$165,000 A Week For COVID Analysis? That’s How Much Washington State Has Paid A Consulting Firm

Listen

NOTE: This story was reported in collaboration with Joe O’Sullivan of The Seattle Times.

In early June, as Gov. Jay Inslee was overseeing a phased reopening of the state, his budget office signed a contract with the elite international consulting firm McKinsey & Company to provide access to a “Governor’s Decision Support Tool.” That tool was meant to aid Inslee’s decision-making as he gradually unlocked the economy.

But access to McKinsey’s customized COVID-19 risk tool didn’t come cheap. Under the contract, the state initially agreed to pay for eight weeks of access to McKinsey’s services and proprietary data sets. The cost to taxpayers: $165,000 per week. And that was McKinsey’s government discount rate.

“We recognize that that’s a lot of money, but this is a strange time and the governor needed that data and needed the information to help him make his decisions,” said Tara Lee, Inslee’s communications director.

ALSO SEE: Coronavirus News, Updates, Resources From NWPB

The June agreement is one of three, six-figure-a-week, no-bid contracts the state of Washington has entered into with McKinsey – one of the largest consulting firms in the world — in the midst of the pandemic, according to a review by the public radio Northwest News Network and The Seattle Times. The nature and price of the contracts has raised questions about whether there were better, more cost effective ways to spend that money.

In May, the state’s embattled Employment Security Department (ESD) contracted with McKinsey for $142,000 a week for eight weeks to help it respond to a massive unemployment insurance fraud scheme. That contract was later extended to keep McKinsey engaged through as late as September at a cost not to exceed $2.4 million.

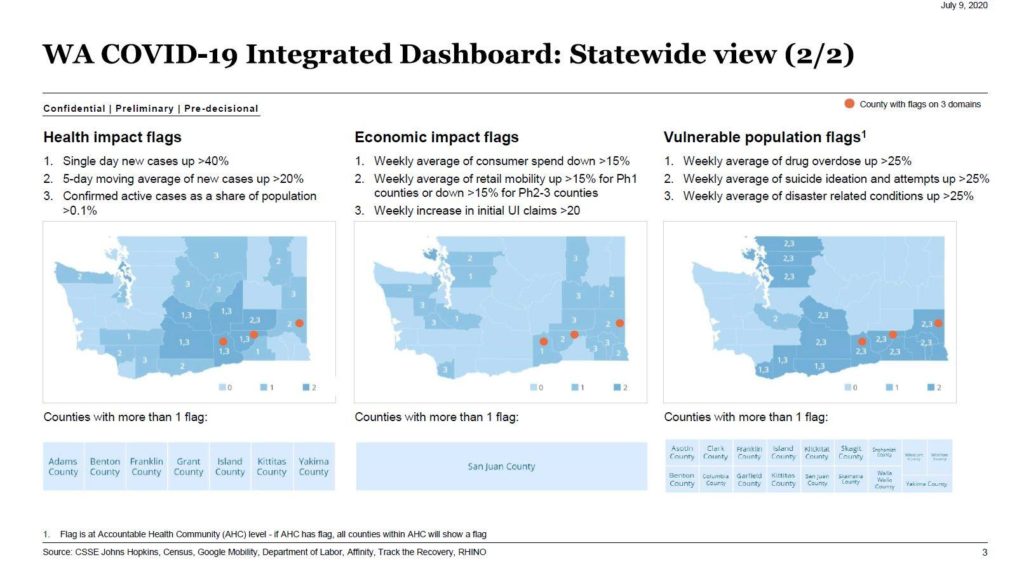

This screenshot shows an example of McKinsey & Company’s “Governor’s Decision Support Tool.” The office of Washington Gov. Jay Inslee contracted for access to this tool and a team of four consultants from McKinsey for $165,000 a week for eight weeks. Courtesy of WA Governor’s Office

In an internal email explaining the reason for the contract extension, ESD Commissioner Suzi LeVine said her agency’s “internal capabilities” to fight off fraud were not ready yet.

“Our hope is that, with this additional time with [McKinsey], we’ll be able to build out the team and upskill some key members of the team so that we can have a sustainable anti-fraud stance in our systems,” LeVine wrote in her email.

Also in May, Washington’s Health Care Authority (HCA), which runs the state’s Medicaid program, inked a $1.2 million short-term contract with McKinsey to help match positive COVID-19 tests with people on the state’s Medicaid rolls, with the goal of faster contact tracing and case management for those individuals. McKinsey’s work, according to HCA, was to perform a “proof of concept” use case as part of a longer-term health and human services master database project.

In all three instances, federal dollars have or will cover the cost of the contracts with McKinsey. In the case of the governor’s office contract, the Office of Financial Management said McKinsey hasn’t yet invoiced the state. When it does, the bill will be paid for using some of the nearly $2 billion in federal CARES Act money the state has received.

The contracts with McKinsey were among more than $61 million in COVID-related “special market conditions” agreements and purchases the state entered into beginning in March, according to a database provided by the Department of Enterprise Services (DES) in response to a public records request. More than half of that spending was by the state Department of Agriculture to purchase and stockpile non-perishable items, like peanut butter and canned tuna, to meet the skyrocketing demand for food from out-of-work individuals and families. There were also direct grants to food banks.

That spending was separate from the hundreds of millions of dollars in orders DES and the Department of Health have placed for personal protective equipment, testing supplies and other health care items related to the COVID-19 response.

In each instance, these “special market conditions” agreements were signed without a competitive bidding process as the state wrestled with the widespread fallout from the global pandemic. Typically, sole source contracts are prohibited by state law. But after Inslee declared a state of emergency in early March, the director of DES temporarily waived the competitive solicitation requirement “for goods and services that are directly related to the state’s response to the coronavirus.”

That made it easier for the Inslee administration to say “yes” to offers for outside help, as well as pursue unique arrangements as it sought to respond to the pandemic. For instance, Inslee’s office also contracted with Raquel “Rocky” Bono, a surgeon and retired Navy vice admiral, to serve as the state’s health care system response coordinator. She is paid $16,000 a week.

“We just were willing to try some things,” said David Postman, Inslee’s chief of staff. “And we’ve been really grateful for the work that’s been done by a variety of people and entities and organizations and think that it’s helped us.”

Some of that work has been donated. For instance, Microsoft helped build two COVID-19 dashboards for the state pro bono. In addition, a nonprofit called Restart.us has provided Washington with a free, open-source “decision tool” designed to help states determine how much personal protective equipment they need.

While McKinsey charged for its services, a spokesperson said the company is “proud” of the work it’s done on behalf of the public sector.

“Like many other companies, we chose to engage and do our part in helping governments fight this pandemic,” the spokesperson said in a statement.

It’s not just Washington that’s contracted with McKinsey in the midst of the pandemic. In July, the nonprofit investigative news site ProPublica reported that the consulting giant has earned more than $100 million advising local, state and federal governments on their pandemic response.

On a web page touting its COVID-19 work in the U.S., McKinsey said it’s assisting state and federal governments with data analysis, building organizational capabilities and helping to assess the economic impacts of the pandemic.

But, the ProPublica investigation concluded that it’s not evident what those governments have “gotten in return.”

“It’s too early to fully judge these engagements, but a preliminary assessment shows mixed results,” wrote reporter Ian MacDougall.

In response to an inquiry from the Northwest News Network and The Seattle Times, a McKinsey spokesperson noted that the company has supply chain experts, data scientists, program managers and individuals with public health backgrounds on staff.

“Our firm has the capabilities to support leaders and public servants who are navigating this humanitarian and economic crisis,” the statement said.

Officials with the Inslee administration said one of McKinsey’s dashboards tracked COVID mitigation measures in all 50 states, down to the county level, allowing them to see what was working elsewhere.

Another dashboard gave the governor and his staff the ability to look at the fallout from COVID-19 through three lenses: the impact to people’s health, to the state’s economy and on vulnerable individuals. For instance, the McKinsey tool would flag if a county saw a steep drop in consumer spending or a spike in drug overdoses or suicide attempts.

“From a visualization perspective it was really invaluable to see these three broad sets of data,” said Sheri Sawyer, a senior advisor to Inslee.

But Inslee staff couldn’t point to a specific decision by the governor that resulted directly from McKinsey’s analysis.

Instead, Sawyer said, McKinsey’s data helped provide a “fuller picture” of what was happening in individual Washington counties and nationally. Additionally, she said, the McKinsey tool was one of the data sets that factored into Inslee’s decision last month to halt alcohol sales at 10 p.m. and further restrict indoor dining at restaurants, among other new restrictions.

Additionally, in June, when COVID cases spiked in Yakima County and threatened to overwhelm local hospitals, McKinsey’s analytics were used to aid decision-making about the transfer of some patients to hospitals in western Washington, said Dr. Bono, the state’s health system response coordinator.

But a top legislative Republican expressed concern about the lack of competitive bidding or legislative oversight of McKinsey’s work for the state. Sen. John Braun, the ranking Republican on the Senate budget committee, also described the $165,000 per week contract with the governor’s office as “quite steep.”

“It sounds to me like, once again, kind of the high end, high-tech folks of the world are making out like bandits during this pandemic at the expense of everyone else,” Braun said.

Founded in 1926, McKinsey has been described by The New York Times as the “world’s most prestigious management-consulting firms.” In 2019, it ranked as the 11th largest global consulting firm with $8.8 billion in revenues, according to Consulting.com. But in recent years the company has faced criticism and scrutiny over its domestic and international client work.

In May, even as Washington state was retaining McKinsey, the federal General Services Administration cancelled its long-term, government-wide contract with the company. The move followed an inspector general report in 2019 that found improper pricing involving that contract cost the U.S. government an estimated $69 million.

A McKinsey spokesperson said the company was disappointed by that decision.

“We continue to serve federal, state, and local clients and stand by the quality and value of our work,” the spokesperson said.

McKinsey has also come under scrutiny for its role in advising the opioid industry, which the company said it no longer does.

Last year, ProPublica and The New York Times reported on McKinsey’s work with the Trump administration as it sought to crackdown on illegal immigration and speed the deportation process.

In a separate story, in 2018, The New York Times explored McKinsey’s work in China, Russia, Saudi Arabia and elsewhere and concluded “the iconic American company has helped raise the stature of authoritarian and corrupt governments across the globe, sometimes in ways that counter American interests.”

McKinsey has pushed back forcefully at the criticism. It said the reporting on its work with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement “fundamentally misrepresents McKinsey’s work.”

ALSO SEE: Coronavirus News, Updates, Resources From NWPB

Regarding its overseas consulting work, the company, in a lengthy statement, described the Times’ story as “a deeply misleading account of how we operate.”

In February of this year, The Atlantic magazine pointed the blame at consulting firms like McKinsey for playing a key role in hollowing out America’s middle class over the past 70 years.

“In effect, management consulting is a tool that allows corporations to replace lifetime employees with short-term, part-time, and even subcontracted workers,” The Atlantic wrote.

Asked whether McKinsey’s values align with Inslee’s, Postman, his chief of staff, said that issue had not come up.

“I’m not sure how to address that,” Postman said. “I certainly didn’t have those conversations with the governor about that company or other consultants.”

Technically, the contract between the governor’s office and McKinsey is in place through the end of the year. However, after the initial eight weeks elapsed on July 21, the governor’s office didn’t immediately renew its subscription to the McKinsey service. An Inslee spokesperson said “at this time” there are no plans to do so.

Related Stories:

COVID-19, 5 years later: Reflections on the scars we carry, and resilience in unprecedented times

NWPB caught up with local residents and doctors to talk about how they’ve moved forward following the COVID-19 pandemic. They spoke about how the experience changed them and wisdom they’ve gleaned along the way. These are their reflections.

US Supreme Court will consider petition for stay in COVID-19 free speech case

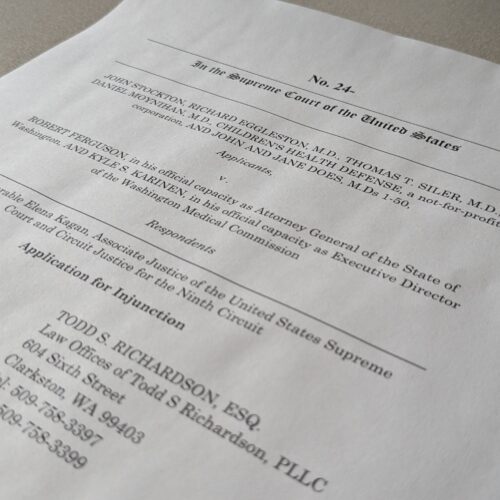

The U.S. Supreme Court will review an application for a stay in a federal lawsuit involving local retired eye doctor Richard Eggleston.

Group representing retired Clarkston ophthalmologist asks US Supreme Court for injunctive relief

A retired Clarkston eye doctor is part of a group asking the U-S Supreme Court to grant an injunction in a lawsuit against Washington state officials.