Federal Rollback Of Environmental Rules Continue Despite Pandemic. Opponents Cry Foul

LIZ RUSKIN, CASSANDRA PROFITA & JENNIFER LUDDEN

Do public hearings over Zoom unfairly suppress opponents’ comments, or allow even more people to engage?

That’s just one point of dispute as the Trump administration pushes ahead with some of its most controversial environmental policy changes this spring despite the coronavirus pandemic. November’s vote is driving momentum, since policies finalized too late could be overturned more easily should President Trump lose re-election or Democrats gain control of the Senate.

But environmentalists, state regulators and lawmakers say the public is distracted by the coronavirus pandemic. They’ve asked the government to hit pause on a host of proposals, with little success so far.

Because of the pandemic, the Bureau of Land Management held virtual public hearings in April on a proposal to expand oil drilling in Alaska’s North Slope.

U.S. Department of the Interior / screenshot by NPR

Recently finalized rules include scaling back regulations for fuel efficiency in cars and trucks, air pollution coming from power plants and water pollution in streams and wetlands. The administration is also pushing ahead with a string of more localized policies, such as expanded logging and oil drilling in Alaska.

“It really switched the power dynamic”

In April, the Bureau of Land Management canceled in-person meetings and instead held eight Zoom sessions on a plan to develop as many as 250 oil wells in the National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska.

“It really switched the power dynamic, incredibly, during these hearings, in terms of who had the control,” says Nicole Whittington-Evans, Alaska director for Defenders of Wildlife.

She complains that one man’s microphone was muted as he was providing his opinion. Whittington-Evans acknowledges the man was swearing and probably would have been asked to leave an in-person meeting. But “you can’t just, like, hold your hand over somebody’s face in a public hearing,” she says.

During the Zoom sessions many opponents of the drilling plan complained that the hearing format was unfair.

But BLM spokeswoman Lesli Ellis-Wouters says Zoom hearings actually have some big advantages. One meeting drew people from both southeast Alaska and the state’s northern edge.

“There’s 1,000 miles in between those two communities, and they were able to come to the same meeting,” she says. “So we were getting perspectives from people that we traditionally have not heard from before.”

BLM says the eight sessions had about 300 unique attendees, plus another 2,000 on Facebook Live, far more people than had attended community meetings before the pandemic.

In March, federal agencies also canceled hearings on a proposal to remove dams to help threatened salmon in the Columbia River Basin. Thirteen members of Congress from the Pacific Northwest asked to extend the comment period.

“The current crisis cannot plausibly provide for an environment conducive to robust public comment,” they wrote.

The request was not granted, and the comment period is now closed.

The Trump administration has also moved ahead with changes that affect state water pollution permits and liquefied natural gas development, in addition to relaxing the Obama-era rules on fuel efficiency and pollution in streams and wetlands.

Sharlett Mena, special assistant to the director of the Washington Department of Ecology, says all this undermines state environmental protections for air and water.

“All of these rules have gone forth with our very vocal objection,” she says. “And they were finalized now, when we’re flat-footed and we’re worried about our communities. We’re worried about recovery.”

“So much going on in the world”

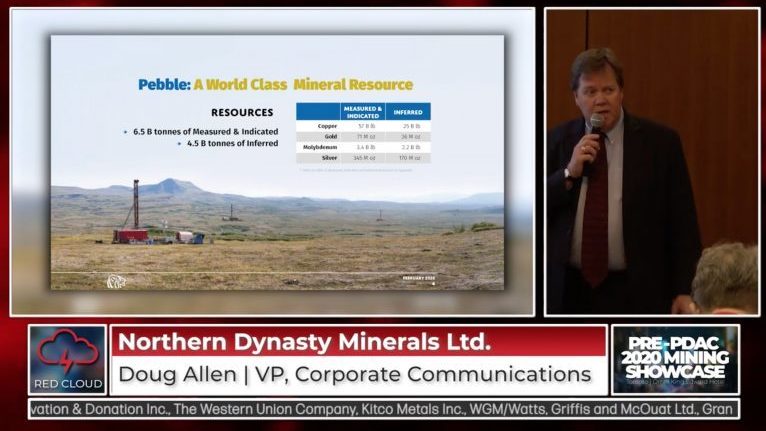

Lindsey Bloom thought she finally had the goods to oppose development of Alaska’s Pebble Mine. The Obama administration had blocked the gold and copper mine, saying it would threaten the nation’s most valuable salmon fishery, but the Trump administration reversed that.

Bloom discovered a video from a conference in late February, when an executive from Pebble’s parent company pitched investors. She considered it proof of what fishermen and environmental groups have been warning – that Pebble is minimizing the scope of its plans.

“One of the ways you ensure you can get a permit is you de-risk it by taking something modest and conservative into the permitting process in the first place. And we did that,” Northern Dynasty Vice President Doug Allen says on the video. He went on to say the company expects to get a permit to extract more gold at a later date.

Northern Dynasty Vice President Doug Allen pitched the Pebble Mine to potential investors February 28, 2020. Image via YouTube

Bloom, who works for Commercial Fishermen for Bristol Bay, sent a transcript of the comments to multiple news outlets, expecting to generate headlines. But “I haven’t been hearing anything back from reporters,” she says. “The airwaves are so crowded right now. So much going on in the world.”

Pebble spokesman Mike Heatwole declined to be interviewed, but pointed out in an email that the public input period on the mine ended last year.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is now in the final phase, working with government agencies and tribes before it decides on issuing permits. One of those select agencies is supposed to be the Curyung Tribe, but its leaders say they can’t keep up with the Pebble documents or attend the biweekly agency meetings.

“All of our tribal focus right now has become COVID and maintaining the health and safety of our people here in Bristol Bay,” says administrator Courtenay Carty.

Thousands of workers are heading to the area for the annual salmon fishery despite concerns about a possible outbreak of COVID-19.

“We’re really disenfranchised at this point in time,” Carty says. “To (not) be able to focus on something as important as the Pebble permitting process, that we’ve dedicated over a decade to, to have it come to decision essentially over summer in the midst of a global pandemic, is unfathomable.”

Last month, Pebble changed its preferred transportation route for getting the gold out, prompting more criticism that interested parties are not able to adequately respond.

Pushing through rollbacks while easing enforcement

At a recent Senate hearing, Environmental Protection Agency administrator Andrew Wheeler defended the flurry of action during the pandemic. “EPA employees have risen to the test of carrying out their duties during this challenging time, and I applaud all of them,” Wheeler said.

But Democratic Senators criticized Wheeler for making changes that could worsen air pollution, even as the nation grapples with a pandemic from a respiratory disease.

They also questioned his agency’s move to relax compliance and monitoring of clean air and water laws during the crisis. Nine states and a dozen environmental groups have sued EPA over the measure, alleging it gives polluters too much leeway.

Wheeler countered that EPA is still carrying out enforcement. And the agency said in a statement that there is “no leniency for those who exhibit an intentional disregard for the law or for accidental releases of oil, hazardous substances, hazardous chemicals, hazardous waste or other pollutants.”

Still, the move rankles Brett VandenHeuvel, Executive Director of Columbia Riverkeeper in Oregon.

“We’re seeing simultaneously that they can’t do their jobs to enforce environmental laws, but they can push forward dirty pollution-causing projects,” he says.

Environmental regulators in Oregon and Washington State say easing federal compliance puts more of the onus on them to make sure industrial facilities are operating properly, even as their own agency budgets are collapsing because of the pandemic’s economic fallout.

But states are still challenging the administration’s rollbacks, most recently with a lawsuit against weaker standards for fuel efficiency in cars and trucks.

Oregon Department of Environmental Quality Director Richard Whitman calls the rule “ill-advised” and says it would set back his state’s climate goals to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from transportation.

“In my mind, this is really about propping up our petroleum industry,” Whitman says. Doing that “in the middle of the pandemic, I will say, grates on us.”

This story is a collaboration with Oregon Public Broadcasting and Alaska Public Media.