C.T. Vivian, Civil Rights Leader And Champion Of Nonviolent Action, Dies At 95

BY COLIN DWYER

For the Rev. C.T. Vivian, a jail cell was about as familiar as a police officer’s fist. For his work during the height of the civil rights movement, the minister and activist was arrested more times than he cared to count and suffered several brutal beatings at the hands of officers throughout the South.

All the while, he held fast to one principle: “In no way would we allow nonviolence to be destroyed by violence,” he recalled in an oral history recorded in 2011.

The Rev. C.T. Vivian, seen in a 2012 portrait at his Atlanta home, has died at the age of 95. CREDIT: David Goldman/AP

Vivian, who died Friday in Atlanta at the age of 95, was a proselytizer of nonviolent resistance. From Peoria, Ill., where he organized some of the civil rights movement’s first sit-ins in the late 1940s, to Selma, Ala., where a sheriff sucker-punched him on camera in 1965, Vivian bore the same message: Change must come, and nonviolent direct action is necessary to bring it about.

“He was one of the tallest trees in the civil rights forest,” Rev. Jesse Jackson tweeted Friday, calling Vivian a mentor. “He never stopped dreaming. He never stopped fighting. We are better because he came this way.”

Born Cordy Tindell Vivian, he cut his teeth as a young man organizing direct actions in Illinois before heading to Nashville. It was while he was there, in the mid- to late 1950s, that Vivian first worked with Martin Luther King Jr. and led a series of campaigns against segregation in the Tennessee capital.

Over the following decade, his efforts took him to Chattanooga, Tenn., Jackson Miss., and Birmingham, Ala., among other cities throughout the South.

He was a leading member of the Freedom Riders, a loose collection of activists who took rode interstate buses to protest segregated bus terminals — and often suffered beatings and arrests as a result.

Beginning in 1963, he served as the national director of affiliates for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. In that role, he became a key ally of Martin Luther King Jr. and a major organizer of civil rights actions across the South.

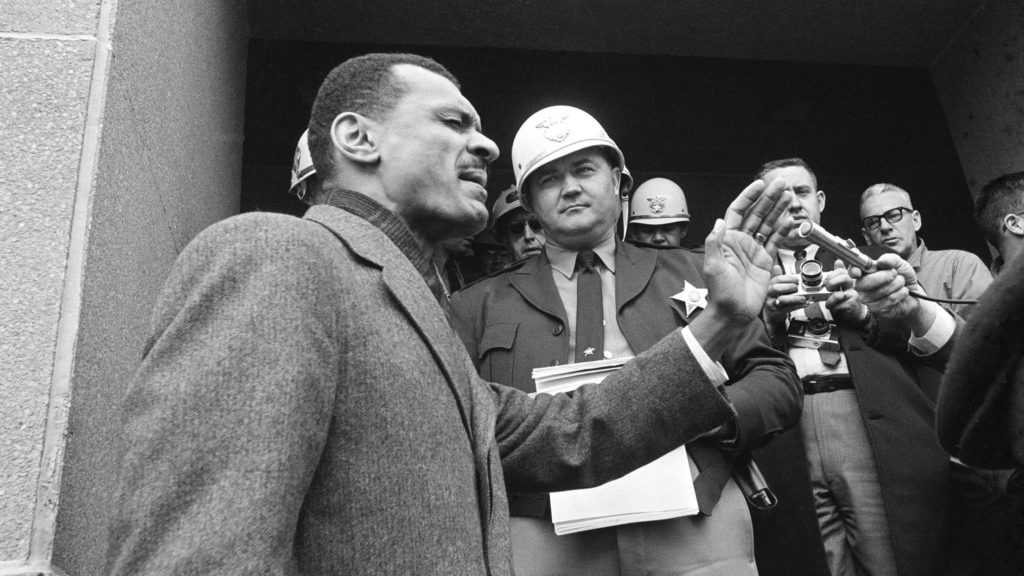

C.T. Vivian, leads a prayer on the steps of the the courthouse in Selma, Ala., in February 1965, after Sheriff Jim Clark (in a white helmet) stopped him at the door with a court order. During another confrontation on the same steps just days later, the segregationist sheriff punched Vivian to the ground — and Vivian stood back up to continue his argument.

CREDIT: Horace Cort/AP

“If it had Martin’s name on it or if it was SCLC-affiliated, I was over that and having to take care of it and deal with it,” he explained in 2011.

“He was one of those people who talked about strategy,” civil rights activist Josie Johnson told NPR’s Morning Edition, “talked about methods, talked about the rationale for having a plan. Not just acting, but understanding why you’re acting and then being consistent.”

It was also in his role as director of affiliates for SCLC that Vivian had perhaps his best-known confrontation with authorities. He had traveled to Selma to press for voting rights. There, on the steps of the Dallas County courthouse in February 1965, segregationist Sheriff Jim Clark blocked his path into the building.

So Vivian used the moment as an opportunity for a sermon of sorts.

“You can turn your back on me, but you cannot turn your back upon the idea of justice. You can turn your back now and you can keep the club in your hand, but you cannot beat down justice,” he told Clark, as the media recorded the encounter and several dozen protesters looked on behind him. “And we will register to vote, because as citizens of these United States we have the right to do it.”

Clark responded to Vivian with a punch in the mouth, knocking him to the ground. Vivian did not retaliate physically, but pulled himself to his feet and kept speaking as police shoved aside and ultimately arrested him.

Just weeks after the incident aired on national television, thousands of people gathered for the famous march from Selma to Montgomery. And before the year was out, Congress had passed the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Vivian received the Presidential Medal of Freedom for his work in 2013. But in an interview recorded for the honor, Vivian reiterated his call to action, saying that the work for racial and social justice was far from finished.

“Do what you can do and do it well,” he said. “But always ask your question: Is it serving people?”