Jimmy Cobb, The Pulse Of Miles Davis’ ‘Kind Of Blue,’ Dies At 91

BY NATALIE WEINER

Jimmy Cobb, whose subtle and steady drumming formed the pulse of some of jazz’s most beloved recordings, died at his home in Manhattan on Sunday. He was 91.

The cause was lung cancer, says his wife, Eleana Tee Cobb.

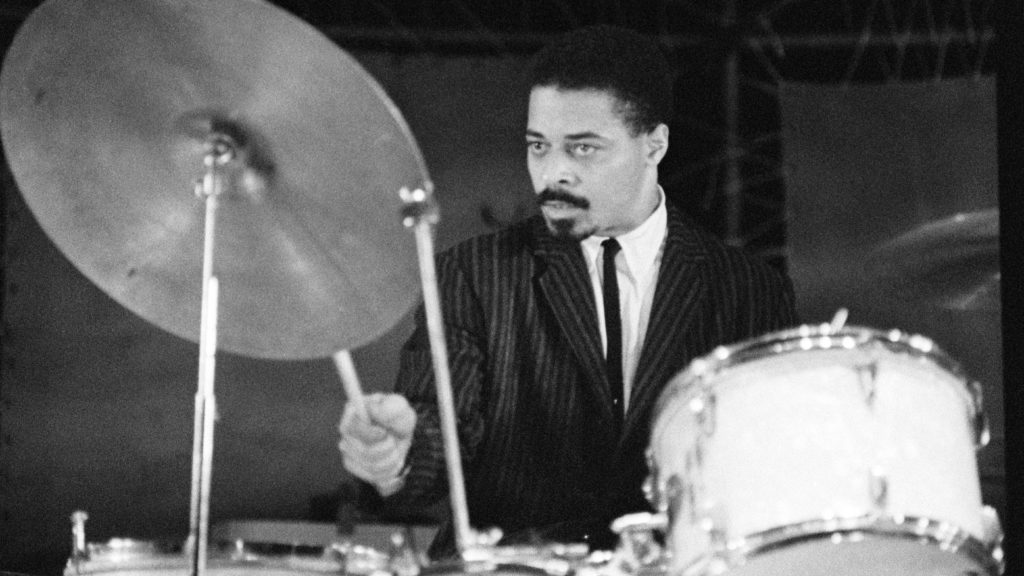

Jimmy Cobb was the last surviving member of what’s often called Miles Davis’ First Great Sextet.

CREDIT: Gai Terrell/Redferns

Cobb was the last surviving member of what’s often called Miles Davis’ First Great Sextet. He held that title for almost three decades, serving as a conduit for many generations of jazz fans into the band that recorded the music’s most iconic and enduring album, Kind of Blue.

It’s impossible to overstate how much his playing, which propelled that all-star group forward with delicate washes of cymbals and brush-stroked snare, contributed to Kind of Blue‘s undeniable bounce and feel. “Jimmy, you know what to do,” Davis told Cobb before the session. “Just make it sound like it’s floating.” And it does: The perfect tension between Cobb’s signature driving cymbal beat and Paul Chambers’ relaxed walking bassline makes most people’s first jazz album one that you can — or can’t help but — move to.

Cobb’s strength was always understatement, which meant that he didn’t necessarily get the same accolades and attention as some of his peers behind the kit. But his simplicity and intuitive feel made Cobb’s grooves a seamless part of any band’s living organism, its backbone or heartbeat.

Along with playing on other canonical Davis albums like Sketches of Spain and In Person Friday and Saturday Nights at the Blackhawk, Cobb helped crystallize the straightforward swing that brought hard bop to its greatest heights. He and his Davis bandmates Paul Chambers and pianist Wynton Kelly continued to play together — as a trio under Kelly’s name, and as a prolific rhythm team — until Chambers’ untimely death in 1969. They collaborated with Cannonball Adderley, John Coltrane, Wayne Shorter, Benny Golson, Wes Montgomery, Hank Mobley, Art Pepper and Joe Henderson.

Cobb’s willingness to play a supporting role — as well as his unmatched ability to find the beauty in the background — meant that some of his longest tenures were as an accompanist to legendary vocalists Dinah Washington and Sarah Vaughan. He often cited that experience as formative. “I guess the sensitivity probably comes from having to work with singers, because you have to really be sensitive there,” he said in an oral history by the Smithsonian, when he was named an NEA Jazz Master in 2009. “You have to listen and just be a part of what’s going on.”

Born James Wilbur Cobb on Jan. 20, 1929, Cobb had longed to be part of what was going on since his teens, when he stayed up to listen to Symphony Sid’s late-night broadcast and worked as a busboy at a lunch counter in northwest Washington, D.C. Eventually he saved up enough money to buy a drum set, and started gigging professionally soon thereafter. For him, the “why” was straightforward. “I figured it was something I’d like to do,” said Cobb, “and when I learned enough to do it, I figured that would be what I would do for the rest of my life.”

Before his 20th birthday, the young drummer, who modeled himself after Max Roach and Kenny Clarke, was already getting high-profile gigs. Cobb played with Billie Holiday during a stint in D.C., and eventually in Symphony Sid’s traveling show, where he spent a week alongside Charlie Parker and Miles Davis — making him one of the last musicians able to say that they’d played with Bird and Lady Day.

Cobb never shied from his status as a living link to the music’s venerable past, instead emphasizing what he viewed as a lifetime of good luck. “I’ve been in the right place at the right time a lot of times,” he said. “[But today] things are more mechanical than human, than they used to be. [Students today] got some advantages, because they have videos and all that, but it’s not walking up and shaking the dude’s hand and talking about things, or asking him questions.”

His first traveling gig with saxophonist Earl Bostic quickly turned into five years with Bostic’s tourmate Dinah Washington — which also happened to be the first of 20 years of collaborations with her then-pianist, Wynton Kelly. Cobb is featured on many of Washington’s most memorable recordings, including the underrated For Those In Love, for which a very young Quincy Jones provided the arrangements.

From there, he was recruited by Cannonball Adderley to play on some of that saxophonist’s earliest records — and eventually to join Adderley in Miles’ band. Kind of Blue was recorded shortly after Cobb’s 30th birthday. He was paid scale (something like $100 for all the album’s sessions), and never received any royalties.

Despite the tireless work required of a sideman just to make ends meet, Cobb didn’t record as a bandleader until the early 1980s. By the ’90s, he was beginning to mentor young musicians in much the same way he had been in his early days — Roy Hargrove, Christian McBride, Wallace Roney and particularly Brad Mehldau, who played in the first edition of his band Cobb’s Mob while still in Cobb’s class at the New School, were all recorded to the beat of his evergreen swing.

“As a drummer, he makes you feel so comfortable,” guitarist Peter Bernstein — another one of Cobb’s former students — said in the liner notes for This I Dig Of You, released last year. “Like, this is what it’s supposed to feel like.”

Cobb continued to perform and teach around the globe up until the end of his life. His family — his wife, Eleana Steinberg Cobb, and two daughters Serena and Jaime, all of whom survive him — organized most of his playing and teaching as he got older. Students never stopped asking how to master that light, insistent cymbal — something he made sound so easy, yet they quickly realized couldn’t be harder. But there was no secret, according to Cobb. “The first thing is they have to love it, and stay with it,” he said.

He lived that maxim, playing perfect time in countless bands, making music that he thankfully lived long enough to learn was timeless. When people decide to start listening to jazz today, one of the first people they hear is Jimmy Cobb, floating.

Nate Chinen of WBGO contributed to this story.