How A Coronavirus Vaccine Will Get To Market

BY ISABELLA ISAACS-THOMAS / PBS NewsHour

With new daily case counts of novel coronavirus on the rise in nearly every state, as well as Puerto Rico, the consequences of reopening much of the country without first stopping the spread has made one thing clear: An unlocked United States will likely continue to suffer from the deadly virus until a safe and efficient vaccine is finally distributed to a majority of the population.

There are lots of different ways to formulate a vaccine, and all of them are now being considered for coronavirus. Some vaccines use common methods to confer immunity, while others are entirely experimental — they’ve never before been approved for use.

No matter the approach, academic, corporate and government research teams around the globe are coordinating with national and international agencies to move their candidates through preclinical animal trials and, for those with promising results, human trials. All of them aim to one day see millions, even billions, of doses of their vaccine manufactured and distributed to those in need — hopefully, sooner rather than later.

A doctor at Novavax labs in Gaithersburg, Maryland on March 20, 2020, works on developing a vaccine for the coronavirus. CREDIT: Andrew Caballero-Reynolds/AFP

But leading public health officials like Dr. Anthony Fauci have warned there is simply “no guarantee” that the ongoing national research effort will produce a successful vaccine in 12 to 18 months — a timetable he’s repeatedly laid out.

In testimony last week, Fauci, one of the leading members of the White House’s coronavirus task force, emphasized the unpredictable nature of vaccine development, while adding that he’s hopeful that a number of doses will be approved and available for distribution by the beginning of 2021.

“We are cautiously optimistic, looking at animal data and the early preliminary data, that we will at least know the extent of efficacy [for vaccines that go through clinical trials] sometime in the winter and early part of next year,” he said before the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions.

Vaccines normally go through around a decade of research and evaluation before finally being approved for commercial use. But public health officials have determined that the urgency of the pandemic demands a significantly expedited version of that process.

With any potential vaccine, researchers have to ask a series of questions: Does it successfully prompt a desired immune response in humans? Has it been shown to be both safe and effective? Can manufacturing be scaled up to meet the demand required by this crisis?

More dilemmas are likely to arise once a vaccine has been approved for use, one of the most crucial being which groups will be first to receive it, and how that decision will be made.

Here’s a look at some of the top vaccine contenders, as well as the challenges public health officials will face when that vaccine is finally ready for use.

How vaccines are developed

One of our immune system’s main attributes is that it can remember what viruses look like so that our cells know how to fight them off if they infect us again. When we’ve been vaccinated against a pathogen or exposed to it naturally, we usually suffer less severe symptoms, or none at all.

In the case of coronavirus, which is believed to have just recently evolved to infect humans, it’s not yet clear if, or for how long, a person who has survived COVID-19 is protected against reinfection. More conclusive antibody research is needed to determine whether those who have already had the virus will need a vaccine, or if those who do get the vaccine will eventually need booster shots as maintenance.

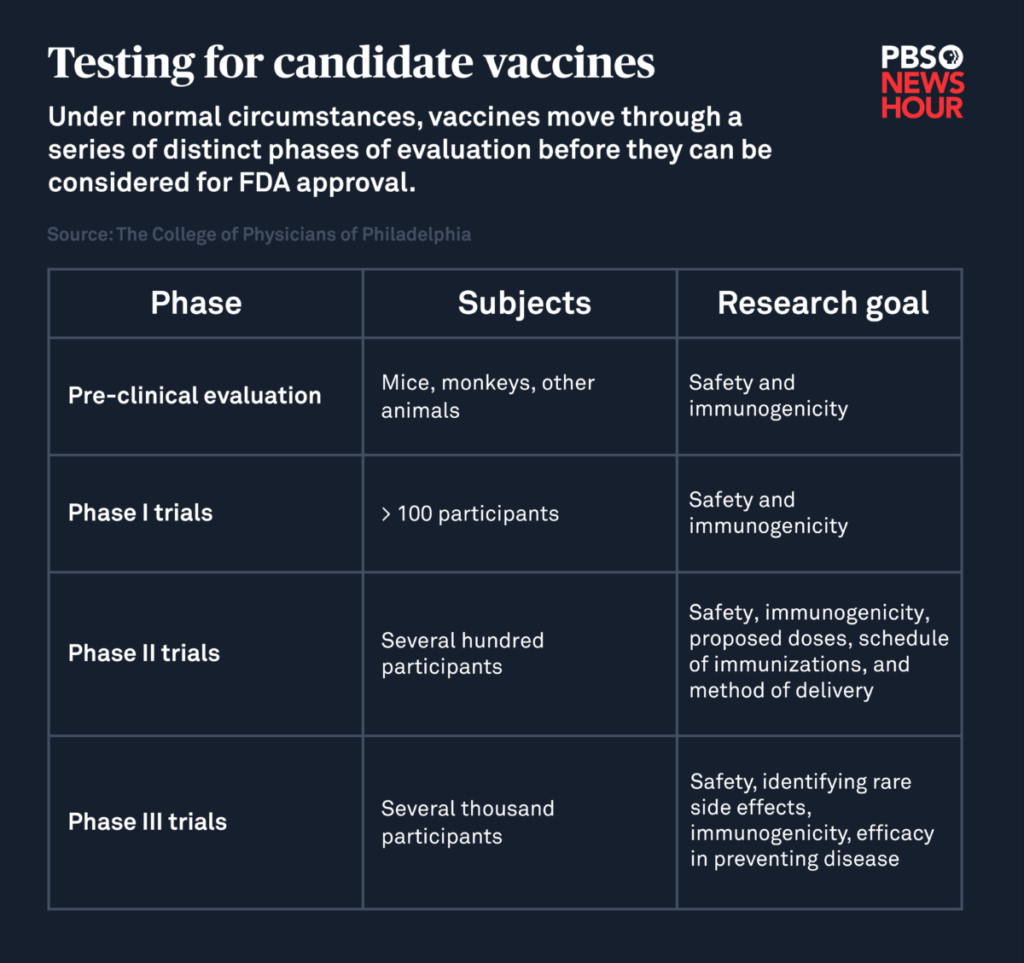

Under normal circumstances, candidate vaccines first go through preclinical trials in which animals like mice or monkeys are inoculated. Researchers then evaluate whether their bodies produced an immune response that would potentially protect against infection in humans, and look for any adverse side effects.

After that, successful candidates are eligible to be tested in humans. During the first phase of clinical trials, researchers give the vaccine to a small number of healthy adults to check for safety and immunogenicity, or the vaccine’s ability to prompt its desired immune response. The second phase of this effort, which involves several hundred volunteers, looks for any unwanted side effects and determines what dose produces the most effective immune response.

The third and final phase of vaccine testing continues to evaluate safety and effectiveness by inoculating thousands, even tens of thousands, of volunteers and determines how well the vaccine prevents infection while noting any rare side effects associated with it that didn’t become apparent during earlier phases.

If all of these steps are successfully completed, researchers can submit their data for review by the Food and Drug Administration’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research. That division is responsible for approving vaccines, overseeing their production and continuing to monitor them once they’re on the market. Only about 6 percent of candidate vaccines are ever approved for commercial use.

To identify a promising vaccine for coronavirus, researchers are instead evaluating all of these factors — safety, immunogenicity, efficacy, side effects — in parallel through trials that combine the phases of a typical vaccine development process.

During last week’s hearing, FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn emphasized the importance of including “racial minorities, the elderly, pregnant women and those with other health conditions” in large scale human trials to ensure that any vaccine moving through the approval process will be effective on populations most vulnerable to COVID-19. Pregnant people and the elderly or immunocompromised typically aren’t involved in trials like this, but have been identified as being at greater risk for severe virus outcomes, so researchers must ensure these vaccines protect them.

The Defense Department, one of the agencies partnering on the Trump administration’s national vaccine development initiative, has said that officials “expect to be producing large quantities of vaccines while the clinical trials are still underway,” so that there is no delay in manufacturing once “safety and efficacy have been demonstrated.”

Operation Warp Speed is aiming to “deliver 300 million doses of a safe, effective vaccine” by January 2021, according to the Department of Health and Human Services. In order to do that, billions of federal dollars are being allocated to scale up manufacturing of a handful of promising candidates before they’re actually authorized for distribution. It’s a financial risk that most private companies would be loath to take, but a necessary gamble for the government in the context of the pandemic.

Meet the candidates

Among the 21 global candidate vaccines currently moving through clinical trials, Operation Warp Speed has begun to single out a handful of contenders by offering them funding, including AstraZeneca, Moderna and Novavax and Johnson & Johnson. The criteria for how those companies were chosen is not fully clear, a concern that lawmakers have pointed out and pushed Trump administration officials for answers. Here’s what we do know:

AstraZeneca: The vaccine, developed by researchers at the University of Oxford, is a modified adenovirus that mimics the new coronavirus’ spike proteins, which are what allows the virus to invade human cells. When introduced to the human body, the vaccine aims to prompt the creation of antibodies that would neutralize the actual coronavirus and prevent it from entering an infected person’s cells. Phase 3 trials recently kicked off in Britain, Brazil and South Africa.

WATCH: Meet people volunteering to be exposed to COVID-19 for vaccine research

Last month, AstraZeneca announced that it had reached an agreement with the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations and Gavi The Vaccine Alliance to “support the manufacturing, procurement and distribution of 300 million doses” of its vaccine, and that delivery would start by the end of this year. The company also said that it would partner with the Serum Institute of India to “supply one billion doses for low and middle-income countries, with a commitment to provide 400 million before the end of 2020.”

Moderna: This candidate vaccine injects messenger RNA into the body that cells then translate into antigens resembling the coronavirus’ spike proteins, which intend to prompt the creation of antibodies that would neutralize the new coronavirus if a vaccinated person were to be infected.

Vaccines that use messenger RNA to provide immunity have never been approved for human use, but several are being tested to protect against COVID-19. If Moderna’s makes it to the finish line, it’ll be the first of its class to do so. A phase 3 study involving 30,000 volunteers is set to begin this month, and Moderna has partnered with the Swiss pharmaceutical company Lonza to manufacture approximately 500 million, but potentially up to 1 billion, doses per year.

Part of the appeal of Moderna’s vaccine is that messenger RNA is easy to make and not very stable — it disintegrates quickly in the body, which means it’s fairly safe. But that quality could also make an mRNA vaccine difficult to distribute widely. mRNA needs to be stored at around negative 80 degrees Centigrade — a much lower temperature than most other vaccines — which infectious disease expert Paul Offit pointed out would be difficult to accommodate in many settings.

Novavax: The biotechnology company announced this week that Operation Warp Speed had pledged $1.6 billion to support late-stage clinical testing of the company’s candidate vaccine, which is currently moving through a combined Phase 1/2 clinical trial. Novavax expects to see “preliminary” results regarding the vaccine’s safety and immunogenicity by the end of the month.

According to Novavax, its vaccine combines recombinant nanoparticle technology to create an antigen “derived from the coronavirus spike protein” with an adjuvant, or a compound that enhances the body’s immune response.

Johnson & Johnson: Johnson & Johnson’s candidate vaccine combines “genetic material from the coronavirus with a modified adenovirus” in order to prompt a protective immune response, according to CNBC News.

In June, Johnson & Johnson announced that it expects a combined Phase 1/2a clinical trial of its vaccine involving over 1,000 healthy adults to begin in the U.S. and Belgium later this month. The company said that the trial will evaluate safety, immunogenicity and reactogenicity, or response to vaccination, and that it’s currently “in discussions” with the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases to start a Phase 3 trial, “pending the outcome of Phase 1 studies and the approval of regulators.”

Dr. Soumya Swaminathan, chief scientist at the World Health Organization, recently identified AstraZeneca’s vaccine as “the leading candidate” of the vaccines currently undergoing clinical evaluation. She added that Moderna’s vaccine is “not too far behind,” and that at least four Chinese companies are preparing to kick off large scale Phase 3 trials for their candidates — one of which was recently approved for military use in China.

While those two candidates appear to be among the top contenders, a lot could change between now and the end of this year, let alone by the end of 2021, in the search for a viable coronavirus vaccine.

Experts also warn that the first vaccines may not be effective in completely preventing COVID-19 infection.

The chair of the United Kingdom’s vaccine taskforce, Kate Bingham, has said she expects that the first coronavirus vaccines to prove safe and effective may “help alleviate the symptoms” of COVID-19, rather than conferring full immunity, The Guardian reported last week.

That’s a prediction echoed by Offit, who explained that early vaccines will aim to reduce a person’s likelihood of developing “moderate to severe disease,” but might not protect against reinfection or mild symptoms associated with coronavirus.

“The goal of this vaccine is going to be to keep you out of the hospital and keep you out of the morgue,” Offit said.

Who will be first to get the coronavirus vaccine?

In order to restore a degree of normalcy to U.S. lives without constant fear of a resurgence, Fauci has said that between 70 to 85 percent of the population will need to be immunized against coronavirus. That will grant the nation “herd immunity,” which occurs when a large enough portion of a population is immune to a disease that they indirectly protect those who are not immune.

Dr. Robert Redfield, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, estimates that between 5 to 8 percent of the U.S. population has been infected with coronavirus so far. He emphasized during last week’s Senate hearing that it would take several years to achieve herd immunity through natural exposure, hence the urgent need for an effective vaccine.

For many countries, financial challenges may make it difficult to afford the millions or even billions of doses needed to vaccinate their populations. Vaccines need to be kept at a strict temperature range to remain effective, which could make mass distribution a challenge in many parts of the globe given the volume of doses that this crisis demands.

Lois Privor-Dumm, director of policy, advocacy and communications at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health’s International Vaccine Access Center, said that the moral question of who to vaccinate first is a difficult one, but that most agree that health care workers are “very high priority” due to their increased risk of exposure.

She emphasized that we must also consider how to make the vaccine available to undocumented people, low-income people, those experiencing homelessness, and other populations that often struggle with health care access. People in these situations, she noted, can be the same ones doing essential work in their communities, putting themselves at greater risk of infection.

Another challenge will be ensuring that vaccines are effective in seniors, whose immune systems generally don’t respond as efficiently to immunization. Offit said that it will therefore be important to immunize people who frequently interact with elders, such as home health workers and nursing home staff.

Maria Elena Bottazzi, associate dean at the Baylor College of Medicine’s National School of Tropical Medicine and co-director of Texas Children’s Center for Vaccine Development, said that any vaccine that’s approved for use will have to meet a series of “major requirements.” It must induce the correct immune response, and have the best safety profile possible. In order to be distributed widely, it will need to be capable of being manufactured at large scales.

She also noted that after a vaccine is developed and brought to market, there are “always second [and] third generation” iterations that seek to improve upon the original.

“Once an initial vaccine is launched and licensed, there’s a lot of what we call ‘postmarketing surveillance,’” which eventually leads to better vaccines, Bottazzi explained. Continuing to monitor a vaccine can also reveal any rare negative side effects.

Due to cost and manufacturing limitations, she envisions a “toolbox” of initial vaccines, some of which are more accessible to a wide range of nations, while others may only be available in wealthier countries.

Multiple lawmakers have raised concerns about the affordability and availability of an eventual vaccine. Sen. Bernie Sanders pointed out in last week’s hearing with leading health officials that billions of taxpayer dollars are funding pharmaceutical companies in their effort to develop a vaccine. He asked, given the significant of that investment, if every person in the country can expect to have access to an eventual vaccine regardless of their income.

All four public health officials present during the hearing — Fauci, Redfield, Hahn, Redfield and Assistant Secretary for Health Adm. Brett Giroir — answered Sanders’ question affirmatively.

Once a vaccine is finally approved, manufactured and available for widespread distribution, the question then becomes whether individuals and families want to be inoculated. A recent poll from The Associated Press and the NORC Center for Public Affairs research found that just 49 percent of people in the U.S. plan to actually get an eventual COVID-19 vaccine.

The poll also found that 40 percent of Black people and 23 percent of Hispanic people don’t intend to get vaccinated at all. In the case of the Black community, that stance may be in part rooted in general mistrust of the medical establishment. Black Americans have long suffered from lack of access to quality medical care, and even outright abuse at the hands of researchers.

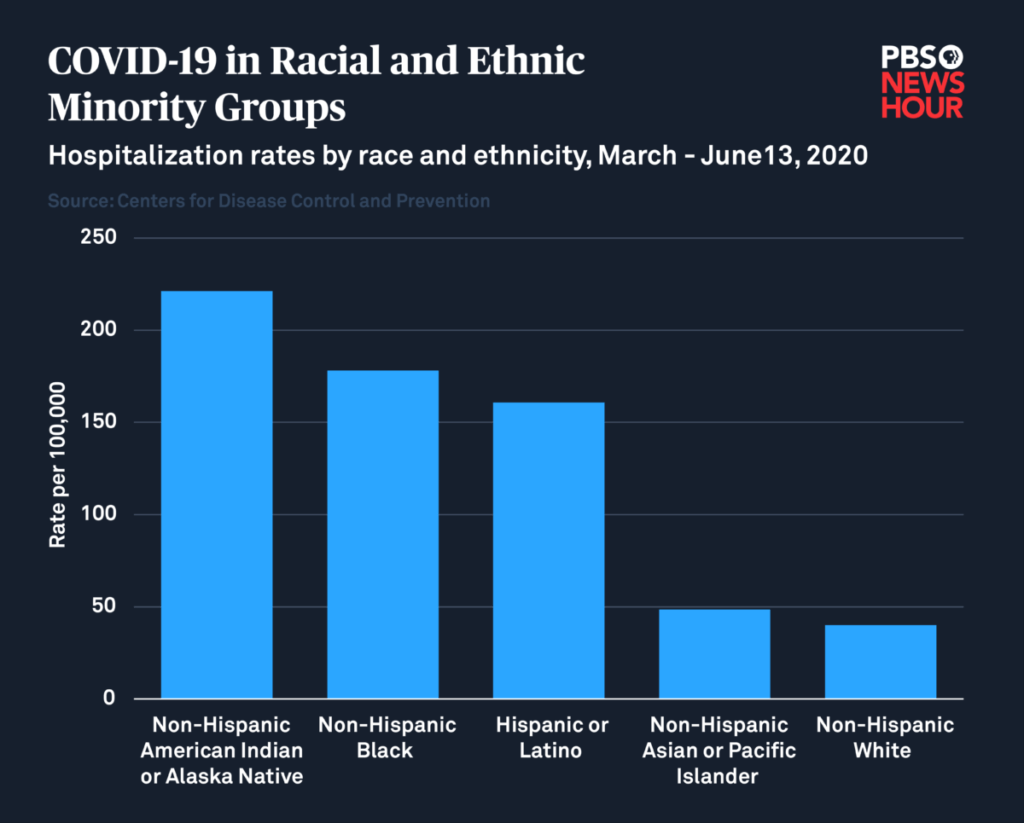

But in the context of the pandemic, those numbers are troubling, given that Black and Hispanic individuals, in addition to Native people, are four to five times more likely to be hospitalized due to COVID-19 infection. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention states that “long-standing systemic health and social inequities” are responsible for putting marginalized people at an increased risk of experiencing “severe” illness due to the virus, regardless of age.

During his testimony on Tuesday, Fauci pointed to a community engagement arm of Operation Warp Speed, echoing the concern that a “substantial” portion of the population, particularly those most at risk for serious disease, will be unwilling to receive the vaccine. He emphasized the need for trusted figures to engage with their communities and help spread accurate information regarding the importance of vaccination, citing the role that kind of outreach played in mitigating the AIDS crisis.

“We used people in the community — boots on the ground — to go out, who looked and lived and are like the people they’re trying to engage,” Fauci said, adding that such local engagement is “critical” to build the trust that will ultimately save lives.

So, while a coronavirus vaccine is still months — possibly years — away, public health officials know that the time now to start building the public’s confidence.

Copyright 2020 PBS NewsHour. To see more, visit pbs.org/newshour