‘Public Health Has Been Politicized’: Spokane Case Highlights Complexity In Quarantine Orders

Listen

When Mordecai Cochrane was found passed out behind the wheel of his Toyota Avalon by Spokane police in the dead of night, he’d been tested for coronavirus the day before, but was waiting for results.

Five days later, he was back behind the wheel, driving at night with his lights off and with too many people in the car. Cochrane again encountered police. This time he had his test results. He’d tested positive, had no symptoms and was contagious.

Six officers who dealt with him during his two DUIs are in isolation. So is Cochrane, but only after being forced to stay home by the county’s public health officer.

The 21-year-old, who is separately awaiting trial in North Idaho on two counts of rape, is among the first people in the state to be forcibly isolated because of their COVID-19 status.

Contagious people in quarantine

As the coronavirus pandemic continues across the world, local health officials in Washington are beginning to employ a power given to them by state law that allows to keep contagious people in quarantine.

Dr. Bob Lutz, Spokane’s public health officer, says the law gives him and his colleagues “very broad authority” during contagious disease outbreaks.

“It’s not something that we do often. It’s not something that we do lightly,” he said. “We always like to use the path of least resistance, and strongly encourage people to do the right thing and self-isolate or self-quarantine so that they can protect others. And in certain situations for any number of reasons, people aren’t either able or willing to do that.”

It’s an extraordinary power. But these are uncommon times.

Terry Preuninger, a sergeant with the Spokane Police Department, has been with the force for 28 years. Cochrane’s case is the first time he’s seen the public health authority used.

“I started in 1992, it’s the first one I’ve seen,” he said.

‘You’d much rather use a carrot’

Protesters have been turning up around the state to rail against Gov. Jay Inslee’s public health measures, calling him “tyrant.”

But, in the case of quarantines, the power lies elsewhere.

Mike Faulk, Inslee’s spokesman, says the governor doesn’t have the authority to force people into isolation.

“First, the governor does not have an isolation/quarantine order in place right now,” Faulk wrote in an email. “So, in the absence of that, both local health officers and the state secretary of health have authority to issue isolation and quarantine orders under current law.”

That law, officially, is part of the Washington Administrative Code, chapter 246-100. It gives local health officers the power to detain people “at his or her sole discretion.”

But there are limits.

Health officers must first seek voluntary compliance. If the officer wants the person to be isolated for longer than 10 days, they must get a judge’s permission. And they are “legally required to provide every isolated or quarantined person with regular health monitoring and adequate food, clothing, shelter, means of communication, medication, and medical care.”

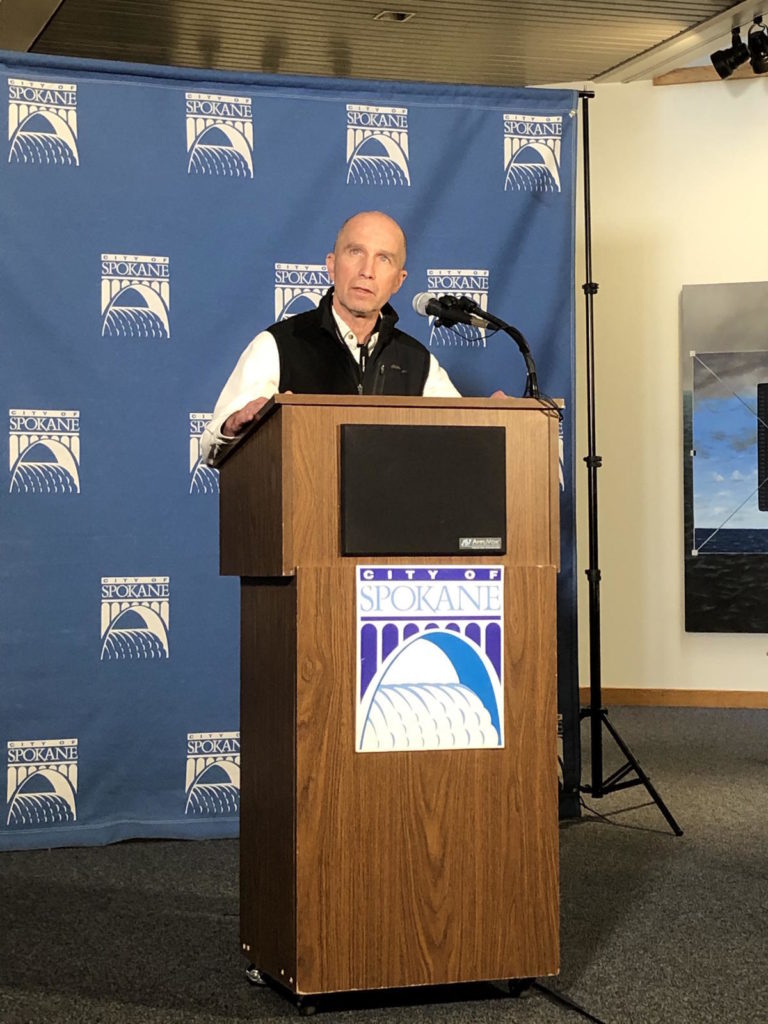

Spokane County Health Officer Bob Lutz has been the face and voice of the county’s coronavirus response briefings. CREDIT: Doug Nadvornick/SPR

Lutz says he’s abiding by the law, and is working with the Spokane Alliance to provide such care. Still, it’s not his preferred route to keeping the community healthy.

“It’s a stick, but it’s a stick that you don’t like to use,” he says. “You’d much rather use a carrot.”

The state secretary of health has the same powers to force quarantine as local health officers.

Inslee does not. But he could.

If Inslee issued a proclamation directing people to stay in quarantine or isolation, he wouldn’t have to first seek voluntary compliance or get a court’s permission to extend the order beyond 10 days. And people who ignored his order could be arrested and cited with a misdemeanor.

Depending on the course of the disease, that order may come. For now, the authority remains in the hands of health officials.

During the current pandemic, Lutz has used the power, as has Dr. Chris Spitters, who leads the Snohomish County Health District, according to Lutz. Calls to confirm Spitters’ use of the authority were not returned by Friday afternoon.

‘Why are you pulling us over?’

Cochrane was asleep for more than four hours, his car running the whole time, before Spokane police showed up May 20 at 3:30 a.m.

He was slumped over the wheel, and after officers rustled him awake, he said he’d drank a fifth of whiskey and didn’t know where he was. He was arrested and spent 12 hours in jail.

After his release, he got the results from the test he’d taken the day before. He tested positive, just like many of his co-workers at the Philadelphia Macaroni Co., the site of the city’s largest outbreak. Half the employees there tested positive as did others connected to the factory, leading to at least 50 people with confirmed cases.

On Memorial Day, five days after his first arrest, Cochrane was back behind the wheel of his car, driving through downtown just before 11 p.m. with “no tail lights illuminated” according to a police report.

As a police officer approached the car, one of Cochrane’s passengers leaned out of the window, and said, “why are you pulling us over?”

“His speech was very slurred and it was apparent that he was under the influence of an intoxicant,” the officer wrote in his report.

Again, Cochrane got a DUI, his second in five days. But he didn’t tell officers about his positive COVID-19 diagnosis until about halfway through their interaction with him. This time, Cochrane’s positive test result kept him out of jail.

But it didn’t keep him out of trouble.

Two days after his second DUI, Lutz issued what’s called an “emergency involuntary detention order for purposes of isolation.”

By this time, Lutz was confident his order was lawful. The authority has been used before, most commonly with people who have tuberculosis. It was also used “way back when, back in the ‘80s with the very first cases of HIV and AIDS when it was poorly understood,” Lutz said.

Regardless, in early March, Lutz and Michelle Fossum, legal counsel for the Spokane Regional Health District, went step-by-step through the process of ordering such an isolation. This was before the city had its first confirmed COVID-19 case on March 14, but after the state’s first case on Jan. 21. Lutz and Fossum created a “template” for the procedure, Lutz said, and ran it by officials in Spokane County’s Superior Court.

Two months later, with Cochrane out and showing “poor judgement,” Lutz used his authority for the first time.

He issued his order the evening of May 27, not quite 48 hours after Cochrane’s second DUI, and sent it to the police department.

“Once the emergency involuntary detention order was put out, we then began to try and locate him,” Preuninger says. The police contacted his family and friends, but Cochrane wasn’t at home.

The next morning, Thursday, Cochrane heard the news. His actions and mugshot were being reported by local media, and shared on social media. He called Lutz’s office, and spoke to an epidemiologist.

“He realized that he needed to stay home,” Lutz said. “There were a number of situations why, explanations-slash-excuses, as to why he didn’t, but he realized the ramification of not staying at home in isolation, and was planning and willing to do so. And we were planning and we did check up on him to make sure that was taking place.”

Lutz says that by this time, Cochrane was largely no longer a COVID-19 risk to the community. His test had taken place May 19. He called Lutz’s office on May 28 — nine days later and one day short of how long Lutz could legally isolate him.

‘Public health has been politicized’

Lutz says Cochrane’s actions are a matter of “poor judgement.” And Preuninger, with Spokane police, says Cochrane’s arrest has nothing to do with the virus.

“We just want to really emphasize: Each of the arrests of this gentleman earlier had nothing to do with COVID-19. They were for committing crimes related to drinking and driving,” he said. “We are not arresting people at this point for testing positive for, or for not social distancing.”

But Lutz laments the course public discussion has taken around the pandemic.

“Public health has been politicized. This whole pandemic has been, unfortunately, very politicized. It’s not following the science. It’s not following the data,” Lutz said. “Like the whole thing with isolation and quarantine. It’s no different than any other contagious disease. If somebody has influenza, we tell them to stay home. If somebody has pertussis, we tell them to stay home. It’s no different but because it’s been so heavily politicized, all of a sudden when we’re telling people that they should isolate during time which they’re contagious, all of a sudden it’s government overreach.”

Lutz defends his own actions as well as those of Inslee, calling the governor’s approach to the pandemic “calibrated” and “thoughtful.”

“He understands the science,” Lutz said. “That science needs to be the final decision maker. Not politics.”

While Lutz says his actions are “bread and butter public health,” he can’t help pointing out the “ironies” of some behavior and suggests a kind of selfishness among people.

“During wildfire season, nobody has any problems wearing masks. Everybody wants a mask. Everybody wants an N95,” he said. “We see people wearing around N95s, because it’s about them, versus wearing face coverings during COVID because it’s about somebody else. Because I’m protecting somebody else. It’s an interesting dichotomy. If it’s about you, you’re willing to wear a mask. If it’s about somebody else, you’re not willing to wear a face covering.”

Related Stories:

Washington, Idaho rank high for public health emergency preparedness

Both states saw steady or increased funding for public health, but Idaho still among lowest for vaccinations.

Health district secures grant funds, distributes response survey after Lineage warehouse fire

Fire crews spray water on rubble at the Lineage Logistics fire in Finley, Washington. The fire started on April 21. (Credit: Benton County Fire District 1) watch Listen (Runtime 1:08)

Medication first, and then a whole-health approach

A couple of blocks off U.S. Route 12 in Walla Walla, Blue Mountain Heart to Heart has been treating people with substance use disorder for over a decade. But, for years, the nonprofit was unable to quickly offer a proven treatment for opioid use disorder: medication-assisted treatment.

Staffers would have to arrange for patients to get an assessment with a trained substance use professional elsewhere to start the medication. Getting that assessment, and then, getting started on the medication, buprenorphine, used to take weeks.