (MURROW NEWS)

“After multiple people got sick from work, multiple people stopped showing up. A lot of people were getting sick,” said Regis, a pre-nursing student at Washington State University. “It was really scary, but we were okay.”

Now a junior, Regis has been involved with WSU’s College Assistant Migrant Program (CAMP) since she was a freshman. CAMP helps students from seasonal- or migrant-farm-working families adjust to life at WSU and get to know others from similar backgrounds, said Michael Heim, the program’s director.

Heim says he has seen how difficult the pandemic has been for seasonal farmworkers and their families, emotionally and economically.

“Coming from … an economy where when they’re working they get lower income based on the type of work that they’re doing, two weeks is very serious for them,” Heim said. “You come home one day and you realize ‘I have COVID-19 and I’ve been around my family all day’ and suddenly that income is gone.”

After the COVID-19 pandemic started in March, Regis wasn’t sure what to expect from the summer when she returned home to Toppenish., she said. She knew the virus had altered daily life around the globe. Regis and her family spent their summer outside in the heat, completely covered to protect themselves from getting scratched by the trees or infected by the virus.

“My mom had bought us the face shields to wear at work,” Regis said. “But it turned out it was way too hard to use those because there’s so many branches.”

Regis said her mother decided to try something else and bought them a different kind of mask with an elastic headband piece attached to cloth that wrapped around and covered the whole face. Regis said these worked better than the shields, but there were still a lot of challenges.

“It would be super-hot, like 102 degrees,” she said. “We obviously had to be covered … but it was so hard to do that in the heat.”

Regis said everyone in the orchard was very careful to wear a mask and use hand sanitizer, despite the difficult conditions. For them, it wasn’t just an illness — it also meant two weeks without pay while they quarantined.

Heim said he worries about the farm workers because of what contracting COVID-19 could mean for their health, both in the short-term and long-term.

Neida Regis working in the orchards in Washington | PHOTO CREDIT: ALANA LACKNER (MURROW NEWS)

He believes the work they are doing in the midst of a global health crisis deserves respect, especially because Yakima County, where Toppenish is located, experienced high transmission rates over the summer.

“It is astonishing … the level of resilience our migrant and farm-working communities have shown throughout this pandemic,” he said.