Most Americans Think It Will Be At Least 6 Months Before A Return To Normal From COVID-19

READ ON

BY LAURA SANTHANAM / PBS NewsHour

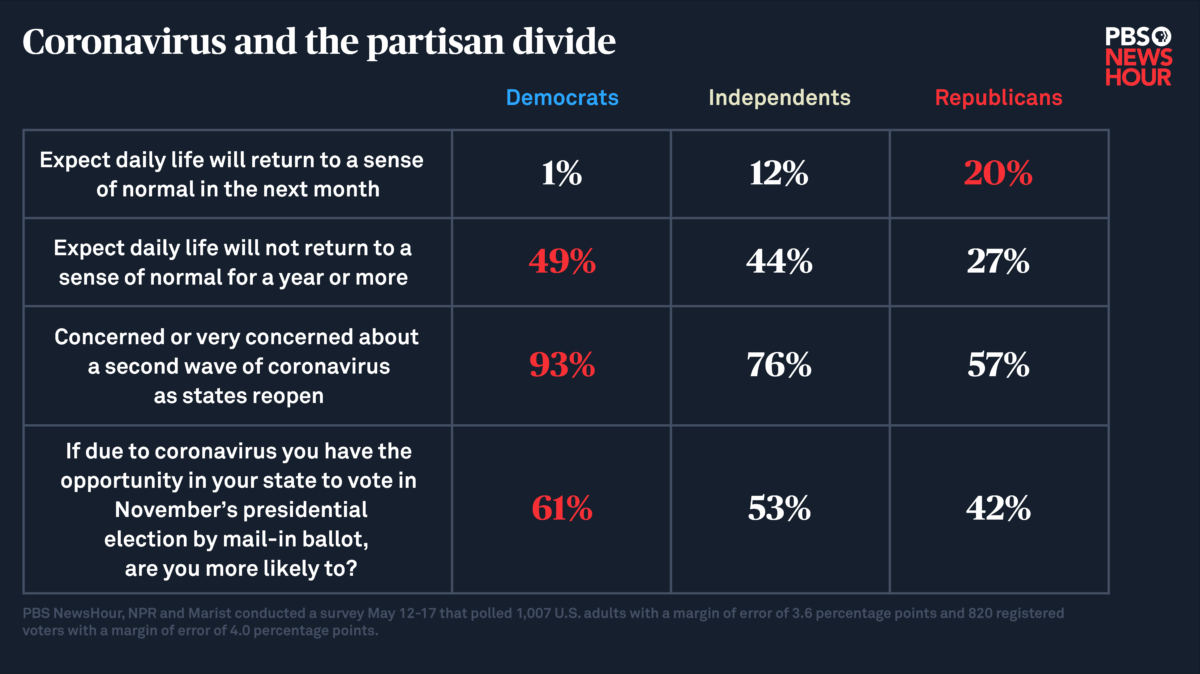

Most Americans think it will take six months or longer for daily life to return to a relative sense of normal, according to a new PBS NewsHour/NPR/Marist poll. And as states begin the process of reopening, a majority of Americans are worried about a second wave of COVID-19 infections, too.

The poll also found that, if given the opportunity to avoid their polling place and instead cast a mail-in ballot for November’s presidential election, half of Americans would likely do so.

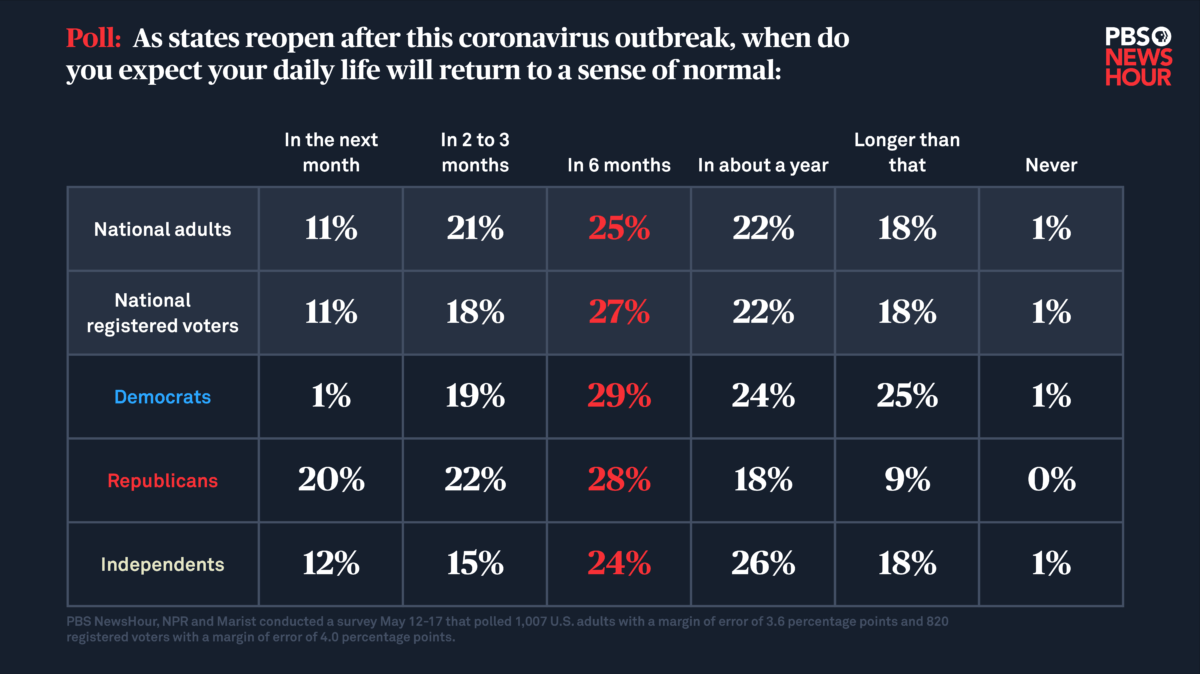

Republicans were far more optimistic about the country’s resilience than American adults overall, according to this latest poll, while Democrats were more pessimistic. Eleven percent of U.S. adults think the nation will be back to normal in a month, including 20 percent of Republicans, 1 percent of Democrats and 12 percent of independents.

Nearly a third of Americans think it will take the country less than six months to resume a relatively normal pace of life, but a majority of Americans — 65 percent — think it will be six months or longer to return to a sense of normal. One percent of U.S. adults don’t think their daily lives will ever return to normal, while another 1 percent believe they already have. An additional 1 percent never felt a change.

Getting back to normal

For weeks, states have been relaxing social distancing restrictions to revive the economy, with Georgia, Texas and Florida among the earliest to reopen. During the months since the pandemic started, the United States has lost nearly 40 million jobs, eliminating employment gains made since the Great Recession. As nearly every state enters various phases of reopening, the country is “in a toe-dipping situation,” said Michael Chernew, a health economist and a professor of health care policy at Harvard Medical School.

“People are limited by their caution, not just by the restrictions,” he said. “Even if there’s a minority of people who feel we should be getting back to normal, it’s hard to get back to normal when a significant portion of the people don’t feel that way.”

“It’s hard to get back to normal when a significant portion of the people don’t feel that way.”

Michael R. Strain, who directs economic policy studies at the American Enterprise Institute, said he was “shocked” by how divergently Democrats and Republicans viewed the nation’s reopening, especially given how differently parts of the country have experienced coronavirus.

“I expected that party affiliation would be the biggest difference, but it is so much bigger than region,” Strain said.

Risk of a second wave

While the coronavirus is continuing its sweep of the United States, most Americans are already bracing for a second wave of infections. More than three-quarters of U.S. adults — 77 percent — are concerned about another round of infections, while 23 percent of Americans are not.

That concern was sharply divided along party lines, with 93 percent of Democrats and 76 percent of independents saying they were nervous about another increase in infections. Republicans were more evenly split, with 57 percent saying they were concerned about a second wave and 43 percent saying they were not very concerned or not at all concerned.

So far, COVID-19 has killed more than 86,000 Americans, and more than 1.5 million have tested positive for the virus, according to the COVID Tracking Project. Nearly 290,000 additional Americans have recovered after getting sick. No vaccine or medication has completed trials nor been approved to treat or prevent COVID-19.

Researchers at the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, who developed computer modeling to project the virus’ spread, have suggested new infections could begin to dwindle by June, but those estimates can change rapidly. Public health officials have cautioned that if the U.S. reopens too quickly or does not have adequate testing or contact tracing to monitor for new outbreaks, waves of new infections will occur.

President Donald Trump acknowledged on a recent trip to Phoenix that some people will be “affected badly” as restrictions are lifted, but that “we have to get our country open and we have to get it open soon.”

But Americans have been apprehensive about trying to return to normal before the country is ready. A PBS NewsHour/NPR/Marist poll from April 29 found that a majority of U.S. adults were not comfortable sending children back to school, allowing people to dine inside restaurants or allowing large gatherings for sporting events until COVID-19 testing improved.

And public health experts say testing is still far from where it should be. Currently, roughly 300,000 tests are administered across the country each day. Many estimates suggest those numbers need to be far greater to adequately measure the rate of infection and monitor the virus’ spread. One analysis from the Harvard Global Health Institute said the U.S. needed to test at least 900,000 people daily by May 15.

“Our initial response to the pandemic has been wholly inadequate,” said Dr. Ashish Jha, the institute’s director, who testified before Congress on May 13 about the state of testing.

How might the pandemic affect the 2020 presidential election?

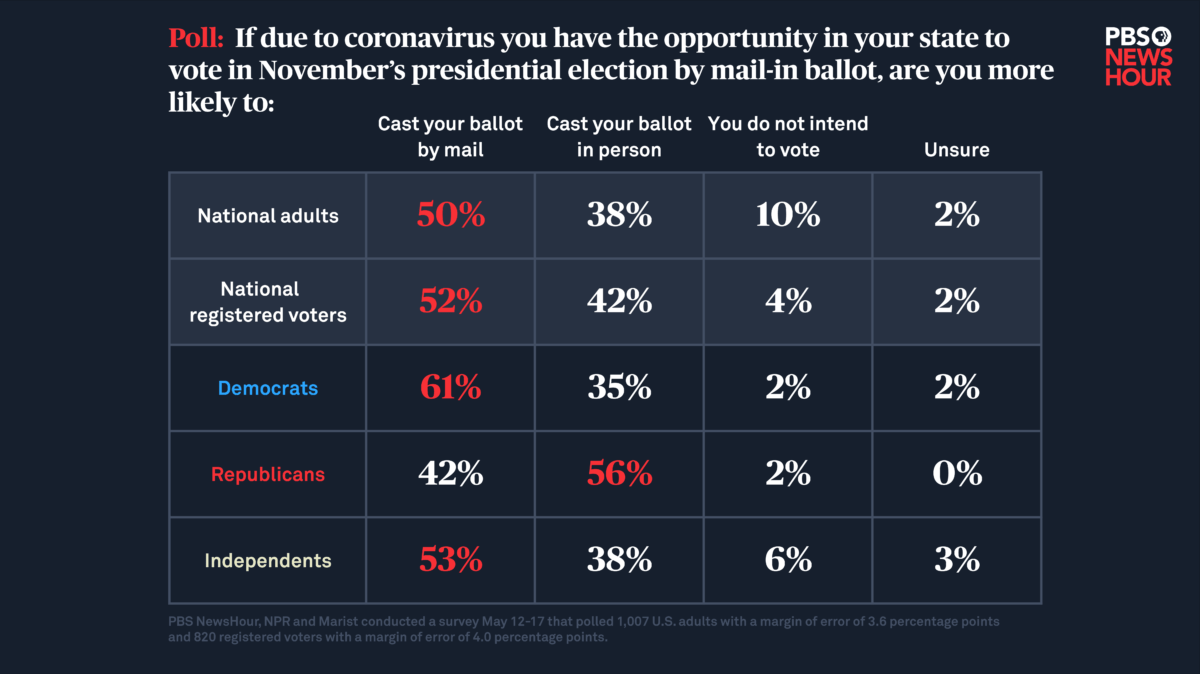

Half of Americans would likely cast a mail-in ballot for November’s presidential election if given the opportunity due to coronavirus. Another 38 percent would still likely vote in person, and 10 percent do not intend to vote.

People under the age of 45, especially those between ages 18 and 38, were more likely to say they would skip voting, as were non-white individuals and white Americans who did not graduate from college.

Studies suggest American voters are guilty of overstating their participation in democracy. In a 2010 study in Public Opinion Quarterly, researchers stated that social desirability — an urge to please others — drove many Americans to say they voted or planned to do so but then failed to follow through.

In the 2016 presidential election, nearly 137 million Americans cast a ballot. During that election, roughly a quarter of voters mailed in their ballots, said Lee Miringoff, who directs the Marist Institute for Public Opinion.

Before the pandemic, advocates of mail-in voting said it would enable more people to participate.

California, Colorado, Hawaii, Oregon, Utah and Washington automatically send registered voters their ballots by mail, according to the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University’s School of Law, while 28 more states and the District of Columbia allow all voters to vote by mail without an excuse. Other states offer absentee voting only under certain conditions.

Some states took special steps to expand mail-in voting for primaries, and others are considering changes ahead of the general election.

The influence of COVID-19 on the American electoral process may have already played out in one state’s primary, said Michael Waldman, president of the Brennan Center.

Wisconsin held local elections and its Democratic presidential primary April 7. Amid concerns about the spread of COVID-19, many voters were confronted with choosing between going to the polls and risking exposure, or sitting out the election, after the state’s Republican-led legislature did not delay the election or further expand Wisconsin’s mail-in voting. While the state offered mail-in voting, the system buckled under demand that in a week’s time rose from 250,000 ballots to more than 1.5 million, Waldman said.

Weeks after the primary, the number of confirmed cases of COVID-19 rose, and the Wisconsin Department of Health Services used detailed contact tracing to link more than 50 new cases to polling stations, said Erik Nesson, an economist at Ball State University and one of the authors of a preliminary report for the National Bureau of Economic Research on the role the virus played in the Wisconsin election.

Nesson and his colleagues found that “Wisconsin counties with higher levels of in-person voting per polling location led to increases in the weekly positive rate of COVID-19 tests,” according to their report.

On the same day as the Wisconsin primaries, Trump criticized voting by mail, characterizing the process as fraudulent. Historically, little evidence has supported this claim. In 2014, Loyola Law School Professor Justin Levitt wrote in the Washington Post that he found 31 examples of possible voter fraud among 1 billion ballots cast between 2000 and 2014.

Since then, Trump has continued to target mail-in ballots. On Wednesday, he tweeted: “State of Nevada ‘thinks’ that they can send out illegal vote by mail ballots, creating a great Voter Fraud scenario for the State and the U.S. They can’t! If they do, ‘I think’ I can hold up funds to the State. Sorry, but you must not cheat in elections.”

During this election cycle, Waldman said several states have reported spikes in voting by mail, and that support has come from Democrats, Republicans and independents. But Wisconsin, he said, should serve as a cautionary tale for this fall.

“People had to choose between their health and their right to vote in a really unnerving situation,” he said. “We could have a lot of Wisconsins in November if something doesn’t happen.”

PBS NewsHour, NPR and Marist conducted a survey May 12-17 that polled 1,007 U.S. adults with a margin of error of 3.6 percentage points and 820 registered voters with a margin of error of 4.0 percentage points.

Copyright 2020 PBS NewsHour. To see more, visit pbs.org/newshour.

Related Stories:

COVID-19, 5 years later: Reflections on the scars we carry, and resilience in unprecedented times

NWPB caught up with local residents and doctors to talk about how they’ve moved forward following the COVID-19 pandemic. They spoke about how the experience changed them and wisdom they’ve gleaned along the way. These are their reflections.

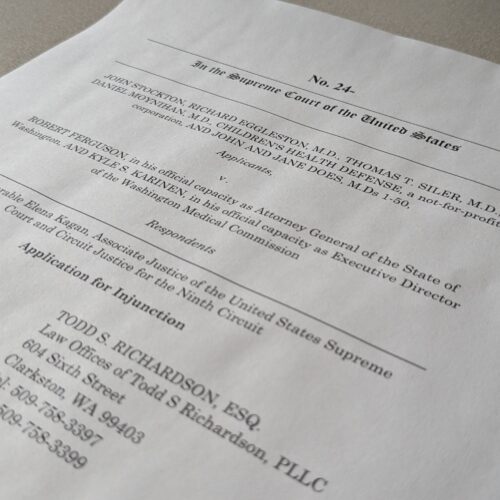

US Supreme Court will consider petition for stay in COVID-19 free speech case

The U.S. Supreme Court will review an application for a stay in a federal lawsuit involving local retired eye doctor Richard Eggleston.

Group representing retired Clarkston ophthalmologist asks US Supreme Court for injunctive relief

A retired Clarkston eye doctor is part of a group asking the U-S Supreme Court to grant an injunction in a lawsuit against Washington state officials.