‘The Perfect Time For Change’: Tri-Cities Protests Recall Past Police Shooting, Racist History

Listen

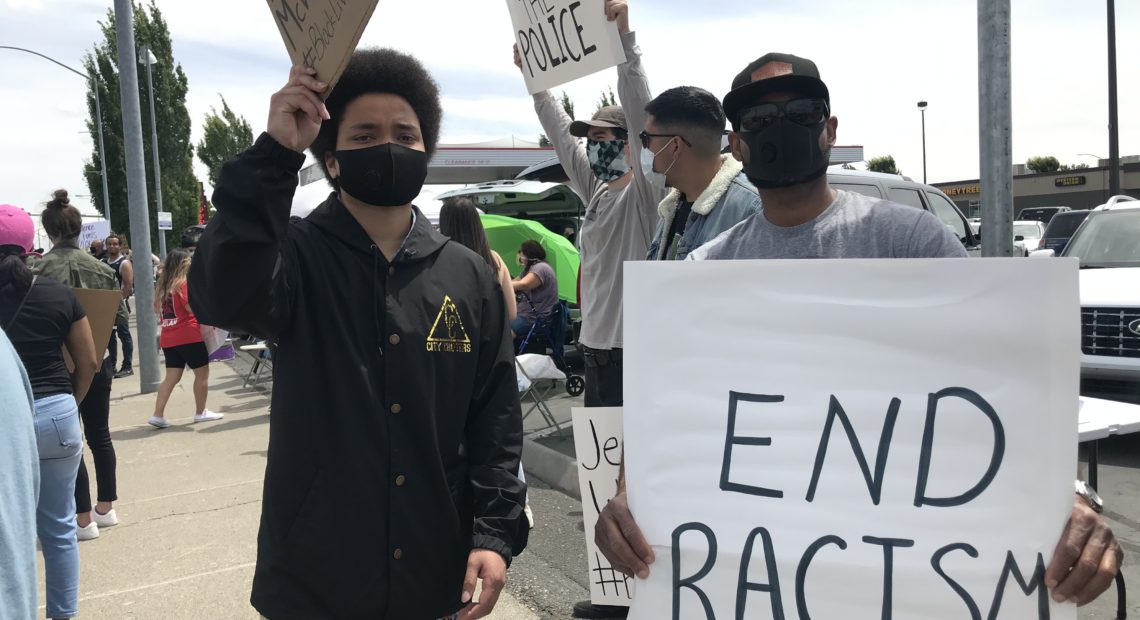

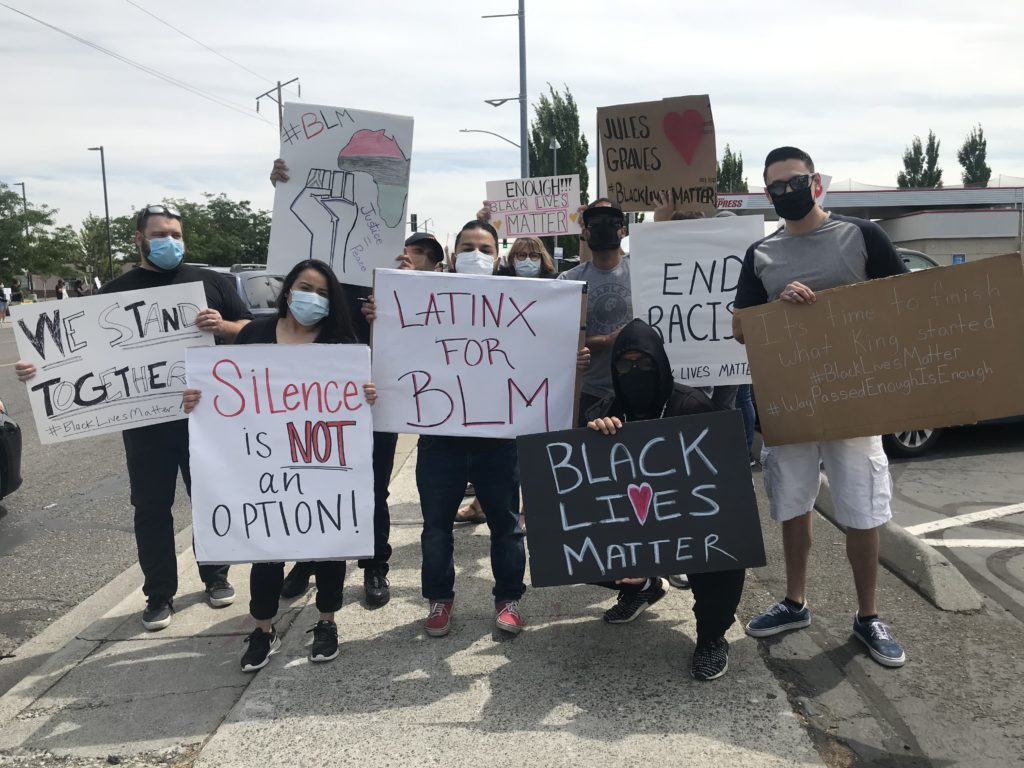

Hundreds of people lined both sides of Court Street in Pasco recently, standing shoulder-to-shoulder, chanting “Black Lives Matter,” “No Justice, No Peace,” “Say His Name: George Floyd.” Fists raised in the air, signs shouting the names of the last 100 people killed by police or vigilantes and white supremacists.

The moment is perhaps more poignant in Pasco, where five years ago, the city reeled from its most high profile police shooting. The killing of Antonio Zambrano-Montes and the fallout after have marked this city, in murals and memorials, in police interactions and protests.

Add to that: A history of racism the Tri-Cities often tries to forget.

Boiling Point

It all came to a boiling point with the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery during a global pandemic, said poet and educator Jordan Chaney.

“I feel like even God and the angels must have set it up for us to really look at what it looks like to see a Black person get killed on camera and nobody do anything about it. No justice to be served,” Chaney says.

In Pasco, protest leaders read off the names of the last 100 people killed by police, with corresponding signs demonstrators carried. Even though not all of these people got protests of their own, they all deserved justice, Chaney says.

“I think a lot of times, when we are screaming ‘justice’ with angry voices, people don’t see the dead bodies we are trying to defend. They also think that this ‘justice’ notion, idea and intention somehow equates to revenge. Justice is not revenge,” Chaney says. “Justice is equality. Justice is what love looks like in public.”

Justice is what people lined the streets for, when they protested the killing of Antonio Zambrano-Montes. Chaney says time feels different. Perhaps, Zambrano-Montes primed this city for more change.

A memorial to Antonio Zambrano-Montes in February 2015 outside of Vinny’s Bakery in Pasco marks the spot where he was shot and killed by Pasco police. CREDIT: Scott A. Leadingham

In 2015, officers were called to the corner of Lewis Street and 10th Avenue on the edge of downtown Pasco. A man had been seen throwing rocks at passing cars.

Zambrano-Montes continued to throw rocks as police confronted him. The Tri-City Herald would later report that an officer tried to shock Zambrano-Montes with a Taser, but he didn’t respond. The first officer at the scene also tried to “center kick” Zambrano-Montes, the Herald reported.

The three responding officers said they worried they would be hit by a large rock. So, they began shooting. They fired 17 times. Zambrano-Montes was struck up to seven times.

In the days and week following, protesters marched through Pasco, demanding justice and asking for the three officers to be charged with murder.

Local, state and federal prosecutors declined to criminally charge the three officers. In a rare fact-finding inquest by the Franklin County Coroner, a jury also found the officers were justified in the shooting.

The family was awarded a $750,000 settlement for a federal lawsuit filed against the city, the Pasco Police Department, then-Police Chief Bob Metzger and the three officers.

In separate reports, ACLU of Washington and the Department of Justice recommended changes for the police department. A year later, the DOJ said the Pasco Police Department had indeed improved.

Hard-Fought Start

It was a hard-fought start, says Felix Vargas, with Consejo Latino. After the Zambrano-Montes shooting, Vargas and other community leaders sat down with the Pasco Police Department.

“It really tore this community apart. It caused us to look deep into ourselves and see what it is we wanted in our community and what it is we expected from our law enforcement officers,” Vargas says.

Vargas says that after lots of daylong discussions, “It spoke well of the city to recognize the importance of change, embracing it, talking to people and bringing about the change.”

That’s something the police department has worked hard to do, according to current Pasco Police Chief Ken Roske. He came into his new role in the department in 2019, but he was said to be instrumental in helping rebuild community relations after Zambrano-Montes was killed.

Protesters in Pasco lay on the sidewalk for 8 minutes and 46 seconds, the amount of time a Minneapolis police officer pressed his knee into George Floyd’s neck. CREDIT: Courtney Flatt/NWPB

Roske says community trust was one of the biggest issues to tackle. He says the department works harder than ever to partner with the community – there are now more area resource officers that focus on neighborhood problems (known commonly as community policing. The department first adopted as a practice in the 1990s.) These officers handle a gamut of issues, from helping with facilitating code enforcement to domestic violence situations.

“They’re long-term problem solvers,” Roske says.

Officers take courses like implicit bias training. There are now programs, such as Coffee with a Cop, to help break down barriers, Roske says. A restructured citizens’ academy, body cameras and a large, often viral social media presence.

The department also updated its use of force policy. It clarified steps officers considered obvious but that citizens might not have known about, Roske says, like caring for someone who has been injured in police custody. Officers have also been equipped with tourniquets and rescue training.

If Zambrano-Montes was throwing rocks today, Roske says: “ … the tragedy of the incident may not change. But from a transparent standpoint, as the police department, we learned an awful lot of lessons.”

It would be important to let an independent investigation proceed, Roske says, but the police department should have been more transparent from the beginning. “I think you wouldn’t have had as many of the public questioning police legitimacy and accountability for the police.”

Roske believes the recent “anti-police rhetoric” is concerning. He says there is “no thought of removing resource officers from (Pasco) schools,” as has been pushed for in other cities. He also strongly disagrees with calls to defund police departments.

Roske condemned the killing of George Floyd. “A couple of officers made some horrendous mistakes, and maybe they were intentional,” he says. “There is not – that I am aware of – a law enforcement organization, a police chief or a career officer who has not right out denounced what happened in Minnesota.”

“The Birmingham Of Washington”

This week, Gov. Jay Inslee proposed restricting chokeholds in Washington. He also called for an independent state unit to investigate officer-involved killings and a “legally enforceable” requirement for officers to report colleagues’ misconduct.

“This is a moment unlike anything we’ve seen. It’s a moment to do things differently, to do them better, and to do them with a real commitment to change,” Inslee said at a news conference.

Changes like restricting chokeholds would meet the absolute barest of minimums needed, says Dallas Barnes, a longtime Pasco resident. Barnes, who is Black, moved to Pasco in 1952 at age 12 – the same age as Tamir Rice when he was shot and killed by police in Cleveland 62 years later.

Jordan Chaney (carrying the black sign) stands with a group of protesters in Pasco. “Justice is equality. Justice is what love looks like in public,” he says. CREDIT: Courtney Flatt/NWPB

In the Tri-Cities, the pain people feel goes far beyond the recent deaths, Barnes says. The pain reaches back into the area’s history. In 1963, civil rights leaders would dub Kennewick “the Birmingham of Washington,” according to a Tri-City Herald article.

“What people want to do right now is to talk about the problems that are going on. Those of us who have been around for a while are saying, ‘Are you kidding?’” Barnes told NWPB in a recent interview. “What do you think the protest of the ’60s was all about? What do you think the slave uprisings were all about? What do you think the Civil Rights bill was all about?”

When Barnes moved here, East Pasco was the side of town where Black and minority residents were “encouraged to live.” Barnes lived just over the border of the train tracks in West Pasco.

“It was close enough to eastside that I suppose it was considered eastside,” he says.

At that time, Kennewick was known as a “sundown town,” meaning Black people had better be across the green bridge and into East Pasco before nightfall. A sign on the bridge made clear the warning.

“You were not welcomed in Kennewick. You were not welcomed in the white community, wherever that community was at,” Barnes says. “You certainly were not welcome in certain places if you didn’t have on an apron or a pair of overalls, suggesting that you worked in those communities as opposed to living in those communities.”

He said that history still echoes today – as armed people line up in parking lots in Kennewick and along protest marches in Moses Lake and other areas off the Northwest.

Barnes said he’s attended too many protests to count in his lifetime: from demanding Black cashiers be able to work at stores in downtown Pasco to grief and outrage after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

All these years later, he says policing hasn’t changed much in his eyes. One thing that would help: training that addresses underlying systemic and historical issues.

“I don’t necessarily see very much to improve (police) understanding of what makes the ‘bad guy,’ and the conditions which produce the turmoil that we are experiencing now,” Barnes says.

He does see some hope, though.

“Whoever is out there protesting,” he said. “I think I added two, three year to my life when I saw that.”

“The Perfect Time For Change”

At the Pasco demonstrations, several people said recent changes to the Pasco Police Department since Antonio Zambrano-Montes was killed are noticeable, although more is still needed.

“Prior the Antonio Zambrano death, murder, I feared every single cop I saw. Every time I would see a cop, man, I think of my son, and I think of my mom. And I think, ‘OK, who do I need to talk to you before I might get shot?’” poet Jordan Chaney says. “Because I’m not quiet about my blackness, man. I bump my hip hop music. I got a cool-ass haircut. I don’t want to be quiet about my life. I ain’t going back to code switching.”

Daishaundra Loving-Hearne helped organize the Pasco protest. She says she will keep fighting for police reform, long after the people leave the streets. CREDIT: Courtney Flatt/NWPB

Now, he said, he’s no longer nervous driving by the Pasco police.

But, protesters are going to continue to demand changes. It won’t be an overnight issue.

“We are going to need an open door policy,” Pasco resident Daishaundra Loving-Hearne says.

Just as she began to answer a question about Pasco police, three police cars drove by the protest, sirens flashing. Officers honked their horns and waved in support.

“The police are passing us in a parade,” Loving-Hearne smiled as she watched them. “That’s awesome. That’s just awesome.”

Later in the protest, the entire sidewalk laid down or kneeled for 8 minutes and 46 seconds, the length of time Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin had his knee pressed to George Floyd’s neck.

“It’s been a long time coming, but I know, change will come. Oh, yes it will,” Sam Cooke sang through speakers and cars honked as they passed.

Loving-Hearne says she’ll continue her push for policing reform, long after people have left the streets, gone back to work and school.

“I personally believe that you can’t heal anything that you’re not willing to look at. You can’t heal a wound if you’re not willing to look at it and expose it,” Loving-Hearne says. “Right now, this is just the perfect time for change.”

Related Stories:

See Ya! Washington Police Say Drivers Aren’t Stopping For Them; Cite Pursuit Restrictions

Since January of this year, more than 900 drivers have failed to stop for a Washington State Patrol trooper trying to pull them over. The patrol and other police agencies around the state say they’ve never seen such blatant disregard for their lights and sirens. The change in driver behavior comes after state lawmakers passed strict new rules on when police can engage in pursuits.

Police Say It’s Hands Off For Some Mental Health Cases After Washington’s New Use Of Force Law

In Washington, the working partnership between police and crisis mental health workers is being put to the test. The reason is a new police use of force law.

Murder Charges Filed Against Tacoma Police Officers In Death Of Manuel ‘Manny’ Ellis

The Washington state attorney general on Thursday charged two Tacoma police officers with murder and one with manslaughter in the death of Manuel Ellis, a Black man who died after repeatedly telling them he couldn’t breathe as he was being restrained.