40 Years After Mount St. Helens, Sounds Of Past Government Response Echo Today

Listen

In the days leading up to the May 18, 1980 Mount St. Helens eruption 40 years ago, Cowlitz County sheriff’s deputies tried to prevent people from getting too close to the growling, shaking mountain.

Not everyone listened, and public pressure grew great enough for law enforcement to relent. The day before the volcano blew and killed 57 people — making it the most fatal natural disaster in modern Washington state history — deputies let people go to their cabins around Spirit Lake.

Most left by an evening deadline. But in the eruption’s aftermath, people pointed fingers, especially at Gov. Dixy Lee Ray.

Dixy Lee Ray was Washington’s governor during the lead-up to and immediate aftermath of the Mount St. Helens eruption in 1980. CREDIT: Harold “Scotty” Sapiro / Washington State Archives

Ray, who had a doctorate in biology from Stanford University and had already been chair of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, declared a state of emergency before the blast, and warned people that the “possibility of a major eruption or mudflow is real.”

Beyond that, she believed people should just use good sense and stay away from the mountain. She didn’t believe it was possible or appropriate for the government to prevent people from getting too close.

Ray failed in her re-election bid that year, having lost the Democratic Party’s nomination to Jim McDermott. Two years later, she defended her actions in a public TV documentary titled, “Why They Died.”

“And it’s easy now for people to say, ‘After the eruption took place, and there was some loss of life, you should’ve done it different. You shouldn’t have let me go in there. You should’ve prevented it. You should’ve put an army there, if necessary to keep us out,’” Ray said at the time.“That’s all just hindsight. Because the fact is, we undertake and accept risks every single day. And there are a lot of things that we do that are far more risky than what the probability is of an eruption of Mount St. Helens.”

Four decades later, President Donald Trump said things similar to Ray in his defense of how he’s handled the coronavirus outbreak.

“Nobody knew there’d be a pandemic or an epidemic of this proportion,” he said March 19.

Trump has also grafted the cold calculus of the risk we accept every time we get in a car, as well as the deadliness of the seasonal flu, onto the odds of fatality in a viral outbreak.

“We lose thousands of people a year to the flu. We never turn the country off,” Trump said in late March from the White House Rose Garden as he urged the easing of stay-home orders across the country. “We lose much more than that to automobile accidents. We didn’t call up the automobile companies and say, ‘Stop making cars.’”

But scientists who have studied the mountain are taking away different lessons from the eruption of Mount St. Helens and how it may inform today’s public health emergency.

Eric Wagner, who recently published a book on St. Helens’ ecology, said there are “disaster parallels.”

“People just didn’t take it seriously in the run up,” Wagner said of the eruption. “They thought it would just be interesting and this funny thing. And the government response was kind of muddled. There were eviction orders that were ignored. People like Harry Truman were famous for ignoring them.”

Truman ran the Mount St. Helens Lodge at Spirit Lake. He became something of a folk hero in the months before the eruption for flouting orders to leave. He died in the eruption.

The survivor experience, however, may have more to tell us.

“To think of it from the standpoint of living through trauma. To remind yourself that you have survived,” he said. “You like to think that things will go back to the way they are, but disturbance and disaster tells you that they probably won’t.”

Seth Moran, scientist-in-charge at the U.S. Geological Survey’s Cascades Volcano Observatory, said he views the eruption and pandemic as powerful natural events that most of us have or will survive and remember.

“Nature is endlessly fascinating, and we live in it,” Moran said. “Every so often, something happens that is beyond anything we’ve ever experienced before and illustrates the tremendous power and energy of natural processes at the time. That includes whiz bangers of thunderstorms and tornadoes and hurricanes. For people who have lived through those, those are all things that get seared in your brain and you talk about them for forever afterwards.”

Fred Swanson is a research geologist who has spent his career studying volcanoes, especially St. Helens. He went to the mountain as an undergraduate student, and kept an eye on it during his career with the U.S. Forest Service. He continues to visit and study volcanoes in Chile.

While he’s become especially concerned with global climate change, he says science gives reason to have faith.

“As a geologist, whether it’s in a volcanic eruption case, pandemic case, especially climate change case, we need to take the long view,” Swanson said. “We need to be smart and attentive and take proximal precautions, such as being aware of volcano history and not putting ourselves in harms’ way. But also have faith that we’ll get out of this. In some ways, the world may not be the same.”

Related Stories:

On Mount St. Helens, students dig into potential geology careers

Elise Cha, left, and Kellee Kendrick, right, learn about the viscosity of magma by pouring corn syrup on cookie sheets. (Credit: Courtney Flatt / NWPB) Watch Listen (Runtime 4:14) Read

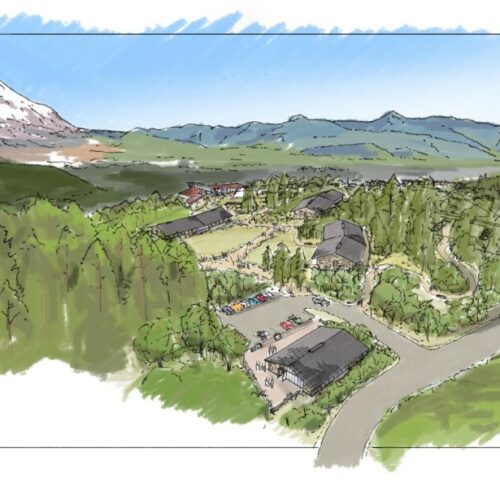

Volcano Lodge And Developed Campground Okayed In Mount St. Helens National Monument

The U.S. Forest Service has okayed a plan to develop what would be the first overnight tourist facilities within the Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument, including camping, cabins and a lodge.

A Road Across Mount St. Helens Blast Zone Threatens One-Of-A-Kind Research, Lawsuit Says

Conservation groups and scientists are challenging a federal decision to build a road through the Mount St. Helens blast zone, saying it would damage more than two dozen decades worth of irreplaceable research plots.